Irish Famine (1740–1741) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Irish Famine (1740–1741)Bliain an Áir |

|

|---|---|

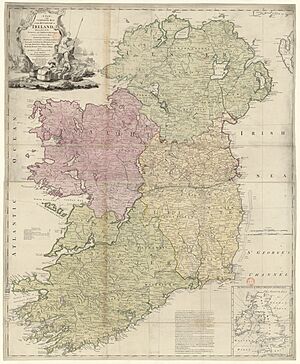

Ireland in the 1730s

|

|

| Country | Kingdom of Ireland |

| Location | Ireland |

| Period | 1740–1741 |

| Total deaths | 300,000–480,000 |

| Relief | See below |

| Impact on demographics | Population fell by 13–20% |

| Consequences | Permanent change in the country's demographic and economic landscape |

| Succeeded by | The Great Famine (An Gorta Mór) |

The Irish Famine of 1740–1741 was a terrible time in Ireland. It is also known as Irish: Bliain an Áir, which means the Year of Slaughter in Irish. During this famine, between 13% and 20% of Ireland's 2.4 million people died. This was a huge loss, even bigger in proportion than the famous Great Famine of 1845–1852.

This famine happened because of very cold and then very dry weather. This extreme weather ruined food supplies in three ways: grain harvests were poor, there wasn't enough milk, and potatoes were damaged by frost. At that time, grains like oats were more important than potatoes for most people's meals.

Many people died from hunger, but also from serious diseases that spread easily during the famine. The cold weather affected all of Europe, but Ireland suffered more because both grain and potato crops failed. Experts now believe this was the last very cold period of the Little Ice Age, which lasted from about 1400 to 1800.

This famine was different from the Great Famine of the 1800s. By the mid-19th century, potatoes were a much bigger part of the Irish diet. So, when a potato disease hit in 1845, it caused a different kind of disaster. The Great Famine was caused by a fungus that destroyed potatoes for several years. It was also made worse by the British government's policies, which allowed food to be sent out of Ireland even as people starved.

Contents

Life in Ireland before the famine

In 1740, about 2.4 million people lived in Ireland. Most people relied on grains like oats, wheat, barley, and rye, along with potatoes, as their main foods. About half of their food money went to grains, 35% to animal products, and the rest to potatoes. Some people lived mostly on oatmeal, buttermilk, and potatoes. It was thought that a person ate about 2.7 to 3.2 kilograms (6 to 7 pounds) of potatoes every day.

What people ate also depended on where they lived and how much money they had. Many added fish from rivers, lakes, or the sea, especially herring, and small wild animals like ducks to their diet. At this time, there was no government help for people in need. Local villages or churches were the only ones who tried to help.

What caused the famine?

A sudden and extreme change in weather hit Ireland and the rest of Europe. This happened between December 1739 and September 1741. No one knows exactly why it happened. But it shows how much climate can affect food, health, money, and even politics.

The Great Frost

In the winter of 1739–1740, Ireland experienced seven weeks of extremely cold weather. This period became known as the "Great Frost." It was so cold that it was "quite outside the Irish experience," as one historian noted.

Rivers, lakes, and even waterfalls froze solid. Many fish died in the frozen waters. People tried to stay warm without using up all their winter fuel too quickly. Those living in the countryside might have been a bit better off. Their cabins were often protected by stacks of turf (dried peat). City dwellers, especially the poor, lived in freezing basements and attics.

The extreme cold also stopped trade. Coal usually came from England and Wales to Irish ports. But the frozen docks and coal yards made this impossible. When ships could finally sail again, the price of coal went way up. Desperate people in Dublin even cut down hedges and trees for fuel. The Frost also froze the water wheels that powered mills. This stopped the grinding of wheat for bakers and other important work.

Potatoes ruined by frost

The Great Frost badly damaged potatoes, which were a main food source for many rural Irish people. Potatoes were usually stored in the ground in special piles called potato clamps. These clamps were made with layers of soil and straw to protect the potatoes from frost. But the Frost was so severe that it froze and destroyed the potatoes. This meant people had no food and no seeds for the next planting season.

Spring drought in 1740

After the Frost, the expected spring rains did not come. The weather stayed cold, and strong winds blew. This long dry spell killed many farm animals, especially sheep and cattle.

By late April, the drought had ruined much of the grain crops planted the previous autumn. Grains were even more important than potatoes in people's diets. The lack of corn crops caused more deaths in Ireland than in Britain or other parts of Europe.

