John Brown's last speech facts for kids

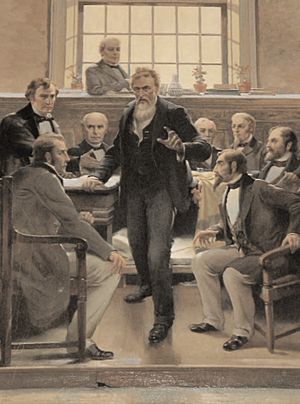

John Brown's last speech was given on November 2, 1859. This speech happened when John Brown was being sentenced in a courtroom in Charles Town, West Virginia. He had been found guilty of serious charges, including trying to free enslaved people by force. Many white people filled the courtroom to hear what he would say. Some people, like Ralph Waldo Emerson, thought this speech was as important as the famous Gettysburg Address.

John Brown spoke without notes, just as he usually did. But he had clearly thought a lot about what he wanted to say. A reporter wrote down every word, and the speech appeared on the front page of many newspapers the very next day. This included the New York Times.

People who wanted to end slavery, like the American Anti-Slavery Society, believed that if John Brown was executed, he would become a hero. They thought his death would inspire more people to fight against slavery.

Contents

What John Brown Said

In court, after someone is found guilty, they are asked if there is any reason why they should not be sentenced. When John Brown was asked this, he stood up right away. He spoke clearly and said:

I have, may it please the court, a few words to say.

In the first place, I deny everything but what I have all along admitted, the design on my part to free the slaves. I intended certainly to have made a clean thing of that matter, as I did last winter, when I went into Missouri and there took slaves without the snapping of a gun on either side, moved them through the country, and finally left them in Canada. I designed to have done the same thing again, on a larger scale. That was all I intended. I never did intend murder, or treason, or the destruction of property, or to excite or incite slaves to rebellion, or to make insurrection.

I have another objection; and that is, it is unjust that I should suffer such a penalty. Had I interfered in the manner which I admit, and which I admit has been fairly proved (for I admire the truthfulness and candor of the greater portion of the witnesses who have testified in this case), had I so interfered in behalf of the rich, the powerful, the intelligent, the so-called great, or in behalf of any of their friends, either father, mother, brother, sister, wife, or children, or any of that class, and suffered and sacrificed what I have in this interference, it would have been all right; and every man in this court would have deemed it an act worthy of reward rather than punishment.

This court acknowledges, as I suppose, the validity of the law of God. I see a book kissed here which I suppose to be the Bible, or at least the New Testament. That teaches me that "all things whatsoever I would that men should do to me, I should do even so to them" [Matthew 7:12]. It teaches me, further, to "remember them that are in bonds, as bound with them" [Hebrews 13:3]. I endeavored to act up to that instruction. I say, I am yet too young to understand that God is any respecter of persons. I believe that to have interfered as I have done as I have always freely admitted I have done in behalf of His despised poor, was not wrong, but right. Now, if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments, I submit; so let it be done!

Let me say one word further.

I feel entirely satisfied with the treatment I have received on my trial. Considering all the circumstances, it has been more generous than I expected. But I feel no consciousness of guilt. I have stated from the first [day] what was my intention and what was not. I never had any design against the life of any person, nor any disposition to commit treason, or excite slaves to rebel, or make any general insurrection. I never encouraged any man to do so, but always discouraged any idea of that kind.

Let me say, also, a word in regard to the statements made by some of those connected with me. I hear it has been stated by some of them that I have induced them to join me. But the contrary is true. I do not say this to injure them, but as regretting their weakness. There is not one of them but joined me of his own accord, and the greater part of them at their own expense. A number of them I never saw, and never had a word of conversation with, till the day they came to me; and that was for the purpose I have stated.

Now I have done.

In his speech, John Brown said his only goal was to free enslaved people. He mentioned a time he helped slaves escape from Missouri to Canada without violence. He claimed he wanted to do the same thing again, but on a larger scale. He denied wanting to commit murder or cause a big uprising.

Brown also argued that if he had helped rich or powerful people, his actions would have been praised. But because he helped the "despised poor" (enslaved people), he was being punished. He said his actions followed God's law, which teaches to treat others as you want to be treated. He also mentioned the Bible's teaching to "remember them that are in bonds." He believed what he did was right. He ended by saying he was ready to die if it helped bring justice to enslaved people.

He also stated he was happy with how his trial was handled. He felt no guilt and said he had always been clear about his intentions. He denied encouraging anyone to rebel and said people joined him willingly.

Courtroom Reaction

While John Brown spoke, the courtroom was completely silent. After his speech, the judge, Richard Parker, sentenced him to be hanged. This execution was set for December 2, one month later. The judge wanted the execution to be very public to serve as an example.

The courtroom remained quiet even after the death sentence was read. One person in the back cheered, but others quickly stopped him. People in the town were upset by this disrespectful behavior.

How the Speech Became Known

Many reporters were at John Brown's trial. Thanks to the new telegraph machine, they sent the speech out right away. The Associated Press shared it, and it appeared on the front page of newspapers like the New York Times the next day. Over the next few days, about 50 other newspapers across the country printed the full speech.

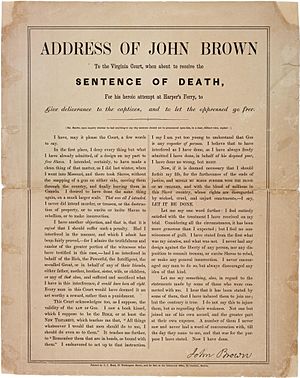

William Lloyd Garrison, a famous abolitionist, printed the speech as a large poster. He sold it from his newspaper office in Boston. The American Anti-Slavery Society also published it in a small book. On the cover, they put a Bible verse that said, "He, being dead, yet speaketh." This compared John Brown to Abel, a person in the Bible who was killed but whose story lived on.

First Reactions to the Speech

People Supporting John Brown

On December 1, the night before John Brown's execution, the abolitionist Wendell Phillips gave a speech in Brooklyn. He spoke at Henry Ward Beecher's church, which was a key place for people fighting against slavery and a stop on the Underground Railroad. Phillips's speech was a surprise, and he talked about John Brown.

Phillips said that John Brown was not just a rebel. He argued that the government of Virginia was wrong because it allowed slavery. Phillips called Virginia a "pirate ship" because it did not treat all its citizens equally. He believed John Brown was fighting for God and justice against this "pirate ship."

Frederick Douglass, another important abolitionist who had escaped slavery, also spoke out. He said that the government of Virginia was really just a group of people working against others.

In Boston, a group called the American Anti-Slavery Society decided to mark John Brown's execution. They saw it as the first step to making him a hero. They thought that if the governor had pardoned him, it would have taken away some of the power from the abolitionist movement.

People Against John Brown

Andrew Hunter, the Prosecutor

Andrew Hunter, who was the lawyer against John Brown in the trial, wrote about the speech 30 years later. He was surprised when Brown said his goal was not to start a slave uprising. Brown claimed he only wanted to help enslaved people escape to free states, like he had done in Kansas. Hunter noted that the speech was clearly well-planned and delivered slowly.

Rev. Samuel Leech, a Young Minister

A young minister named Samuel Leech felt that John Brown's statement was not fully true. He wondered why Brown had gathered so many weapons, like rifles and gunpowder. He also questioned why Brown and his men broke into the United United States Armory and Arsenal. They also shot people and held others hostage. However, Leech also said that everyone in the courtroom believed John Brown when he stated his only reason for acting was to free enslaved people.

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |