John Burland facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Burland

|

|

|---|---|

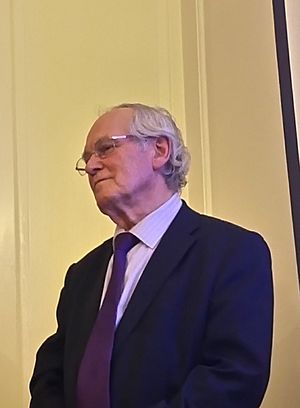

John Burland in Cambridge, 2016

|

|

| Born | 4 March 1936 Buckinghamshire, England

|

| Alma mater | Witwatersrand University University of Cambridge |

| Known for | Development of Critical state theory of soil mechanics Stabilisation of the Leaning Tower of Pisa |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Civil Engineering Soil Mechanics Geotechnical Engineering |

| Institutions | Ove Arup & Partners |

| Thesis | Deformation of soft clay (1967) |

| Doctoral advisor | Kenneth H. Roscoe |

John Boscawen Burland, born on March 4, 1936, is a famous geotechnical engineer. This means he is an expert in how soil and rocks behave. He is a professor at Imperial College London and a top expert in soil mechanics, which is the study of soil.

In 2016, he became a member of the National Academy of Engineering. This was because of his important work in designing, building, and protecting large structures and old buildings.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

John Burland was born in Buckinghamshire, England, in 1936. He moved to South Africa when he was a child. He went to Parktown Boys' High School.

He earned a degree in civil engineering from the University of the Witwatersrand in 1959. He then got his master's degree (MSc). His master's work showed that how we usually predict soil behavior needed changes. This was especially true for soil that was only partly wet.

In 1961, Burland came back to England. He started working for Ove Arup & Partners in London. There, he used his soil knowledge to help design Britannic House. This was London's tallest building at the time.

In 1963, Burland began his PhD at the University of Cambridge. He finished his studies in 1967. His research focused on how soft clay changes shape.

Amazing Engineering Projects

Burland joined the Building Research Station in 1966. He became the head of the Geotechnics Division in 1972. In 1980, he became a professor at Imperial College London. He led the Geotechnics Section for over 20 years.

He worked with another famous engineer, Alec Skempton. Burland even named Skempton's old office "Skem's Room." He also gave lectures at many universities.

Burland became well-known in the 1990s and early 2000s. He was one of the engineers who helped save the Leaning Tower of Pisa. For this work, he received special awards from Italy.

He also helped make sure the Houses of Parliament and Big Ben were safe. This was during the building of the London Underground Jubilee line extension. He also worked on a large underground car park at the Palace of Westminster. Another big project was stabilizing the Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral.

Saving the Leaning Tower of Pisa

The Leaning Tower of Pisa was in danger of falling. In March 1990, the Government of Italy asked Burland to join a team. This team had 14 members and their job was to save the tower. Burland worked on this project for 11 years.

He helped create a new way to fix the tower's lean. The goal was to make the tower stable for a long time. They wanted to do this without changing its historic look.

The tower sits on soft, squishy soil. It had been leaning more and more over hundreds of years. By the late 1900s, it was very close to falling. Burland realized that trying to strengthen the ground on the leaning side was too risky. It could make the tower collapse.

The team needed to fix the tower without making big, visible changes. Burland's plan included both temporary and lasting solutions. First, they put 900 tons of lead weights on the north side of the tower's base. This helped to temporarily stabilize it.

The permanent solution was to make the tower lean about 10 percent less. This would make the tower last much longer. They did this by carefully removing soil from under the north side of the tower. This method slowly and safely reduced the lean. It was a very clever way to fix the tower without damaging it.

Underground Car Park at Parliament

From 1972 to 1974, Burland worked on an underground car park. This car park was for Members of Parliament at Westminster. It was built very close to the historic Palace of Westminster. This included Westminster Hall and the Big Ben Clock Tower.

The design had to consider the soil very carefully. Burland studied samples of London Clay from the site. London Clay is good for digging deep holes. But it can change size depending on how much water is in it.

Burland found thin layers of silt and sand in the clay. These could cause water to flow through the soil. He made sure special steps were taken to prevent water from pushing up the car park floor. This was important during construction.

His team used computer models to understand how the ground would move. They also watched nearby buildings very closely. They checked the movement of walls and how much the ground lifted. They also checked if the Big Ben Clock Tower was still straight.

A strong concrete wall was built to keep the ground from moving too much. Construction started in July 1972 and finished in September 1974. The main digging happened successfully under Burland's guidance.

Teaching and Research

Burland has taught and researched many topics in geotechnical engineering. He studied how foundations affect buildings near big holes. He also looked at deep holes, tunnels, and different types of foundations. He researched how soil behaves when it's not fully wet.

Besides teaching at universities, Burland has appeared in the media. He helps explain soil mechanics to everyone. He was a special speaker at the 2023 Terzaghi Day. This event celebrates a famous engineer named Karl von Terzaghi.

Critical State Soil Mechanics

Burland's PhD research was on critical state soil mechanics. This is a way to understand how soil changes under stress. He improved an existing model for clay. This led to his own model, called the Modified Cam-Clay Model.

Awards and Honors

John Burland has received many awards for his work. He was invited to give the 30th Rankine Lecture. This is a very important lecture in geotechnical engineering. He also received the Gold Medal from the Institution of Structural Engineers in 1997.

He was made a Fellow of the Royal Academy of Engineering. In 2005, he was awarded the Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE). This was for his services to engineering. He also received honorary degrees from several universities. In 2006, he won the Rooke Award. This was for helping people learn about engineering.

His awards include:

- Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (CBE), 2005

- Honorary Fellow of Cardiff University, 2005

- Fellow (FIC), Imperial College, 2004

- Honorary Fellow, Emmanuel College Cambridge, 2004

- "Commendatore" of the "Ordine della Stella di Solidariete' Italiana" (OSSI), President of Italy, 2003

- DSc Honoris Causa, University of Warwick, 2003

- DEng Honoris Causa, University of the Witwatersrand

- "Commendatore" of the Royal Order of Francis I of Sicily (KCFO), 2001

- DEng Honoris Causa, University of Glasgow, 2001

- DSc Honoris Causa, University of Nottingham, 1998

- Fellow (FCGI), City and Guilds of London Institute, 1998

- Fellow (FRS), The Royal Society, 1997

- DEng Honoris Causa, Heriot-Watt University, 1994

- Fellow (FREng), Royal Academy of Engineering, 1981.

See also

- Imperial College Civil & Environmental Engineering

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |