Inuit phonology facts for kids

The Inuit languages are spoken by Inuit people across the Arctic. This article explains how sounds work in these languages, focusing mostly on the Inuktitut dialects spoken in Canada.

Most Inuit languages have fifteen consonant sounds and three main vowel sounds. Each vowel can be short or long, which changes the meaning of words. For example, a long 'a' sound is different from a short 'a' sound. Some older dialects, like Iñupiaq in Alaska, used to have more sounds, but many of these have changed over time in other dialects.

Contents

Vowels: Short and Long Sounds

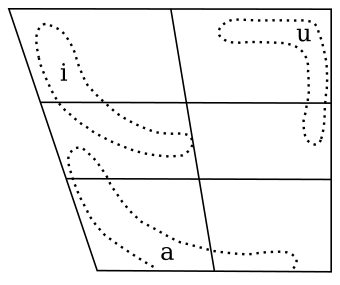

Almost all Inuktitut dialects have three basic vowel sounds: 'a', 'i', and 'u'. What's special is that each of these can be pronounced as a short sound or a long sound. This length difference is important because it can change the meaning of a word!

In Inuujingajut, which is the standard way of writing Inuktitut in Nunavut, long vowels are written by doubling the letter.

| Sound (IPA) | How it's written in Inuujingajut |

|---|---|

| /a/ | a (short 'a' sound) |

| /aː/ | aa (long 'a' sound) |

| /i/ | i (short 'i' sound) |

| /iː/ | ii (long 'i' sound) |

| /u/ | u (short 'u' sound) |

| /uː/ | uu (long 'u' sound) |

In some parts of western Alaska, like the Qawiaraq dialect, there used to be an extra vowel sound, similar to the 'e' in "the". This sound has mostly changed to 'i' or 'a' in other dialects. For example, the word for water, imiq in most Inuktitut dialects, is emeq in Qawiaraq.

Also, in some Alaskan dialects, certain diphthongs (two vowel sounds blended together, like 'oy' in "boy") have merged into single sounds. This means they are starting to have more complex vowel systems.

On the other hand, in northwest Greenland, the 'u' sound has sometimes changed to an 'i' sound in many words. But generally, the three-vowel system (a, i, u, each short or long) is found across most Inuktitut dialects.

Consonants: The Building Blocks of Words

The Inuktitut dialects in Nunavut usually have fifteen different consonant sounds. Some dialects might have a few more.

The table below shows the different consonant sounds. Don't worry too much about the technical names, but it's cool to see how sounds are made using different parts of your mouth!

| Lip sounds | Tongue-tip sounds | Curled-tongue sounds | Mid-tongue sounds | Back-tongue sounds | Throat sounds | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| middle | side | |||||||

| Nasal sounds | m (like 'm' in 'mom') | n (like 'n' in 'no') | ŋ (like 'ng' in 'sing') | |||||

| Stop sounds | no voice | p (like 'p' in 'pat') | t (like 't' in 'top') | k (like 'k' in 'kit') | q (like 'k' but further back in throat) | |||

| with voice | ɟ (like 'j' in 'jam', only in some dialects) | ɡ (like 'g' in 'go') | ||||||

| Continuant sounds | no voice | s (like 's' in 'sit') | ɬ (like 'thl' in 'athlete') | ʂ (like 'sh' but with curled tongue, only in some dialects) | ||||

| with voice | v (like 'v' in 'van') | l (like 'l' in 'lap') | ʐ (like 'zh' but with curled tongue, only in some dialects) | j (like 'y' in 'yes') | (ɣ) (like 'g' but softer, in some dialects) | ʁ (like 'r' but in throat, can sound like 'n' before some sounds) | ||

Stress: Where the Emphasis Goes

In Inuktitut, the main emphasis or "stress" in a word usually falls on the very last part (syllable) of the word.

Intonation: The Music of Speech

Intonation is the way your voice rises and falls when you speak. In Inuktitut, intonation is important for telling some words apart, especially questions. Even though it's not usually written down, it helps you understand the meaning.

For example, the word suva can mean two different things depending on your voice:

- If you say suva with a high pitch on the first part and a falling pitch on the second, it means "What did you say?"

- If you say suva with a middle pitch on the first part and a rising pitch on the second, it means "What did he do?"

Just like in English, Inuktitut uses intonation for questions. If a question word like "who" or "what" is used, your voice usually falls at the end. If there's no question word, your voice rises on the last syllable.

Sometimes, Inuktitut speakers will make vowels longer when their voice rises. So, a rising tone might be shown by writing a double vowel:

| She can speak Inuktitut. | Inuktitut uqaqtuq. | |

| Does she speak Inuktitut? | Inuktitut uqaqtuuq? |

How Sounds Fit Together (Phonotactics)

Inuktitut has rules about how sounds can be put together in a syllable (a part of a word, like 'cat' has one syllable). A syllable can only have one consonant at the beginning and one at the end. This means that groups of consonants, like 'st' or 'pl', are usually simplified or changed if they appear.

When different word parts (morphemes) are joined, two consonants might come together. But three consonants together are always simplified. Also, consonants are grouped by how they are made:

| Voiceless sounds (no voice box vibration): | p t k q s ɬ | |

|---|---|---|

| Voiced sounds (voice box vibrates): | v l j ɡ ʁ | |

| Nasal sounds (air through nose): | m n ŋ |

When two consonants come together, they usually need to be from the same group. If they are from different groups, they often change to become more alike. This is called assimilation. For example, one sound might become exactly like the other, or it might take on some features of the other sound. This is why words can sound different in various dialects.

For instance, the word for 'you (singular)' changes quite a bit across dialects:

| Dialect | word |

|---|---|

| Inupiatun | ilvich |

| Siglitun | ilvit |

| Inuinnaqtun | ilvit |

| North Baffin | ivvit |

| South Baffin/Nunavik | ivvit |

| Kalaallisut (Greenlandic) | illit |

Another example is the word for 'house':

| English | Inupiatun | Inuinnaqtun | South Baffin | Kalaallisut |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| house | iglu | iglu | illu | illu |

These changes show how sounds adapt to each other when they are next to each other in a word.

Other Dialect Differences

Consonant Weakening in Qawiaraq

In the Qawiaraq dialect of Alaska, some consonant sounds have become "weaker." This means that stop sounds (like 'p' or 't') might become fricative sounds (like 'f' or 's'), and fricative sounds might become even softer or disappear. For example, the word for meat, which is niqi in most dialects, is nigi in Qawiaraq. Here, the 'q' sound has become a softer 'g' sound.

Palatalization in Inupiatun

In the Inupiatun dialect, some sounds change when they follow an 'i' vowel. This is called palatalization, where the sound is made with the middle of the tongue closer to the roof of the mouth. For example, the 't' sound can become a 'ch' sound. The word for you (singular), ilvit in many dialects, becomes ilvich in Inupiatun.

| Original sound | Palatalized sound | Inupiatun spelling | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| /t/ | /tʃ/ (like 'ch') | ch | ilvit → ilvich (you [sg.]) |

| /n/ | /ɲ/ (like 'ny' in 'canyon') | ñ | inuk → iñuk (person) |

| /l/ | /ʎ/ (like 'ly' in 'million') | ḷ | silami → siḷami (outside) |

In some western and central dialects of Nunavut, like Inuinnaqtun, the 's' sound is often pronounced as an 'h' sound. So, a word that might have an 's' in other dialects will have an 'h' instead.

| English | Inuinnaqtun | Kivallirmiutut | North Baffin |

|---|---|---|---|

| egg | ikhi | ikhi | iksi |

| blubber | uqhuq | uqhuq | uqsuq |

Retroflex Consonants in Western Dialects

Some western dialects, like Natsilingmiutut and Inupiatun, have special sounds called retroflex consonants. These are made by curling the tongue back in the mouth. For example, the 'j' sound in Natsilingmiutut can be a retroflex sound. In Inupiatun, some 'j' sounds become an 'r' sound made by curling the tongue.

| English | Inupiatun | Natsilingmiutut | North Baffin | Kalaallisut |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| eye | iri | iri | iji | isi |

| kayak | qayaq | qajaq | qajaq | qajaq |

| big | angiruq | angiruq | angijuq | angivoq |

Glottal Stops

In some dialects, certain sounds made in the back of the throat (like 'q') can be replaced by a glottal stop. A glottal stop is the sound you make in the middle of "uh-oh" – it's a quick closing of your throat. For example, the name of Baker Lake is usually Qamaniqtuaq, but in Baker Lake itself, it's pronounced Qamani'tuaq, with a glottal stop. This happens a lot in Nunavik and central Nunavut dialects.

|

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |