Jacobo Timerman facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jacobo Timerman

|

|

|---|---|

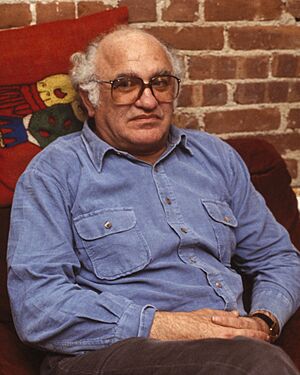

Timerman c. 1980

|

|

| Born | 6 January 1923 Bar, Ukrainian SSR, Soviet Union |

| Died | 11 November 1999 (aged 76) Buenos Aires, Argentina |

| Occupation | journalist, editor, author |

| Language | Spanish |

| Nationality | Argentine |

| Citizenship | Argentine, Israeli |

| Subject | human rights |

| Notable works | Preso sin nombre, celda sin número, 1980 (Prisoner Without a Name, Cell Without a Number, 1981), Israel: la guerra más larga. La invasión de Israel al Líbano,1982 (The Longest War: Israel in Lebanon, 1982) Chile, el galope muerto (1987), Cuba: un viaje a la isla (1990) |

| Notable awards | ADL's Hubert H. Humphrey First Amendment Freedom Prize, Golden Pen of Freedom, Conscience-in-Media Award, Letelier-Moffitt Human Rights Award, Order of the Liberator General San Martín, World Press Freedom Hero |

| Spouse | Risha Mindlin |

| Children | Héctor Timerman, Javier Timerman, Daniel Timerman |

Jacobo Timerman (born January 6, 1923 – died November 11, 1999) was a brave journalist, editor, and author from Argentina. He was born in the Soviet Union. Timerman became famous for speaking out against the terrible things that happened during Argentina's "Dirty War" in the late 1970s. This was a time when the military government arrested and made many people disappear.

Because he reported on these events, Timerman was arrested and put in prison by the Argentine military. In 1979, he and his wife were forced to leave Argentina and move to Israel. He was highly respected around the world for his important work.

While in Israel, Timerman wrote his most famous book, Prisoner Without a Name, Cell Without a Number (1981). This book shared his difficult experiences in prison and made his international reputation even stronger. He was also a strong supporter of Israel for a long time. However, he later wrote another book, The Longest War, which was very critical of Israel's actions in the 1982 Lebanon War.

Timerman returned to Argentina in 1984. He gave important information to a special group investigating the disappeared people. He kept writing, publishing books about Chile under Augusto Pinochet in 1987 and about Cuba under Fidel Castro in 1990.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Jacobo Timerman was born in Bar, Ukraine. His parents, Eve Berman and Nathan Timerman, were Jewish. To escape difficult times for Jewish people in Ukraine, his family moved to Argentina in 1928 when he was five years old. They lived in a Jewish area of Buenos Aires and were very poor, living in just one room. Timerman started working at age 12 after his father passed away. When he was young, he lost one eye due to an infection.

As a young man, Timerman became a Zionist, meaning he supported the idea of a Jewish homeland in Israel. He met his future wife, Risha Mindlin, at a Zionist meeting in Mendoza. They got married on May 20, 1950.

Career as a Journalist

Starting in Journalism

Timerman began his career as a journalist and quickly became successful. He wrote for many different newspapers and magazines, including Agence France-Presse. He learned to speak English very well, in addition to Spanish. He gained a lot of experience reporting on politics in Argentina and other South American countries.

In 1962, Timerman started his own news magazine called Primera Plana in Argentina. People often compared it to Time magazine in the United States. In 1964, Timerman left Primera Plana because there were rumors that the government was threatening publications that disagreed with them.

In 1965, he started another news magazine called Confirmado.

Founding La Opinión

In 1971, Timerman founded La Opinión, which many people thought was the best work of his career. With this newspaper, Timerman started to cover topics in more detail. Journalists also began to sign their articles, so readers knew who wrote them. He was inspired by the French newspaper, Le Monde.

La Opinión reported on the news and criticized the human rights problems of the Argentine government, especially during the early years of the "Dirty War". Timerman believed his newspaper was the only one brave enough to report the truth without hiding what was happening. He received many threats because of his outspoken reporting.

Timerman also strongly supported Israel. In 1975, he wrote an article called "Why I Am A Zionist" after the United Nations passed a resolution that said Zionism was a form of racism.

Military Rule and Arrest

In 1976, the military took control of Argentina. This began a period called "el Proceso" (the Process), which led to widespread persecution known as Argentina's "Dirty War". At first, Timerman, like many others, thought the military takeover might stop the violence in the country.

Timerman continued to publish La Opinión for a year after the military took power. He later thought that some moderate people in the military kept his paper going because it looked good to other countries.

However, anti-Jewish feelings grew stronger in the 1970s. Jewish people were targeted in the media, even on government TV channels. In April 1977, the military started arresting people connected to a businessman named David Graiver, who was suspected of helping a leftist group.

On April 15, 1977, military police arrested Timerman at his home. The Army announced that he and others were being held because of the "Graiver case." The government took control of La Opinión in May 1977, and the newspaper eventually closed down.

Release and Moving to Israel

On September 19, 1979, the highest court in Argentina ordered Timerman's release. After some discussion, the government agreed to let him go. On September 25, he was sent on a flight to Madrid, on his way to Israel. His Argentine citizenship was taken away. He arrived in Israel just in time for a Jewish holiday called Yom Kippur. His wife and three sons also moved to Israel.

In Israel, Timerman was given Israeli citizenship. The military in Argentina had taken all his money and property there. He sold a summer home he owned in Uruguay.

Writing His Famous Books

Prisoner Without a Name

In Tel Aviv, Israel, Timerman wrote and published Prisoner Without a Name, Cell Without a Number in 1981. This book was about his difficult time in prison in Argentina and also discussed the bigger political issues there. The book quickly became popular around the world. Timerman was invited to speak about his experiences in many countries, which helped more people learn about the human rights situation in Argentina.

The book shared new details about the military government in Argentina. For example, it described how police and military officers were taught that they were fighting a "World War III" against leftist groups. The book also showed how the military government had anti-Jewish and anti-intellectual ideas. In 1983, the book was made into a TV movie.

Many people praised Prisoner Without a Name. One journalist compared it to important books by famous authors like Arthur Koestler and Alexander Solzhenitsyn. However, the Argentine government was not happy. They said Timerman was trying to make Argentina look bad around the world.

Speaking Out in the U.S.

In 1981, Timerman spoke out against U.S. President Ronald Reagan's choice for a human rights position. Timerman believed that a country's human rights policy should save lives, and he said that "quiet diplomacy" was like "silent diplomacy," which didn't help people. He argued that the U.S. should continue to speak up for human rights.

His strong words helped stop the person Reagan had chosen from getting the job. Some conservative critics in the U.S. criticized Timerman, but his experiences were used by others to argue for stronger human rights policies.

The Longest War

After finishing his prison memoir, Timerman went to Lebanon to see Israel's 1982 war up close. This experience deeply bothered him, even though he had been a strong supporter of Israel for most of his life. He then wrote a book called The Longest War: Israel's Invasion of Lebanon (1982).

Timerman was also upset by Israel's control of Palestinian land. He wrote that Israelis were "exploiting, oppressing, and victimizing" Palestinians, which made the Jewish people "lose their moral tradition." In the book, he shared that he advised his son Daniel to go to jail rather than serve in the military during the Lebanon war. Daniel followed his advice and was sent to prison.

Some critics called the book "pro-Palestinian" and said it showed Israel as the attacker in the conflict. Timerman even compared Israel's treatment of Palestinians to South Africa's treatment of Black people under Apartheid. He also criticized U.S. policy in the Middle East.

Timerman was one of the first and most outspoken Israeli critics of the war. Because he was a Zionist and a human rights advocate, his opinion was hard to ignore. However, his views were not popular among many Israelis. Some Israeli officials criticized him, saying he was attacking Israel. After this, some Israelis and American Jews avoided him.

Later Journeys and Return to Argentina

After The Longest War was published, Timerman and his wife left Israel. He felt disappointed by the Israeli state. He moved to Madrid and then to New York.

Timerman was very happy when Raúl Alfonsín was elected president of Argentina in 1983, saying it started a "completely new" era of democracy. On January 7, 1984, Jacobo and Risha returned to Buenos Aires. One of their sons stayed in Israel, another settled in New York, and a third returned to Argentina.

Timerman kept his Israeli citizenship. When he returned to Argentina, he shared his prison experiences with the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons. He even visited the prisons where he had been held.

In 1985, many people were put on trial for crimes committed during the Dirty War. However, in 1986, a law was passed that stopped further prosecutions.

Timerman became the director of a newspaper called La Razón and continued to write articles for other papers. He kept criticizing the government of Israel for what he saw as its problems. He noticed that some Americans and Israelis who had given him awards before were now unhappy with his criticism of Israel.

Chile: Death in the South

In 1987, Timerman released Chile: Death in the South. This book looked closely at life under the dictator Augusto Pinochet. The book showed the poverty, hunger, and violence caused by Pinochet's military rule. It also argued that Chilean society had lost its cultural depth because of the political repression.

Cuba: A Journey

Timerman's 1990 book about Cuba criticized both the Communist government and the negative effects of the U.S. blockade on Cuba. He suggested that not much political change could happen in Cuba until Fidel Castro was no longer in charge.

Continued Fight for Freedom

Timerman was one of the first to criticize Carlos Saúl Menem, who later became president of Argentina. In 1988, Timerman criticized Menem's plans for a free port, saying it would encourage illegal money activities. Menem sued Timerman for libel, but Timerman won the case. Timerman continued to oppose Menem during his election campaign.

Menem was elected president in 1989. In 1991, he pardoned important figures who had been found guilty of kidnapping and disappearances during the Dirty War. Timerman strongly condemned Menem for these pardons.

Timerman warned that Argentina was starting to slip back into a totalitarian system. In 1996, he helped start a press freedom organization in Buenos Aires called Periodistas.

Later Life and Passing

After his wife's death in 1992, Timerman became very sad. His health also began to fail in his last years. However, he continued to fight for press freedom. He passed away from a heart attack in Buenos Aires on November 11, 1999.

After His Death

In 2003, the Argentine Congress removed the law that had stopped prosecutions for Dirty War crimes. The government reopened investigations. In 2006, Miguel Etchecolatz, who had overseen Timerman's arrest, was found guilty and sent to prison. In 2007, a Catholic priest, Christian Von Wernich, was also found guilty of being involved in the abduction of Timerman and many other political prisoners. He was sentenced to life in prison.

Legacy and Awards

Jacobo Timerman received many honors for his courage and dedication to human rights and press freedom:

- In 1979, he won the Hubert H. Humphrey First Amendment Freedom Prize.

- In 1980, he received the Golden Pen of Freedom from the World Association of Newspapers.

- His 1981 book, Prisoner Without a Name, earned him several awards, including the Conscience-in-Media Award, the Hillman Prize, and the Letelier-Moffitt Human Rights Award.

- In 1984, Argentine President Raúl Alfonsín gave him The Order of the Liberator General San Martín, which is Argentina's highest honor.

- In 2000, after his death, Timerman was named one of the International Press Institute's 50 World Press Freedom Heroes of the past 50 years.

Family Life

Jacobo and Risha Timerman had three sons. When they moved to Israel, their sons went with them. The Timermans returned to Argentina in 1984.

Daniel Timerman settled in Israel, where he had three children. When he was young, he was sent to prison several times for refusing to serve in the 1982 Lebanon war.

Héctor Timerman also returned to Argentina and became a journalist and author. He later served as Argentina's Foreign Minister. Before that, he was a Consul in New York and Ambassador to the United States.

Javier Timerman settled in New York with his wife and three children.

See also

In Spanish: Jacobo Timerman para niños

In Spanish: Jacobo Timerman para niños

- History of the Jews in Argentina

- Andrew Graham-Yooll

- List of memoirs of political prisoners

- Héctor Germán Oesterheld

- List of war films based on books (post-1945)