John Doubleday (restorer) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Doubleday

|

|

|---|---|

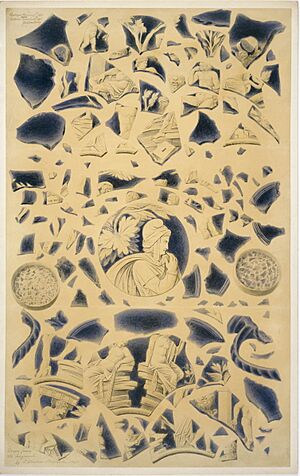

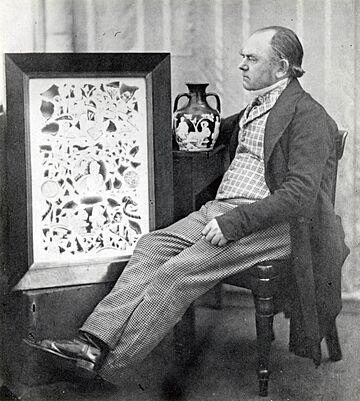

John Doubleday around 1845 with his restoration of the Portland Vase, and a watercolour of the shattered fragments

|

|

| Born | About 1798 New York, U.S.

|

| Died | 25 January 1856 |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | Restorer, dealer |

| Years active | 1836–1856 |

| Known for | Reconstructing the Portland Vase |

| Signature | |

John Doubleday (born around 1798 – died 25 January 1856) was a skilled British craftsperson and restorer. He also bought and sold old items. For the last 20 years of his life, he worked for the famous British Museum.

John Doubleday had many jobs at the museum. His main role was being a specialist restorer. He might have been the very first person to hold such a job there. He is most famous for fixing the Portland Vase in 1845. This ancient Roman vase was badly broken, and his repair was amazing for its time.

Besides his museum work, Doubleday also sold copies of old coins, medals, and ancient seals. He made these copies from materials like colored sulphur and white metal. This allowed smaller collections to own copies that looked very real, but cost much less than the originals. Thousands of his copies were bought by museums and people. Sometimes, his copies were so good that they were mistaken for the real thing!

Not much is known about John Doubleday's early life. Records show he was born in New York, U.S., but became a British citizen. An old newspaper mentioned that he worked in a printer's shop for over 20 years when he was young. This job taught him how to cast metal, which was useful for making his famous copies later on. He died in 1856 and had a wife and five daughters.

Contents

Working at the British Museum

From 1836 to 1856, John Doubleday worked in the Department of Antiquities at the British Museum. He seemed to work as a freelance expert. This meant he was hired for specific tasks and sometimes helped the museum buy items.

He also gave many valuable items to the museum. For example, in 1830, he donated 2,433 copies of medieval seals. This was the most important donation the museum received that year! He also gave coins and more copies of seals in the following years. In 1836, he even gave the museum a picture of himself. His gifts of seal copies were still considered very important many years later.

Doubleday was likely the museum's main restorer, and possibly the first person to have this job. When he died, people said his position was left empty. They noted that he was "chiefly employed in the repair of countless works of art." Everyone agreed that no one else could have done these delicate repairs with such skill and patience. He was seen as one of the most valuable people working in that department.

Restoring the Portland Vase

A very important moment in Doubleday's career happened on February 7, 1845. On that day, a young man accidentally smashed the famous Portland Vase. This ancient Roman vase, made of cameo glass, broke into hundreds of pieces. It was one of the most well-known glass objects in the world.

John Doubleday was chosen to fix it. First, he asked an artist named Thomas H. Shepherd to paint a picture of all the broken pieces. We don't know exactly how Doubleday put the vase back together. But on May 1, he talked about his work to a group of experts. By September 10, he had glued the vase back into one piece!

Only 37 tiny splinters were left out, mostly from the inside of the vase. The original base disc was found to be a newer replacement, so it was displayed separately. Doubleday made a new, plain glass base for the vase. He even engraved it with a diamond, saying: "Broke Feby 7th 1845 Restored Sept 10th 1845 By John Doubleday." The British Museum was so impressed that they gave him an extra £25 for his amazing work.

At the time, people called his restoration "masterly." One magazine praised his "skilful ingenuity" and "cleverness." They even said it was enough to make him "the prince of restorers." Even in 2006, an expert from the museum said Doubleday's achievement put him "in the forefront of the craftsmen-restorers of his time." Doubleday's repair lasted for over 100 years. The vase was later restored two more times, in 1948–1949 and in 1988–1989.

Other Important Work

Besides the Portland Vase, John Doubleday did other important work at the British Museum. In 1851, he successfully fixed some bronze bowls from Nimrud. Another restorer had used acid to clean them, which caused a lot of damage. Doubleday used a "very simple process" without acids to fix them. We don't know his exact method, but it might have involved warm water and soap.

Doubleday was also asked to help with clay tablets from Babylonia and Assyria. These tablets arrived at the museum between 1850 and 1855. Some were poorly packed and had developed white crystals, making the writing hard to read. Doubleday tried to remove these crystals.

He first tried to make the tablets harder by heating them in a kiln, like making pottery. But this caused the surfaces to flake off, damaging the writing. His second idea was to soak the tablets in liquids. This also caused them to fall apart. So, the museum stopped these efforts. Even though his attempts failed, his ideas were ahead of his time. Later, other experts used similar methods more successfully. Doubleday is seen as the inventor of this method, and his failures might have been because he changed the temperature too quickly.

Selling and Copying Old Items

Apart from his work at the British Museum, Doubleday was also a dealer and a skilled copyist. He made copies of coins, medals, and ancient seals. He sold these copies from his shop, which was located near the British Museum. This closeness might have helped him get his job at the museum.

He sold copies made from sulphur, which he colored in different shades. He also used white metal. He sold other interesting items too, like old cabinets and snuff boxes. He even sold pieces of wood said to be from a tree planted by Shakespeare!

In 1835, Doubleday advertised that he had copies of 6,000 Greek coins, and many Roman coins and medallions for sale. He also had "the most extensive Collection of Casts in Sulphur of ancient seals ever formed." By 1851, he had copies of over 10,000 seals. When he died, people said he had the largest collection of seal copies in England, and perhaps even the world.

Because his collection was so complete, he helped create a detailed list of Roman coins related to Britain in a book called Monumenta Historica Britannica. Doubleday was on good terms with many museums and collectors. This allowed him to make copies from important collections, including those at the British Museum and the National Library of France in Paris.

Doubleday's copies were not expensive and were sold widely. He was well-known among collectors. Even universities, like University College London, bought his copies to complete their collections. They found them to be good, affordable substitutes for studying. Because his copies looked so real, some were later mistaken for original items. One book from 1904 even called Doubleday a forger, but added that it was "open to doubt" whether he meant to trick collectors. Later editions of the book removed this claim.

About His Life

We don't know much about John Doubleday's personal life or how he grew up. An old book from 1859 said he was American. The 1851 census recorded him as an "artist" born in New York, but a British citizen. He was married to a woman named Elizabeth and had five daughters, all born in London. His oldest daughter, also named Elizabeth, was born around 1833. This suggests he and his wife were married by then.

According to an old newspaper, Doubleday worked in a printer's shop for over 20 years when he was young. This job taught him how to make type for printing, which gave him skills in casting metal and other materials. After that, he started making copies of medals, ancient seals, and coins. He even invented new ways to do this. He also made castings for the Royal Mint and helped start the Royal Numismatic Society, which is a group for coin collectors. By 1832, he was listed in business directories as a dealer in "Curiosity, shell & picture dealers" and ancient seals. Besides his museum work, he might have been a collector himself.

John Doubleday died on January 25, 1856, after being sick for a long time. He was about 57 years old. His colleagues said his illness was "extreme," and he couldn't be reached for months. Newspapers like The Athenæum and The Gentleman's Magazine published news of his death. He was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery. His library of books was sold by Sotheby's that April, earning £228.

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |