Jan Janszoon van Hoorn's expedition of 1633 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Jan Janszoon van Hoorn's expedition of 1633 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Thirty Years' War | |||||||

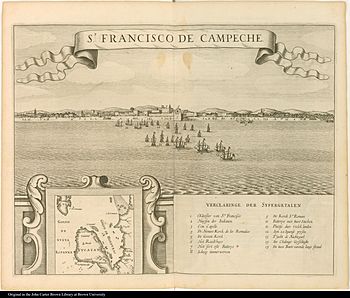

S. Francisco de Campeche, engraving for 1644 Historie by Joannes de Laet |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

|

||||||

The Jan Janszoon van Hoorn's expedition of 1633 was a journey led by a privateer (a private ship allowed to attack enemy ships) for the Dutch West India Company (WIC). This company was a Dutch trading and exploration group. Their mission was to attack Spanish areas in Honduras and Yucatan (part of New Spain). This happened during the Eighty Years' War, a long conflict between the Netherlands and Spain.

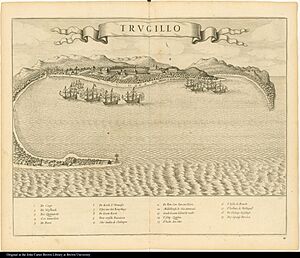

The expedition was a success for the Dutch. They attacked and looted Campeachy and also attacked and burned Trujillo. Because of this attack, Trujillo was left without defenses for many years.

Contents

Planning the Attack

After the Dutch West India Company (WIC) famously captured the Spanish silver fleet in 1628, they became very confident. Admiral Piet Heyn suggested attacking Trujillo, Honduras. In 1630, two men, Jan Booneter and Adriaen Pater, were told to try and surprise the Spanish silver fleet in Trujillo's port if they could. This plan didn't work out.

Later, in 1632, the WIC asked Galeyn von Stapels to map the coastlines and waters of the Bay of Campeachy, the Yucatan Peninsula, and the Bay of Honduras. Then, on November 2, 1632, the WIC gave Jan van Hoorn the order to sail to the Bay of Honduras and attack Trujillo.

The Journey Begins

Setting Sail

Van Hoorn's fleet left Pernambuco (which is now in Dutch Brazil) on April 26, 1633. They arrived at Bridgetown, Barbados, on May 20. The crew spent seven days getting fresh water there before sailing west. On June 18, they saw the eastern tip of Puerto Rico.

On July 5, they dropped anchor near Little Cayman. Two days later, two smaller ships, the Nachtegael and the Gijsselingh, joined them. These ships had been looking for valuable prizes (captured enemy ships or goods) off Cape Cruz, Cuba. They brought the expedition's first prize: a small merchant ship filled with animal hides, sugar, and honey. The fleet then headed for the Bay of Honduras between July 7 and 10.

Attacking Honduras

The Dutch fleet saw the coast of Honduras on July 11. For the next three days, they carefully mapped the coastal waters. They made sure to stay hidden from the guards at the Santa Barbara Fortress.

On July 15, in the afternoon, the fleet's ships entered Trujillo's harbor. The fortress immediately started firing at the ships. Four sailors on the Zutphen ship were killed, which were the first losses for the expedition. Meanwhile, the smaller yachts and sloops went west of the city. They dropped off soldiers at the mouth of the Santo Antonio Creek. These soldiers marched east and quickly reached the fortress. They captured it after overpowering the Spanish defenders. With the fortress taken, the city was under Dutch control within two hours.

The Dutch soldiers rested in Trujillo that night. The next morning, they searched and looted the city's homes. In total, about 7 Dutch soldiers died, and 14 or 15 Spanish residents were killed.

According to a report from 1644 by Joannes de Laet, a director of the WIC, the city was looted on July 16. While the goods were being moved to the fortress, a fire started on the eastern side of the city. It quickly destroyed two-thirds of the buildings, which had roofs made of palm leaves. Some people died from burns when the gunpowder storage building caught fire. Whatever goods were left were loaded onto the ships the next day.

On July 19, van Hoorn made a deal with Juan de Miranda, the governor of Trujillo. He agreed to a ransom of twenty pounds of silver for the rest of the city. De Miranda told them that the Spanish had not known about their arrival until July 14. The ransom was paid, and the expedition left on July 21.

Attacking Campeachy

Van Hoorn's fleet had trouble sailing around the Yucatan Peninsula because their maps were not accurate. They saw Cozumel on July 25 and Cape Catoche on August 1, where they got fresh water. Here, they surprised an empty Spanish ship. From its crew, they learned that a Spanish naval group was looking for them. They also found out that Saint Martin, a Dutch salt-making station, had been captured by the Spanish.

Despite this news, they continued their journey. They saw Campeachy on the afternoon of August 11. The ships anchored about 12 to 15 miles (19 to 24 km) east-northeast of the city.

According to Laet's report, about 400 Dutch soldiers got into smaller boats. They anchored in shallower water to watch the city and get ready. On the morning of August 13, the soldiers landed on a beach about 1.5 miles (2.4 km) southwest of the city. They marched towards the city, protected by two boats that sailed alongside them and fired cannons at the Spanish defenders. The sloops Nachtegael and Gijsselingh also sailed along the coast and fired their weapons.

The Spanish infantry and cavalry defending the city were forced to run away. The Dutch quickly captured three trenches and entered the city. The defenders had set up defenses in the main plaza, but the Dutch attacked their barricades so fast that the Spanish cannons only fired once.

The Spanish defenders fought bravely, but only twenty prisoners were taken. While the Dutch loaded their loot onto captured boats, they tried to get a ransom from Governor Juan de Barros. He refused because a royal rule said he couldn't pay ransoms. On August 17, the Dutch left with their prisoners, nine captured ships, and anything else valuable they could find. They left the city buildings untouched because they were made of stone and hard to destroy. However, they burned the remaining Spanish ships and barges.

While moving the captured goods to their bigger ships, some Spaniards approached them. They bought back five of the captured ships and paid the ransom for the prisoners. The Dutch fleet then left on the morning of August 24.

Splitting Up and Returning Home

On September 18, the fleet was about 24 to 27 miles (39 to 43 km) south of Pan de Matanzas (a hill near Matanzas, Cuba). At this point, some of the crew wanted to continue looking for more prizes. So, the Otter and the sloops stayed behind. The rest of the fleet sailed to the open ocean through the Old Bahama Channel.

Under the command of Cornelis Jol, the Otter and the sloops Nachtegael and Gijsselingh were ordered to sail towards Cape San Antonio. They were to cruise along the southern coast of Cuba, heading for Tortuga. There, they would find out if the Spanish had captured St. Martin. After that, they were to do whatever was best for the Dutch West India Company.

According to Laet, on September 24, the ships fired at a Spanish galleon near Cabo Corrientes. On October 24, they captured a barge with 30 barrels of wine. In the first half of November, the Otter was pulled ashore for repairs. They learned from an Englishman that St. Martin had indeed been captured by the Spanish.

Back at sea, on the night of December 13–14, they saw about 15 ships and followed them. During the day, they saw one ship separated from the others and attacked it. They disabled its main sail and boarded it. Finding it carried only ballast (heavy material to stabilize a ship), they let it go. Two days later, they saw a fleet of 31 ships and followed from a distance. On December 19, they captured a small frigate, but it also had no cargo. They chased other Spanish ships but couldn't catch them. This smaller group of ships continued their journey and left the Caribbean on April 27, 1634. On June 6, they reached Texel, North Holland. The main part of the expedition had returned there earlier, on November 11, 1633. Jol's group brought back at least three captured ships.

What Happened Next

In late 1633, the governor of colonial Yucatan asked for money from local treasuries in the province. These funds came from settlements where Maya people had been forced to move. The governor said the money was extra, but he used it to strengthen Campeachy's defenses. It's thought that this money was needed partly because two Maya residents from the province had helped in the city's attack.

Fernando Centeno Maldonado, the governor of colonial Campeachy, lost his job in 1636. This was likely because van Hoorn had successfully attacked the city.

The loss of the Santa Barbara Fortress's cannons in Trujillo left the city very vulnerable. It remained poorly defended until late 1639, when the fortress finally received new weapons.

Lasting Impact

This expedition is believed to have helped weaken Spain's naval power in the Caribbean. Van Hoorn's capture of Campeachy, in particular, has been called "one of the most courageous acts committed by so few people" at that time. However, van Hoorn himself might have been disappointed because the expedition didn't bring a huge amount of money to the Dutch West India Company.

It has been suggested that van Hoorn's attack on Campeachy was so shocking to the people living there that it became a local legend. This story was romanticized over many generations. The event is a big part of El filibustero: Leyenda del siglo XVII, a novel written between 1841 and 1842 by Justo Sierra O'Reilly. This book tells the sad love story of Conchita from Campeachy and Diego el Mulato, who killed her father.

Some historians also believe that the two Maya pilots who helped the Dutch fleet participated in Campeachy's attack willingly. This is seen as an early example of how local Indigenous people in the 17th century resisted Spanish rule.

Images for kids