Food became so scarce that the Catholic Church allowed people to eat meat during Lent. But many people were too poor to buy meat. The potato crisis also made grain prices soar. This meant bread loaves became smaller and smaller for the same price. By summer 1740, the Frost had destroyed potatoes, and the drought had ruined grain harvests and animal herds. Starving people began to move towards towns like Cork, hoping to find food. By mid-June, beggars filled the streets.

Food riots and protests

As food prices rose, hungry townspeople became angry. They often protested at markets or warehouses where food was stored. The first protest happened in Drogheda in mid-April. A group of citizens stopped a ship full of oatmeal that was about to leave for Scotland. They removed parts of the ship to prevent it from sailing. Officials then made sure no more food left their port.

In Dublin, a riot broke out in late May 1740. People believed bakers were hiding bread. They broke into bakeries and sold some loaves, giving the money to the bakers. Others simply took the bread. The next day, rioters took meal from mills outside the city and sold it cheaply. Soldiers tried to stop the riots and killed several people. City officials tried to find people hoarding grain, but prices stayed very high all summer.

Similar protests over food happened in other Irish cities. The War of the Austrian Succession also began around this time. Spanish privateers (ships allowed to attack enemy ships) captured vessels heading for Ireland, including those carrying grain. This war also put Ireland's main exports, like linen and salted meat, at risk.

The cold returns

In autumn 1740, a small harvest began, and food prices in towns started to drop. Cattle began to recover. But in areas where dairy farming was common, many cows were too weak after the Frost to have calves. This led to a shortage of milk, which was a common drink, and less butter.

To make things worse, snowstorms hit the east coast in late October 1740 and again in November. A huge rainstorm on December 9, 1740, caused widespread flooding. The day after the floods, temperatures dropped sharply, snow fell, and rivers froze again. After about ten days, warmer weather returned. Large chunks of ice floated down the Liffey River through Dublin, damaging boats.

The strange autumn of 1740 pushed food prices up again. Wheat prices in Dublin reached a record high by December 20. The ongoing wars also encouraged people with stored food to keep it for themselves. People desperately needed food, and riots broke out again across the country. By December 1740, it was clear that a full-blown famine and disease outbreak were happening in Ireland.

Helping people during the famine

The Lord Mayor of Dublin, Samuel Cooke, met with important leaders on December 15, 1740. They wanted to find a way to lower the price of corn. One leader, Archbishop Boulter, started an emergency food program for the poor in Dublin using his own money. The government also ordered officials in each county to count all the grain held by farmers and merchants.

These reports showed that a lot of grain was held privately. For example, County Louth had over 85,000 barrels of grain. Some wealthy landowners, like the widow of William Conolly, helped people on their own. She and others gave out food and money during the "black spring" of 1741. They also hired workers for local projects like building an obelisk, paving roads, and cleaning harbors. In Drogheda, a judge named Henry Singleton used much of his own money to help with famine relief.

Weather returns to normal

In June 1741, five ships carrying grain, likely from America, arrived in Galway on the west coast. In the first week of July 1741, grain prices finally dropped. Old, hidden wheat suddenly appeared on the market. The autumn harvest of 1741 was okay, and the food crisis was over. The next two years even had plenty of food.

How many people died?

It's hard to know exactly how many people died during the Great Frost because records were not kept well. For example, in one church parish, 47 children were buried in just two months. The normal death rate tripled in January and February 1740. Overall, burials were about 50% higher during the 21-month crisis than in the years before.

Historians believe that between 13% and 20% of the population died. This means that between 300,000 and 480,000 people may have died in Ireland. The highest death rates were in the south and east of the country. This was a greater loss of life, in proportion to the population, than during the Great Famine of 1845–1849. However, the Great Famine lasted longer and had different causes.

What we learned

The Irish Great Frost of 1740–1741 showed how people behave during a crisis. It also showed the huge impact a major climate event can have on society, money, and health. After the crisis eased, the population began to grow quickly. Even though other famines happened later in the 1700s, this one was especially severe. People did not leave Ireland in large numbers right after this famine. This was probably because conditions improved fairly quickly, and traveling across the ocean was too expensive for most people.

The year 1741, when the famine was at its worst, is still remembered in Irish folk stories as the "year of the slaughter" or bliain an áir.

|

See also

- Irish Famine (1879)

- List of famines

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |