Katz v. United States facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Katz v. United States |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Argued October 17, 1967 Decided December 18, 1967 |

|

| Full case name | Charles Katz v. United States |

| Citations | 389 U.S. 347 (more)

88 S. Ct. 507; 19 L. Ed. 2d 576; 1967 U.S. LEXIS 2

|

| Prior history | 369 F.2d 130 (9th Cir. 1966); cert. granted, 386 U.S. 954 (1967). |

| Holding | |

| The Fourth Amendment's protection from unreasonable search and seizure extends to any area where a person has a "reasonable expectation of privacy." | |

| Court membership | |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Stewart, joined by Warren, Douglas, Harlan, Brennan, White, Fortas |

| Concurrence | Douglas, joined by Brennan |

| Concurrence | Harlan |

| Concurrence | White |

| Dissent | Black |

| Marshall took no part in the consideration or decision of the case. | |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. amend. IV | |

|

This case overturned a previous ruling or rulings

|

|

| Olmstead v. United States (1928) | |

Katz v. United States was a very important decision by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1967. This case changed how the Court understood what counts as a "search" or "seizure" under the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. The Fourth Amendment protects people from unfair searches and seizures by the government.

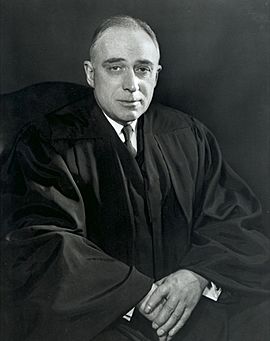

After this decision, the Fourth Amendment's protections grew. It now covers not just a person's belongings or home, but also any place where a person has a "reasonable expectation of privacy." This idea, called the Katz test, was explained by Justice John Marshall Harlan II. The Katz test has been used in many cases, especially as new technologies create new questions about privacy.

Contents

What Was the Katz Case About?

Charles Katz was a person involved in sports betting. In 1965, he was using a public telephone booth in Los Angeles, California. He was calling people in Boston and Miami to share information about his betting predictions.

Unknown to Katz, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) was watching him. They placed a hidden listening device on the outside of the phone booth. They recorded many of his phone calls. After gathering this information, FBI agents arrested Katz. They accused him of breaking a federal law by sharing illegal betting information over the phone between states.

The Court Cases Before the Supreme Court

Katz was tried in a U.S. District Court. His lawyer asked the court not to use the FBI's recordings as proof. The lawyer argued that the FBI agents did not have a search warrant to place their listening device. This meant the recordings were taken against the Fourth Amendment.

However, the judge did not agree and allowed the recordings to be used. Katz was found guilty based on these recordings.

Katz then appealed his case to a higher court, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. In 1966, this court agreed with the first judge. They said that because the FBI's device did not physically go inside the phone booth, it was not a "search." So, the FBI did not need a search warrant.

Katz then asked the U.S. Supreme Court to hear his case, and they agreed. The Supreme Court heard arguments from both sides in October 1967.

The Supreme Court's Decision

On December 18, 1967, the Supreme Court made its decision. They ruled 7–1 in favor of Katz. This decision meant the FBI's wiretap was not allowed, and Katz's conviction was overturned.

The Court's Main Opinion

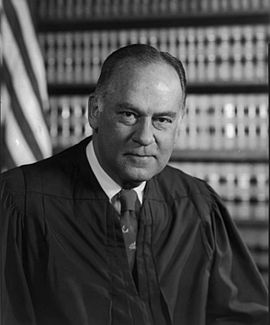

Seven justices agreed with the main opinion, which was written by Justice Potter Stewart. The Court said that the case was not just about whether the phone booth was a "protected area" or if the FBI physically went inside it. Instead, the Court looked at how Katz used the phone booth and what he expected.

Justice Stewart wrote a famous part of the opinion:

The Fourth Amendment protects people, not places. What a person knowingly shows to the public, even in his own home or office, is not protected by the Fourth Amendment. But what he tries to keep private, even in a public area, may be protected.

The Court explained that American courts used to think about Fourth Amendment searches like a physical trespass. They looked at an older case from 1928, Olmstead v. United States. In that case, the Court had said that wiretapping without physically entering a place was not a search.

However, the Court in Katz said that the law had changed. They stated that the old idea of "trespass" was no longer the main rule. The Court concluded:

The Government's actions in electronically listening to and recording [Katz's] words violated the privacy on which he reasonably relied while using the telephone booth. This was a "search and seizure" under the Fourth Amendment.

Justice Stewart finished by saying that even though the FBI thought Katz was breaking the law, their wiretap was unconstitutional. This was because they did not get a search warrant before placing it.

Justice Harlan's Important Concurring Opinion

Justice John Marshall Harlan II wrote a separate opinion that agreed with the main decision. His opinion has become very well-known. It described a two-part test, now called the "Katz Test."

Harlan explained that he understood the main opinion to mean that the Fourth Amendment protects privacy when a person expects privacy, and when society agrees that this expectation is reasonable. He summarized his idea with a two-part test:

First, a person must have shown an actual expectation of privacy. Second, that expectation must be one that society is ready to recognize as "reasonable."

For example, a person usually expects privacy in their home. But things they show openly to others are not protected. Also, conversations in public would not be protected, because expecting privacy in that situation would not be reasonable.

The Supreme Court later officially adopted Harlan's two-part test in a 1979 case called Smith v. Maryland.

Justice Black's Disagreement

Justice Hugo Black was the only justice who disagreed with the decision. He argued that the Fourth Amendment was only meant to protect physical "things" from searches and seizures. He believed it was not meant to protect personal privacy.

Black also said that wiretapping was similar to eavesdropping, which existed when the Bill of Rights was written. He thought that if the people who wrote the Fourth Amendment wanted it to protect against eavesdropping, they would have said so clearly.

How the Katz Decision Changed Things

The Supreme Court's decision in Katz greatly expanded the protections of the Fourth Amendment. It changed how American courts looked at searches and seizures. Many police actions that were not previously covered by the Fourth Amendment, like wiretaps on public phone lines, now are. This means law enforcement usually needs a search warrant first.

However, Katz also made applying the Fourth Amendment more complicated. The "reasonable expectation of privacy" test, which is used by many U.S. courts, has been harder to use than the old idea of a physical trespass.

In a 2007 article, legal expert Orin Kerr explained that even after many years, the meaning of "reasonable expectation of privacy" is still not completely clear. He noted that many scholars believe the Supreme Court's cases on this topic have been difficult to understand.

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |