Inundation of Walcheren facts for kids

The Inundation of Walcheren was when the Allies (the countries fighting against Germany in World War II) intentionally flooded the former island of Walcheren in Zeeland, Netherlands. This happened by bombing the sea dikes starting on October 3, 1944. It was part of a bigger plan called Operation Infatuate during the Battle of the Scheldt.

The flooding was done for military reasons, to help win the war. However, it caused huge damage to the island and its people. The dikes stayed broken for a very long time, until October 1945. This meant the island was flooded twice a day by the tides, which ruined farms and buildings. Fixing the dikes was very difficult and required new building methods. The island was finally dry in early 1946, and rebuilding began. Interestingly, Walcheren was safe during the big North Sea Flood of 1953 that hit other parts of Zeeland.

Contents

Why Walcheren Was Flooded

In September 1944, the Allied armies were moving very fast. But they had a problem: their supplies from the temporary ports in Normandy were running out because the supply lines were too long. They needed a closer, bigger port.

The port of Antwerp in Belgium was perfect, and the Allies had captured it. However, German soldiers still controlled the banks of the Scheldt River, which led to Antwerp. This meant ships couldn't get through. The island of Walcheren, at the mouth of the Western Scheldt, was like a strong fortress. It had powerful German coastal guns that blocked the sea route. These guns also made it impossible to clear the German naval mines in the shipping channel. So, taking Walcheren was absolutely necessary for the Allies to use Antwerp port.

Planning the Attack

The job of taking Walcheren was given to the First Canadian Army. Their planning started in September 1944. At first, they thought about a ground attack across a causeway (a raised road over water) and even dropping paratroopers. But the paratrooper idea was dropped because many airborne forces were already busy with another big operation.

General Guy Simonds, who led the Canadian army, then suggested flooding the island. He wanted the RAF Bomber Command to bomb the dikes and "completely flood all parts of the island below high water level." He hoped this would break the German soldiers' spirits and make their defenses useless.

Not everyone agreed with this plan. Some thought bombing the dikes wouldn't be enough to flood the island. Others believed flooding would make it harder for the attackers, especially tanks, to move around. Despite these concerns, the top Allied commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, approved the idea on October 1, 1944. He later said the breaches in the dikes were "of great usefulness." It's worth noting that the Dutch government-in-exile was not asked for their opinion, even though they were worried about the plan.

Breaking the Sea Walls

The bombing of the dikes began on October 3, 1944. RAF Bomber Command attacked the sea dike near Westkapelle, dropping many bombs. This broke the dike and sadly killed 152 civilians. The Royal Air Force had dropped warnings the day before, telling people to leave, but many had nowhere to go.

As some engineers had predicted, this one breach wasn't enough to flood the whole island. So, on October 7, more RAF bombers attacked other dikes near Vlissingen and Ritthem. This still wasn't enough. On October 11, the dike between Veere and Vrouwenpolder on the north coast was also bombed and broken. A second bombing of the Westkapelle breach happened on October 17.

Military Operations on the Flooded Island

While the water slowly spread across Walcheren, the RAF also bombed German artillery positions. These strong bunkers were hard to destroy, though some were hit by chance. These bombings also killed civilians in places like Biggekerke and Vlissingen.

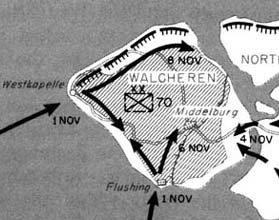

On November 1, 1944, Allied soldiers landed by sea near Vlissingen. At first, there was no resistance, but then the fighting became tough. It took until November 3 to clear the last German soldiers from the Vlissingen area.

On the same day, another landing happened at Westkapelle. This was a very dangerous landing, and the Allied forces lost many soldiers. German coastal guns were very effective, sinking nine Allied ships and damaging ten others. A large battleship, HMS Warspite, helped by firing at the German positions, but some of its shells accidentally hit the town of Domburg, killing 50 civilians. The soldiers fought hard to clear the sand dune areas. By November 3, the landing forces from Westkapelle and Vlissingen met up.

The third part of the attack was a direct assault on German positions behind the Sloe dam, which connected Walcheren to the mainland. Canadian soldiers attacked on October 31, but they faced strong resistance. After two more nights of fighting, they finally managed to get a foothold on November 2. This battle was very costly for both Canadian and British forces. Artillery from across the Scheldt accidentally fired on the village of Arnemuiden, which was a protected place, causing 46 civilian deaths.

On November 5, 1944, the German commander surrendered the city of Middelburg. The last German resistance on Walcheren was cleared by November 8.

The Flooding and Its Effects

Walcheren is shaped a bit like an atoll, with high sand dunes around the edges. The middle part, which is usually dry land, became a shallow "lagoon" after the flooding. Some areas stayed dry (like towns), some were always underwater, and others flooded at high tide and dried out at low tide. The water moved with incredible force through the broken dikes, making the holes wider and deeper.

Most people managed to escape drowning because the water rose slowly. But many animals were not so lucky. When Walcheren was freed, only 600 out of 9,800 cows survived, and 500 out of 2,500 horses.

The long-term effect on the land was also severe. The salty seawater made the very fertile clay soil completely useless for farming for many years. The strong water currents also moved the soil around, washing away the top layer in some places and destroying drainage ditches, roads, and bridges. Buildings were damaged by the waves and by salt soaking into the bricks, which also caused mold. Out of 19,000 homes, about 3,700 were completely destroyed, and many more were severely damaged.

Walcheren was not the only place flooded during World War II. Other parts of the Netherlands were also flooded, mostly by the German army. In the spring of 1945, a huge amount of Dutch farmland was underwater due to seawater, with Walcheren accounting for a significant portion of this.

Life During the "Water Time" in Koudekerke

Life for the people of Walcheren after the fighting stopped was very challenging. Let's look at the village of Koudekerke, located on the southern coast. The locals called the period after the flooding the watertijd ("Water Time").

Because the water rose slowly, people had time to save their recently harvested crops. They moved farm products to the church, which was on higher ground. Many cows were saved by building raised platforms in their stables. Hay was stored in attics. However, many animals had to be killed because there was no way to save them.

People moved their furniture and themselves to the attics of their homes as the ground floors became flooded. They built makeshift walkways to get from house to house in the village. For longer trips, a "ferry service" using lifeboats took people to Vlissingen.

Local delivery services, usually competitors, worked together to transport goods to and from Middelburg. Drinking water was brought daily by horse cart from a German bunker that had a large water tank. People would get their daily water allowance there.

Abandoned German bunkers, which were full of supplies, became a source of food. The local government organized this, allowing people to use their ration books. In fact, the food situation actually improved a bit compared to before the flooding. Walcheren avoided the terrible Dutch famine of 1944–45 that affected other parts of the Netherlands. Sometimes, cargo washed ashore from ships that hit stray mines, adding to their supplies.

Despite these clever solutions, life was very hard, especially in the winter without electricity or normal heating. Many people had to be moved to other safer areas. Even after the island was drained, it took a long time, sometimes until 1946, for homes to get electricity again.

Fixing the Dikes and Drying the Island

Right after Germany surrendered, efforts began to fix the broken dikes. A special organization was set up for this. However, it was very difficult because there weren't enough materials, heavy machines, or skilled workers. Roads and bridges were also damaged, and many areas had dangerous land mines.

It wasn't until the summer of 1945, after the war in Europe ended, that serious repair work could begin. Many dredgers (machines that dig up mud from underwater) were still in German-occupied areas or had been taken to Germany.

By October 1945, a large fleet of dredgers, barges, tugboats, cranes, and bulldozers had been gathered. A big problem was that the breaches in the dikes had become so wide and deep that normal methods couldn't stop the strong tidal flows. The total width of the breaks was three kilometers (almost 2 miles), and some parts were tens of meters deep.

Because of this, new engineering methods were needed. Large concrete boxes called caissons, which were originally built for temporary harbors during the D-Day landings, were used to block the deepest parts of the breaches. Once these caissons broke the force of the tides, more traditional methods could be used to finish the job.

The breach near Vlissingen was first filled on September 3, 1945, but it broke again. It was finally closed on October 2, 1945, almost exactly a year after it was first broken. The Westkapelle breach was closed on October 12, and the Veere breach on October 23. The breach near Ritthem was the last to be closed, on February 5, 1946. Millions of cubic meters of sand, rocks, and bundles of wicker were used, along with many machines and workers.

Closing the dikes stopped the tides, but a huge amount of water was still on the island. Instead of just using pumps, a clever natural method was used. A hole was made in the western bank of the canal through Walcheren. By opening the locks at both ends of the canal during low tide, most of the water drained out by mid-December 1945. After that, the existing pumping stations could drain the rest of the water, and old drainage ditches had to be cleared. The island was finally "dry" again in early 1946.

What Happened Next

After the island was dry, the "Wederopbouw" (the post-war reconstruction) began for Walcheren. One unexpected benefit of the flooding was that it was easier to rearrange agricultural land. Farmers usually resisted this, but since the landscape was "erased" by the flood, a new plan was put in place. This led to farms having much larger fields. Over time, the salt was washed out of the soil, and Walcheren became one of the most productive farming areas in the Netherlands by the 1950s.

It's ironic that when the terrible North Sea Flood of 1953 hit other parts of Zeeland, Walcheren was mostly spared because its dikes had been so recently and strongly rebuilt.

Later, in 1977, an international agreement called Protocol I was made. It added rules to the Geneva Conventions about protecting people during armed conflicts. Articles 53 and 56 of this protocol specifically say that it's against the rules to intentionally destroy dams and dikes. Many countries, including Canada, the Netherlands, and the UK, have agreed to follow this protocol.

The story of how the dikes were repaired and the island was reclaimed from the sea is told in the historical novel Het verjaagde water by A. den Doolaard.

Images for kids

-

Minister Clement Attlee visiting inundated Walcheren in March 1945

-

Laborers preparing a brushwood fascine; in the background obstacles for landingcraft as part of the Atlantic Wall.

See also

- Inundation of the Wieringermeer

Sources

- Bollen, H. and J. Kuiper-Abee (1985) (in nl). Worsteling om Walcheren. Uitgeverij Terra-Zutphen. ISBN 90-6255-228-5.

- Copp, T. (2007). Cinderella Army: The Canadians In Northwest Europe, 1944-1945.

- Gent, T. van (2005). The Allied Assault on Walcheren, 1944 in: C. Steenman-Markusse, and A. van Herk (eds.), Building Liberty: Canada and World Peace, 1945-2005. pp. 11–30. ISBN 9789077922057. https://books.google.com/books?id=JLiSmsWQWuMC&q=Gent%2C+T.+van+%282005%29.+The+Allied+Assault+on+Walcheren%2C+1944&pg=PA10.

- Klep, C. and B. Schoenmaker (1995) (in nl). De bevrijding van Nederland. Oorlog op de flank 1944-1945. Den Haag: Sdu. ISBN 90-12-08191-2.

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |