Operation Infatuate facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Operation Infatuate |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Battle of the Scheldt | |||||||

British assault troops on Walcheren advancing along the waterfront near Flushing with shells bursting ahead - 1 November 1944. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 3,082 Canadians, French (commando KIEFFER) and Royal Marines | 5,000 troops | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1473 casualties including 489 killed, 925 wounded, 59 missing |

1,200 killed and wounded 2,900 captured |

||||||

Operation Infatuate was a special military plan during World War II in November 1944. Its main goal was to open the important port of Antwerp in Belgium. This port was needed to bring in supplies for the Allied forces.

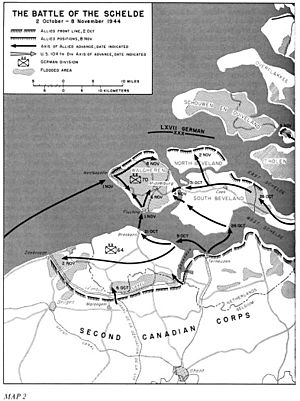

The operation was part of a bigger fight called the Battle of the Scheldt. It involved two sea landings by special British troops and a division of soldiers. At the same time, Canadian soldiers tried to cross a narrow path called the Walcheren Causeway.

Contents

Why the Operation Was Needed

The city of Antwerp and its port were captured by British forces in September 1944. However, the sea route to the port was still blocked. Walcheren Island, located at the mouth of the Scheldt River, was heavily defended by German soldiers. They had strong concrete forts and large guns. These defenses made it impossible for ships to reach Antwerp.

Because of this delay, many German soldiers were able to escape and strengthen their defenses on Walcheren Island. The First Canadian Army was given the job of clearing the Scheldt area. This was very important for getting supplies to the front lines.

On October 9, 1944, Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery ordered the Canadian Army to focus only on clearing the Scheldt. Ten days later, the Canadians began to approach Walcheren Island. The areas south and north of Walcheren had been mostly cleared. Now, it was time to attack Walcheren itself.

Getting Ready for the Attack

The plan involved a three-part attack. British Commandos and part of the 52nd (Lowland) Division would land at Westkapelle on the west side of the island. Other troops would land at Flushing in the south. The 2nd Canadian Infantry Division would try to cross a water channel near the causeway in the east.

However, the water channel near the causeway was too difficult to cross. This left the Canadians with a dangerous direct attack along the causeway. It was a very exposed path, about 40 yards wide and 1,500 yards long.

Lieutenant General Guy Simonds, the acting commander of the First Canadian Army, had a bold idea. He suggested bombing the island's sea walls, called dykes, to flood the inside of the island. This plan was very controversial. Simonds believed it would allow attackers to approach German positions from both the sea and the flooded land.

The plan to flood the island by bombing dykes at Westkapelle, Flushing, and Veere was approved. However, it was not discussed with the Dutch government. When the Dutch Prime Minister found out, he was very upset. The military benefits of flooding were also questioned. It made things harder for both attackers and defenders. German defenses were mostly on the higher parts of the island. Civilians on the island were warned by leaflets to leave, but they had nowhere to go.

In October, RAF Bomber Command bombed the dykes, turning the island into a huge lagoon. The Germans had placed many guns on the dykes, making them a continuous line of defense. British Marines relied on special amphibious vehicles like the Weasel and Buffalo. The Royal Marine Commandos would capture the broken parts of the dykes and then spread out to clear the remaining German defenses. The RAF provided air support, and special armored vehicles helped the ground attack. Warships and landing craft also provided heavy gunfire support.

Special Commando Teams

Special commando units, including No. 2 Dutch Troop and No. 10 (Inter-Allied) Commando, were part of the attack. Some of their members spoke Dutch, which helped them talk with the local people.

Three Royal Marine Commando units, along with Belgian and Norwegian troops, landed at Westkapelle. Another Commando unit, with French troops, crossed from Breskens and attacked Flushing. These units had trained for this difficult assault.

The Landings Begin

After some discussion about the sea conditions, the operation was set for November 1. On the day of the attack, a thick mist covered Dutch and Belgian airfields. This limited air support from the RAF, even though the skies over Walcheren were clear.

Landing at Flushing (Operation Infatuate I)

No. 4 Commando landed at 5:45 AM, just east of a windmill called the Oranjemolen in Flushing. The main group of troops arrived at 6:30 AM.

The commandos had trouble finding a good place to land. A small team went ashore first and secured the beach with few losses. They even took some prisoners. When the main group landed, the Germans were ready. They fired heavily with machine guns and anti-aircraft cannons. Still, the commandos got ashore with only a few injuries. However, landing craft carrying heavy equipment sank close to shore. The equipment was later saved.

The commandos then fought their way through German strongpoints. They had to leave some soldiers behind to prevent Germans from sneaking in. They were helped when the first battalion of the 155th Infantry Brigade began to land. German prisoners were made to help unload supplies. Many of the German defenders were not top-quality troops. By 4:00 PM, the commandos had reached most of their targets and decided to hold their positions as the day ended.

Landing at Westkapelle (Operation Infatuate II)

The plan for Westkapelle involved three groups of No. 41 (Royal Marine) Commando landing on the north side of the dyke gap. Their goal was to clear the area near Westkapelle village. The rest of the commando unit, along with other troops, would land in amphibious vehicles. Their mission was to clear Westkapelle and then move north.

No. 48 (Royal Marine) Commando would land south of the gap and advance towards Zoutelande. Finally, No. 47 (Royal Marine) Commando would land behind them and move to meet up with No. 4 Commando near Flushing.

The landing force left Ostend at 3:15 AM and arrived off Walcheren by 9:30 AM. The ships bombarded the German defenses with all their weapons, including large guns from battleships. German fire began at 8:09 AM and focused on the support landing craft. Several landing craft were hit. The RAF sent fighter-bombers to help just as the landing craft were about to land.

A group of 27 small naval support craft bravely attacked the German shore batteries. They faced heavy fire and suffered many losses. By 12:30 PM, nine of these support craft had been sunk, and eleven were out of action. Many of their crews were killed or wounded. Despite the heavy losses, their goal was achieved: they drew the German fire away from the main landing craft.

General Robert Laycock, a high-ranking officer, praised the bravery of the naval support craft. He said their sacrifice helped the landings succeed and kept casualties low for the special service brigade. Many awards for bravery were given, including the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal to Leading Seaman Owen Joseph McGrath. He rescued over twenty survivors while under heavy enemy fire.

Back on Walcheren Island, 41 Commando quickly took over a German bunker and moved into Westkapelle. They faced a battery of four 94mm guns. These were destroyed with the help of tanks, and the commando then moved north along the dyke.

48 Commando faced a battery of 150mm guns. The lead commander was killed, and several men were wounded. Another attack was met with intense mortar fire. Air support and artillery were called in. After this, another group attacked under smoke cover and put the battery out of action.

The next day, 4 Commando and the 5th Battalion of the King's Own Scottish Borderers continued fighting for Flushing. Norwegian troops from 10 Commando fought bravely against a strong German position called 'Dover'. They used special weapons to attack the strongpoint. After air attacks, the troops advanced and forced the German defenders to surrender.

48 (RM) Commando pushed on and took Zoutelande with little resistance. 47 Commando took over the advance but soon met a strong fortified position with an anti-tank ditch. Bad weather prevented air support, so they attacked with only artillery. They suffered many casualties from mortar fire. Another part of the commando faced another 150mm battery at Dishoek. They cleared resistance until nightfall and then stopped in front of the battery. They fought off a German counterattack after getting much-needed food and ammunition.

Supplying the troops was difficult because of mines and stakes on the beaches. By the third and fourth days, the commandos had to use captured German food. Thankfully, supplies were parachuted in on November 5 near Zoutelande.

Nos. 41 and 10 Commando reached Domburg on the morning of November 2. They met strong resistance. That evening, Brigadier Leicester ordered most of 41 Commando to help 47 Commando in the south. The remaining troops from 10 and 41 Commando finished clearing Domburg. No. 4 Commando was relieved and moved to attack two more batteries northwest of Flushing. They had been fighting for 40 hours and needed rest. Later that day, 47 (RM) Commando overcame resistance at Dishoek and linked up with 4 Commando. Meanwhile, 10 Commando cleared Domburg, with the Norwegian troops showing great courage despite suffering losses.

Captain J. Linzel of No. 10 Commando described the operation as having a big impact on him. He remembered his amphibious vehicle being hit by a grenade, causing chaos and fire. He ended up in another vehicle and landed at Westkapelle, where the fighting was intense. He said it took three days to capture the German dyke at Vlissingen, which had about 300 bunkers.

After the Battle

Nos. 4, 47, and 48 Commandos gathered at Zoutelande and rested for two days while they got new supplies. The remaining German resistance was in the area northwest of Domburg. Nos. 4 and 48 Commando moved to help Nos. 10 and 41. While 41 Commando attacked the last remaining battery, 4 Commando cleared the Overduin woods and pushed towards Vrouwenpolder. This final phase began on November 8.

At 8:15 AM, four Germans approached the Allied troops to discuss a surrender. After some talks, 40,000 German soldiers surrendered. No. 4 Special Service Brigade lost 103 killed, 325 wounded, and 68 missing during eight days of fighting. By the end of November, after a huge effort to clear mines from the Scheldt River, the first cargo ships were able to unload at Antwerp.

Long-Term Effects for Civilians

The flooding of Walcheren, which started Operation Infatuate, had lasting effects on the people living there. Twice a day, at high and low tide, seawater rushed through the broken dykes. This made the breaches wider and deeper. Areas that were normally dry at low tide were flooded again at high tide. Only higher areas, like town centers, stayed dry. Other low-lying areas remained flooded all the time.

This flooding severely damaged farming on Walcheren. Valuable land was ruined by saltwater. Because the flooding happened slowly, not many people drowned. However, most of the farm animals drowned. Of 19,000 homes, 3,700 were destroyed. Another 7,700 had severe damage, and 3,600 had minor damage.

Attempts to close the dyke breaches began in November 1944. But there was a lack of building materials and heavy equipment. The destroyed roads and many minefields also made it hard. By July 1945, when serious work began, the total width of the breaches had grown to three kilometers. The breaches were very deep, so simply moving earth into them wouldn't work.

Instead, large concrete boxes called caissons, which were left over from building artificial harbors, were used to block the deepest parts of the breaches. After that, normal dyke-building could continue. The breach at Flushing was closed on October 2, 1945. The breach at Westkapelle was closed on October 12, and the third breach at Veere was closed on October 23.

Then, the work of draining the flooded areas began. A break was made in the western wall of the Canal through Walcheren. This allowed the main body of water to slowly drain out through the locks at Veere and Flushing during low tide. But to completely drain the area, extra pumping was needed. This also required clearing drainage ditches that had filled with mud. The draining operation was finished in early 1946.

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |