Joseph B. Soloveitchik facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Joseph B. Soloveitchik |

|

|---|---|

Official photograph from Yeshiva University

|

|

| Religion | Judaism |

| Denomination | Orthodox Judaism |

| Personal | |

| Nationality | American |

| Born | February 27, 1903 12 Adar 5663 Pruzhany, Grodno Governorate, Russian Empire (present-day Belarus) |

| Died | April 9, 1993 (aged 90) Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America |

| Spouse | Tonya Lewit, Ph.D. (1904-1967) |

| Parents | Moshe Soloveichik and Peshka Feinstein Soloveichik |

| Senior posting | |

| Title | The Rav |

| Position | Rosh yeshiva |

| Yeshiva |

|

| Yahrtzeit | 18 Nissan 5753 |

| Buried | Beth El Cemetery, West Roxbury, Massachusetts, USA |

| Dynasty | Soloveitchik dynasty |

Joseph Ber Soloveitchik (Hebrew: יוסף דב הלוי סולובייצ׳יק Yosef Dov ha-Levi Soloveychik; February 27, 1903 – April 9, 1993) was a very important American Orthodox rabbi. He was also a great Talmud scholar and a modern Jewish thinker. People often called him The Rav. He came from a famous family of rabbis, the Soloveitchik dynasty, known for their deep Torah study.

He was a rosh yeshiva (head of a yeshiva) at Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary (RIETS) in Yeshiva University in New York City. Over nearly 50 years, he ordained almost 2,000 rabbis. Many people in Modern Orthodox Judaism looked up to him. He was a guide and role model for thousands of Jews.

Contents

His Family Background

Joseph Ber Soloveitchik was born on February 27, 1903. This was in Pruzhany, which was part of Imperial Russia then. Today, it is in Belarus. His family had been rabbis for about 200 years. His grandfather was Chaim Soloveitchik. His great-grandfather, who he was named after, was Yosef Dov Soloveitchik.

His father, Moshe Soloveichik, was also a respected rabbi. He was the head of the RIETS before Joseph Ber Soloveitchik. His mother, Pesha, was related to another famous rabbi, Rav Moshe Feinstein.

His Early Life and Education

Joseph Ber Soloveitchik had a traditional Jewish education. He went to a Talmud Torah and an elementary yeshiva. He also had private teachers because his parents saw how smart he was. In 1922, he finished high school in Dubno. He then studied political science at the Free Polish University in Warsaw in 1924.

In 1926, he moved to Berlin, Germany. There, he went to the Friedrich Wilhelm University. He studied philosophy, economics, and Hebrew subjects. At the same time, he kept up his intense Talmud studies. He learned from important European philosophers. He also studied the ideas of Immanuel Kant.

He wrote his Ph.D. paper on the ideas of the German philosopher Hermann Cohen. He earned his doctorate degree in December 1932. In 1931, he married Tonya Lewit. She also had a Ph.D. in Education.

During his time in Berlin, Soloveitchik became a student of Chaim Heller. He also met other young scholars. These included Yitzchak Hutner. Both of them helped connect traditional Jewish learning with modern ideas.

Moving to America

In 1932, Soloveitchik moved to America. He settled in Boston and was known as "The Soloveitchik of Boston." He started a yeshiva there called Heichal Rabbeinu Chaim HaLevi. It was also known as the Boston Yeshivah.

In 1937, he started the Maimonides School. This was one of the first Hebrew day schools in Boston. When the high school opened, he made an important change. He taught Talmud to both boys and girls in the same classes. He also helped with many religious issues in Boston. He gave lectures on Jewish and religious philosophy at colleges.

Teaching in New York

In 1941, Soloveitchik took over from his father. He became the head of the RIETS rabbinical school at Yeshiva University. He taught there until 1986. He was seen as the main Rosh Yeshiva until he passed away in 1993.

He gave ordination to over 2,000 rabbis. Many of them became leaders in Orthodox Judaism. He also gave public lectures that thousands of people attended. He encouraged more intense Torah study for Jewish women. He taught the first Talmud class at Stern College for Women. He inspired many young people to become Jewish leaders and teachers.

His Ideas and Books

Rabbi Soloveitchik wrote many important essays and books. These changed how people thought about Jewish philosophy and Jewish theology. He always focused on the importance of halakha, which means Jewish law.

Torah Umadda: Combining Knowledge

While at Yeshiva University, Rabbi Soloveitchik developed an idea called "synthesis." This meant combining the best of religious Torah learning with the best of modern, secular knowledge. This idea became known as Torah Umadda. It means "Torah and secular wisdom." This is the motto of Yeshiva University.

Some people, like his brother Rav Ahron Soloveichik, had different views. They said that while he valued worldly knowledge, he didn't see it as a main part of Judaism itself. They believed he used his worldly knowledge to help him understand and teach Torah better.

Through his lectures and writings, Rabbi Soloveitchik helped shape Modern Orthodox Judaism. His books offered a unique way of combining modern ideas with Jewish thought.

The Lonely Man of Faith

In his book The Lonely Man of Faith, Rabbi Soloveitchik looked at the first two chapters of Genesis. He saw two types of human beings there:

- Adam I is the "majestic man." This person uses their creativity to control their surroundings. They want to master the world and make it better. This Adam is about achieving and building.

- Adam II is the "covenantal man." This person gives themselves over to God. They seek a deeper meaning in life and connection with others. This Adam is about faith and community.

Rabbi Soloveitchik explained how a person of faith can bring both of these parts together. They can be creative and achieve things, while also having deep faith and connection.

Halakhic Man

In Halakhic Man, Rabbi Soloveitchik wrote about how important halakha is in Jewish thought. He said that following Jewish law is the main way to practice Judaism. He believed that Jewish law is the foundation for Jewish thought and practice. He showed how a person who studies Torah and follows the commandments develops a special way of thinking about life. This includes ideas about learning, self-control, death, and creativity.

Some scholars, like Abraham Joshua Heschel, disagreed with this idea. Heschel felt that Judaism also has a lot of emotion and heart, not just logic. He said that a "Halakhic Man" might not fully capture the richness of Jewish life. He preferred the term "Ish Torah" (Torah man), which includes both Jewish law and deeper spiritual ideas.

Halakhic Mind

His book Halakhic Mind looks at how science and philosophy have connected throughout history. In the last part, he discusses how these ideas relate to Halakha.

His Family and Later Years

In the 1950s and 1960s, Rabbi Soloveitchik spent summers near Cape Cod in Onset, Massachusetts. He would pray at Congregation Beth Israel with some of his students.

After his wife passed away in 1967, he started giving more public lectures in Boston during the summers.

His daughters married important scholars. His daughter Tovah married Aharon Lichtenstein, who was also a Rosh Yeshiva. His daughter Atarah married Isadore Twersky, who led the Jewish Studies department at Harvard University. His son Haym Soloveitchik is a professor of Jewish History at Yeshiva University. His grandchildren also hold important scholarly positions.

As he grew older, he faced serious illnesses like Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease.

His Works

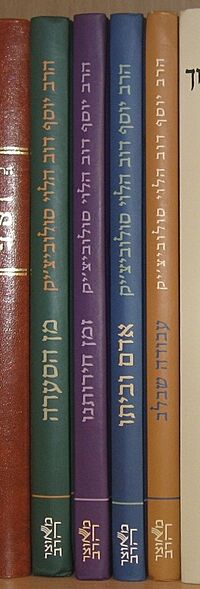

Here are some of the books and essays written by Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik:

- Halakhic Morality: Essays on Ethics and Mesorah

- Confrontation and Other Essays

- The Lonely Man of Faith

- Halakhic Man

- The Halakhic Mind

- Fate and Destiny: From Holocaust to the State of Israel

- Family Redeemed: Essays on Family Relationships

- Out of the Whirlwind: Essays on Mourning, Suffering and the Human Condition

- Worship of the Heart: Essays on Jewish Prayer

- Emergence of Ethical Man

- Community, Covenant and Commitment - Selected Letters and Communications

- Festival of Freedom: Essays on Pesah and the Haggadah

- Kol Dodi Dofek

- The Lord is Righteous in All His Ways: Reflections on the Tish'ah Be'Av Kinot

- Days of Deliverance: Essays on Purim and Hanukkah

- Abraham's Journey: Reflections on the Life of the Founding Patriarch

- Vision and Leadership: Reflections on Joseph and Moses

- And From There You Shall Seek (U-Vikkashtem mi-Sham)

- On Repentance (Hebrew "Al haTeshuva")

Awards

- 1985: National Jewish Book Award for Halakhic Man

- 2010: National Jewish Book Award for The Koren Mesorat HaRav Kinot

See also

- Jewish existentialism

- Maimonides School, the school founded by Soloveitchik in Brookline

- Yeshiva University

Images for kids