J. D. Salinger facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

J. D. Salinger

|

|

|---|---|

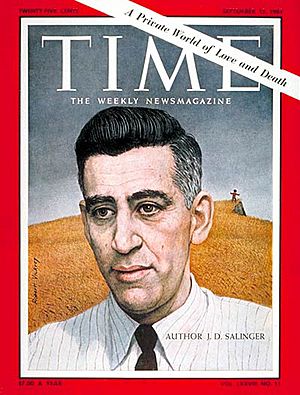

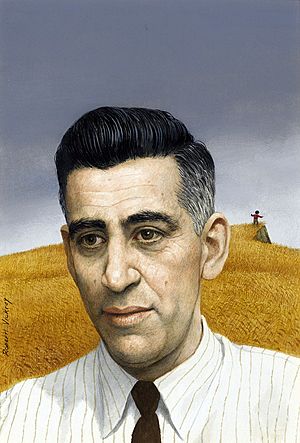

Salinger in 1950

|

|

| Born | Jerome David Salinger January 1, 1919 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | January 27, 2010 (aged 91) Cornish, New Hampshire, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Education |

|

| Notable works |

|

| Spouse |

|

| Children | 2, including Matt |

| Signature | |

Jerome David Salinger (born January 1, 1919 – died January 27, 2010) was an American writer. He is most famous for his 1951 novel The Catcher in the Rye.

Salinger started publishing short stories in Story magazine in 1940. He then served in World War II. In 1948, his well-known story "A Perfect Day for Bananafish" appeared in The New Yorker magazine. This magazine published many of his later works.

The Catcher in the Rye became very popular right away, especially with teenagers. The book was widely read and also caused some debate. Its success brought Salinger a lot of public attention. Because of this, Salinger became very private and published less often. After Catcher, he released a collection of short stories called Nine Stories (1953). He also published Franny and Zooey (1961) and Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour: An Introduction (1963). Salinger's last published work was a story called Hapworth 16, 1924. It appeared in The New Yorker in 1965.

Contents

Early Life and School Days

Jerome David Salinger was born in Manhattan, New York, on January 1, 1919. His father, Sol Salinger, sold Kosher cheese. His mother, Marie, changed her name to Miriam after marrying his father. Salinger had one older sister, Doris.

As a young boy, Salinger went to public schools in Manhattan. In 1932, his family moved to Park Avenue. Salinger then went to McBurney School, a private school nearby. He found it hard to fit in there. He even tried to call himself Jerry to be more like others. His family called him Sonny.

At McBurney, he helped with the fencing team and wrote for the school newspaper. He also acted in plays. His parents then sent him to Valley Forge Military Academy in Wayne, Pennsylvania. Here, Salinger started writing stories secretly at night with a flashlight. He was the literary editor for the school yearbook. He also joined several clubs.

Salinger was an average student at Valley Forge. He graduated in 1936. He started at New York University in 1936 but left the next spring. His father wanted him to learn about the meat business. Salinger went to work in Vienna and Poland. He disliked the slaughterhouses so much that he decided to become a writer instead. He left Austria before it was taken over by Nazi Germany in 1938.

In 1938, Salinger went to Ursinus College for one semester. He wrote a column there about movies. In 1939, he took a writing class at Columbia University. His teacher, Whit Burnett, was an editor for Story magazine. Salinger's first short story, "The Young Folks," was published in Story in 1940. Burnett became Salinger's mentor.

Serving in World War II

In 1942, Salinger dated Oona O'Neill, the daughter of a famous writer. Their relationship ended when Oona started seeing Charlie Chaplin. She later married Chaplin.

Around this time, Salinger started sending stories to The New Yorker. The magazine turned down many of his stories. But in December 1941, they accepted "Slight Rebellion off Madison." This story was about a troubled teenager named Holden Caulfield. However, the story was not published then because of the attack on Pearl Harbor. It finally appeared in The New Yorker in 1946.

In the spring of 1942, Salinger was drafted into the army. He fought in World War II with the 12th Infantry Regiment. He was at Utah Beach on D-Day. He also fought in the Battle of the Bulge and the Battle of Hürtgen Forest.

During the war, Salinger met Ernest Hemingway, a writer he admired. Hemingway was a war reporter in Paris. Salinger was impressed by Hemingway's kindness. Hemingway was also impressed by Salinger's writing. They started writing letters to each other. Salinger later said their talks were some of his few good memories from the war.

Salinger worked in a counter-intelligence unit. He used his French and German skills to question prisoners of war. In April 1945, he entered Kaufering IV, a subcamp of Dachau. Salinger became a Staff Sergeant. His war experiences deeply affected him. He was hospitalized for a few weeks due to combat stress reaction. He later told his daughter that the smell of burning flesh from the camps never truly leaves you. Biographers believe his war experiences influenced stories like "For Esmé—with Love and Squalor." Salinger kept writing during the war. He published stories in magazines like Collier's and The Saturday Evening Post.

After the War and Famous Books

After Germany was defeated, Salinger stayed in Germany for six months. He helped with "Denazification" duties. He married Sylvia Welter there. They came to the United States in 1946, but their marriage ended after eight months. Sylvia returned to Germany.

In 1948, his popular story "A Perfect Day for Bananafish" was published in The New Yorker. This story was the first to feature the Glass family. This fictional family included two retired performers and their seven children. Salinger wrote seven stories about the Glasses. He focused a lot on Seymour, the oldest child.

In 1951, Salinger's first novel, The Catcher in the Rye, was published. It quickly became a huge success.

Life in the 1950s and Moving Away

As The Catcher in the Rye became more famous, Salinger started to avoid public attention. In 1953, he moved from New York City to Cornish, New Hampshire. At first, he was quite friendly there. He often invited students from Windsor High School to his home. They would listen to music and talk about school problems. One student convinced Salinger to do an interview for the local newspaper. After the interview was published, Salinger stopped talking to the students. He also became less visible around town. He only regularly met one close friend, a judge named Learned Hand.

Salinger also started to publish less often. After Nine Stories, he only published four more stories in the 1950s.

In February 1955, Salinger, at age 36, married Claire Douglas. She was a student at Radcliffe College. They had two children, Margaret (born 1955) and Matthew (born 1960). Salinger asked Claire to leave college just before she graduated, and she did.

The Salingers divorced in 1967. Claire got custody of the children. Salinger built a new house across the road from their old home. He stayed close to his family and visited often. He lived in Cornish until he died.

Last Published Works

Salinger published Franny and Zooey in 1961. He then published Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour: An Introduction in 1963. Each book contained two stories that had appeared in The New Yorker. These were the only stories Salinger had published since Nine Stories.

In September 1961, Time magazine featured Salinger on its cover. The article talked about his private life. It said that his Glass family stories were not finished. It also mentioned that Salinger planned to write a Glass family trilogy. However, Salinger only published one more work after that. It was "Hapworth 16, 1924," a long story in the form of a letter. It was written by seven-year-old Seymour Glass from summer camp. This story was his first new work in six years. It filled most of The New Yorker's June 19, 1965, issue. Critics did not like it.

Salinger continued to write every morning. In a 1974 interview, he said, "There is a marvelous peace in not publishing... I like to write. I love to write. But I write just for myself and my own pleasure." His daughter, Margaret Salinger, said her father had a detailed system for his unpublished writings. He used different colored marks to show if a work should be published "as is" or edited first after his death. A neighbor said Salinger told him he had written 15 unpublished novels.

Salinger was involved with actress Elaine Joyce in the 1980s. He later met Colleen O'Neill, a nurse, and married her around 1988.

Death and Later Publications

J. D. Salinger died at his home in New Hampshire on January 27, 2010. He was 91 years old.

Salinger wrote throughout his life. After he passed away, his wife and son started getting his unpublished works ready. In 2019, they announced that "all of what he wrote will at some point be shared." However, they said it was a big job and not ready yet.

Writing Style and Themes

In 1946, Salinger wrote that he "almost always write[s] about very young people." Teenagers or young people appear in all of his stories. This includes his first story, "The Young Folks" (1940), and his famous novel The Catcher in the Rye.

One critic, Alfred Kazin, said in 1961 that Salinger's focus on teenagers made him popular with young readers. He also said that Salinger seemed to speak directly to them. He used language that felt honest and real to them. Salinger's writing style, especially his lively and realistic conversations, was new and exciting when his first stories came out. Many critics thought it was the most special thing about his work.

Salinger felt a strong connection to his characters. He used methods like inner thoughts, letters, and long phone calls to show his talent for dialogue.

Some common themes in Salinger's stories are:

- The idea of innocence and being young.

- How the adult world can seem "fake" or corrupting to teenagers.

- The smart and wise way children often see the world.

List of Works

Books

- The Catcher in the Rye (1951)

- Nine Stories (1953)

- "A Perfect Day for Bananafish" (1948)

- "Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut" (1948)

- "Just Before the War with the Eskimos" (1948)

- "The Laughing Man" (1949)

- "Down at the Dinghy" (1949)

- "For Esmé—with Love and Squalor" (1950)

- "Pretty Mouth and Green My Eyes" (1951)

- "De Daumier-Smith's Blue Period" (1952)

- "Teddy" (1953)

- Franny and Zooey (1961)

- "Franny" (1955)

- "Zooey" (1957)

- Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour: An Introduction (1963)

- "Raise High the Roof-Beam, Carpenters" (1955)

- "Seymour: An Introduction" (1959)

Collected Short Stories

- Three Early Stories (2014)

- "The Young Folks" (1940)

- "Go See Eddie" (1940)

- "Once a Week Won't Kill You" (1944)

Published Stories (Not in Collections)

- "The Hang of It" (1941)

- "The Heart of a Broken Story" (1941)

- "Personal Notes of an Infantryman" (1942)

- "The Long Debut of Lois Taggett" (1942)

- "The Varioni Brothers" (1943)

- "Both Parties Concerned" (1944)

- "Soft-Boiled Sergeant" (1944)

- "Last Day of the Last Furlough" (1944)

- "Elaine" (1945)

- "The Stranger" (1945)

- "I'm Crazy" (1945)

- "A Boy in France" (1945)

- "This Sandwich Has No Mayonnaise" (1945)

- "Slight Rebellion off Madison" (1946)

- "A Young Girl in 1941 with No Waist at All" (1947)

- "The Inverted Forest" (1947)

- "Blue Melody" (1948)

- "A Girl I Knew" (1948)

- "Hapworth 16, 1924" (1965)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: J. D. Salinger para niños

In Spanish: J. D. Salinger para niños