Isabella Furnace facts for kids

Quick facts for kids |

|

|

Isabella Furnace

|

|

The furnace in ruins in 1959.

|

|

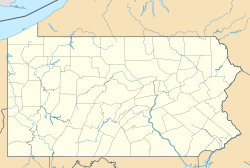

| Nearest city | Brandywine Manor, Pennsylvania |

|---|---|

| Area | 4 acres (1.6 ha) |

| Built | 1835 |

| Architectural style | Iron furnace |

| MPS | Iron and Steel Resources of Pennsylvania MPS |

| NRHP reference No. | 91001135 |

| Added to NRHP | September 06, 1991 |

Isabella Furnace was an old-fashioned iron-making factory located in West Nantmeal Township, Chester County, Pennsylvania. It was called Isabella Furnace after Isabella Potts, whose husband was one of the owners. Her family, the Potts, were famous for making iron.

Isabella Furnace was the very last iron furnace built in Chester County, in 1835. The Potts family and their partners ran it until 1855. They lost control of it for a while due to money problems. But in 1881, Col. Joseph Potts, Isabella's nephew, bought it back. He made it more modern.

This furnace was the last one to work in Chester County. It stopped making iron in 1894, shortly after Col. Potts passed away. The furnace building stayed mostly whole until 1943. Today, the remains of Isabella Furnace are a protected historic site, listed on the National Register of Historic Places since 1991.

Contents

The Story of Isabella Furnace: Making Iron in the Past

Building the Furnace: A Family Business Begins

The first people to run Isabella Furnace were Henry Potts and his brother-in-law, John Potts Rutter. They bought land for the furnace on April 1, 1835. This land was next to Perkins Run, a small stream that flowed into the East Branch Brandywine Creek. The land already had a mill for cloth and a sawmill. The deal also gave them rights to use the stream's water to power the furnace.

The Potts and Rutter families were already big in the iron business near Philadelphia. Henry's father was a partner in another iron-making place called Glasgow Forge. Henry himself worked at other furnaces, including Warwick Furnace. Isabella Furnace was finished by the end of 1835. It was named after Henry's wife, Isabella. It turned out to be the last large furnace built in northern Chester County.

New Partners and Challenges

In 1836, Henry's brother David joined as a partner and manager. Henry kept half ownership, and David and John each had a quarter. The furnace got its iron ore from nearby mines like Jones and Warwick. Other family members, from the Potts, Rutter, and Brooke families, were also partners in these mines.

Later, in 1839 and 1840, Henry and David's other brothers, Robert Smith Potts and Joseph Potts, also joined the business. Eventually, David bought out most of the family's shares. The furnace did well under David's leadership. In 1850, it made about 1,000 short tons (910 t) of iron each year. In 1853, the furnace was changed into a forge, which is a place where metal is shaped by heating and hammering.

However, the iron market changed in the mid-1850s. This caused big money problems for David. Isabella Furnace was then sold to John Irey and James Butler.

New Owners and the Civil War Era

John Irey was a carpenter who had also worked with iron. Under the new owners, the forge made about 560 short tons (510 t) of iron pieces called "blooms" in 1856. Irey bought out Butler in 1860 and ran the forge by himself.

During the early years of the American Civil War, a railway called the East Brandywine and Waynesburg Railroad was built nearby. It passed about half a mile south of the forge. This new train line made it easier to ship the iron products. The forge was updated in 1864. It was probably at this time that it became a furnace again. But Irey's business during the Civil War was not making money.

Return to the Potts Family and Modernization

In 1865, Irey sold the furnace to the Smith brothers: Bentley H., William D., and Horace V. They were also from a family known for making iron. William D. and Horace V. Smith managed the furnace until 1881. Around 1870, another railway, the Wilmington and Reading Railroad, built a station called "Isabella" about a mile away.

In 1880, Col. Joseph D. Potts, David Potts's son, came back to the area. He had grown up at Isabella Furnace and thought of it as home. Col. Potts had become very rich working in the railroad business. When he retired, he wanted to return to iron-making, just like his family before him. He convinced the Smith brothers to sell, even though they didn't really want to. He bought the property on February 28, 1880.

Col. Potts was ready to spend a lot of money to make the furnace modern. He changed it from using water power to more reliable steam power to create the blast of air needed for the furnace. He also arranged for a special train track to be built to the furnace from the East Brandywine and Waynesburg line. This made it much easier to bring in raw materials and ship out the iron.

By 1884, Isabella Furnace was using local iron ores mixed with ore from Spain. It produced a special type of iron called "car-wheel pig iron" under the "Wyebrooke" brand. This type of iron was good for making train car wheels. Because of the updates, the furnace could now make 3,000 short tons (2,700 t) of iron each year. Col. Potts made his older son, William M. Potts, the manager. His younger son, Francis L. Potts, also worked there for a few years.

The Final Years of Operation

In 1886, Isabella Furnace was rebuilt one last time. By 1892, it was using a mix of local ores, ore from Lancaster County, Elba (an island), and Lake Superior. Its yearly capacity had grown to 6,000 short tons (5,400 t).

In 1891, Col. Potts started building a large, castle-like house nearby called "Langoma." He planned for it to be his home and his son William's. But he died in December 1893 and never saw it finished. William, his wife, and mother moved into "Langoma." However, iron-making at the furnace stopped in April 1894, not long after Col. Potts's death. It was the last iron furnace to operate in Chester County.

The furnace and its train track were left mostly untouched, even though they weren't used. Over time, the furnace slowly fell apart, which created a unique look. One writer in 1935 described it as looking like "a Persian mosque." This slow decay sped up after William M. Potts died in 1943. The railroad tracks were removed, and other metal parts were taken for scrap. Even after this, a photographer in 1959 said the furnace looked "quite striking" in its wild, overgrown setting.

After William Potts died, the ruined furnace was sold to Frank Bloise. In 1945, it was sold again to Langoma Industries, a clothing company. They planned to build a clothing factory and a town for workers on the Potts estate. The company still owned it in 1959. Eventually, the property became a private home.

What Was Inside: Buildings of the Furnace Complex

The Furnace Stack and Its Changes

The main part of the furnace was its "stack," a tall, chimney-like structure. The original stack was 33 feet (10 m) high. The bottom part, called the "bosh," was 6.5-foot (2.0 m) wide.

During later updates in 1864 or 1881, the stack was made taller, reaching 35 feet (11 m), and the bosh became 7.75-foot (2.36 m) wide. The very last update in 1886 made the stack even bigger, reaching 60 feet (18 m) tall.

Other Important Buildings

A map from 1890 shows many buildings arranged on the hillside leading down to Perkins Run.

- Coalhouse, Orehouse, and Screenhouse: These were large warehouses on top of the hill. They were about 100 feet long and 50 feet wide. Train tracks ran into them to deliver and store raw materials like charcoal and iron ore.

- Crusher House and Charging House: Because the warehouses were on a hill, charcoal and ore could be easily moved to these buildings. Here, the ore was crushed.

- Charging Bridge: The mixed charcoal and ore would then go across this bridge into the very top of the furnace stack. The bottom of the stack was at the foot of the hill.

- Wheel House: This building was attached to the base of the furnace. It was used for storing things like casting sand and special "fire bricks" that could handle high heat.

- Casting House: This is where the hot, melted iron flowed out of the furnace into molds to create iron shapes.

- Boiler Shed and Blowing Engine: Nearby, these buildings housed the steam-powered engine that created the strong blast of air (called "tuyeres") needed for the furnace to work.

- There were also other smaller buildings in the flat area around Perkins Run.

Today, some of these buildings, like the coalhouse, casting house, crusher house, and blowing engine house, have new roofs. They seem to be part of a private home. The main furnace stack is mostly gone, and other buildings have disappeared. However, you can still see the foundations and lower walls of the orehouse and screenhouse.