Serjeant-at-law facts for kids

Imagine a very old and important group of lawyers in England and Ireland. They were called Serjeants-at-Law, or just Serjeants. This special group was made up of top barristers, who are lawyers that argue cases in court.

The Serjeants were around for centuries, even before the year 1300! Some people think they came from similar lawyers in France. They were considered the oldest official legal group in England. For a long time, they were a small, powerful team. They handled many important cases in the main courts.

But over time, things changed. New types of lawyers, like "Queen's Counsel," started to appear. These new roles slowly made the Serjeants less unique. By the 1800s, their special powers were gone. The last Serjeant was appointed in 1873. His name was Nathaniel Lindley. He later became a very important judge. The last Irish Serjeant was A. M. Sullivan, appointed in 1912.

Contents

What Was a Serjeant-at-Law?

For many years, Serjeants had special rights in a court called the Court of Common Pleas. They were the only lawyers allowed to argue cases there! They could also speak in other important courts. Serjeants were more important than other lawyers.

Only Serjeants could become judges in these main courts until the 1800s. They even ranked higher than some knights! There were different kinds of Serjeants. The King's Serjeants were special lawyers who advised the King. The King's Premier Serjeant was the King's favorite. The King's Ancient Serjeant was the oldest.

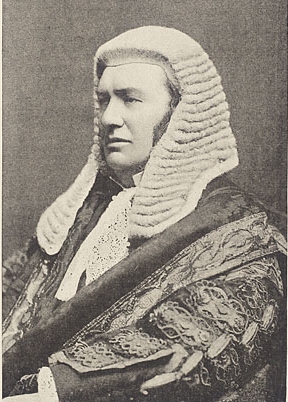

Serjeants wore special clothes. The most famous part was the coif. This was a white cap, like a skullcap. Later, they wore a small black patch over it. When wigs became popular, Serjeants had a small white and black patch on their wigs.

A Look Back: The History of Serjeants

How Old Are the Serjeants?

The Serjeants-at-Law have a very long history. Some experts believe they existed even before the Normans came to England in 1066. They might have come from lawyers in Normandy, France. They were sometimes called "Serjeant-Conteurs."

Early Serjeants met near St Paul's Cathedral in London. They would give legal advice to people there. A famous writer, Geoffrey Chaucer, even wrote about a Serjeant in his book, Canterbury Tales.

We have clear proof of Serjeants in England from the 1200s. This makes them the oldest royal legal group. The next oldest is the Order of the Garter, created in 1330. By the late 1200s, there were about 20 to 36 Serjeants. Rules were made to stop Serjeants from misbehaving.

In the 1320s, Serjeants slowly gained exclusive rights in the Court of Common Pleas. This meant only they could argue cases there. From then on, new Serjeants were usually appointed in groups.

When Serjeants Were Most Powerful

In the 1500s, Serjeants-at-Law were a small but very respected group. There were usually fewer than ten of them alive at any time. Sometimes, there was only one! Over 100 years, only 89 new Serjeants were created.

They were the only clear group of legal professionals back then. In fact, their work might have helped create barristers as a separate group. Serjeants usually argued cases themselves. But sometimes, they let other lawyers help them. These helpers were called "outer" or "utter" barristers. If they helped, it meant they had "passed the bar" and were on their way to becoming a Serjeant.

Even though they had a monopoly in the Common Pleas court, Serjeants also handled most cases in the Court of King's Bench. They were supposed to work mainly in the Common Pleas. But some Serjeants worked elsewhere, like Robert Mennell, who stayed in Northern England.

This was a successful time for Serjeants as judges. Since only Serjeants could become judges in the main courts, many also served in the Exchequer of Pleas. However, other courts started to grow. This allowed other lawyers to gain experience. This slowly took work away from the Serjeants. Also, the few Serjeants couldn't handle all the cases in the Common Pleas. This helped barristers become dedicated court lawyers.

Why Serjeants Disappeared

The decline of the Serjeants-at-Law began in 1596. Francis Bacon convinced Queen Elizabeth I to make him "Queen's Counsel Extraordinary." This new role gave him higher rank than the Serjeants. In 1604, King James I made this role official.

At first, only a few Queen's (or King's) Counsel were created. But after the English Restoration, more and more were appointed each year. By the time of King William IV, about nine were appointed yearly. Later, around 12 were created each year.

Every new Queen's Counsel made the Serjeants less important. Even the newest Queen's Counsel ranked higher than the oldest Serjeant. The rule that all judges must be Serjeants was also bypassed. People chosen to be judges were simply made Serjeants right before becoming judges.

In 1834, Lord Brougham tried to open up the Court of Common Pleas to all barristers. The Serjeants fought this and got it overturned. But their special status didn't last long.

In 1846, a law called the Practitioners in Common Pleas Act 1846 allowed all barristers to work in the Common Pleas. The final blow came with the Judicature Act 1873, which started in 1875. This law said that judges no longer had to be Serjeants. With this, and the rise of Queen's Counsel, there was no longer a need for Serjeants. The practice of appointing them ended.

The last English Serjeant who argued cases, Frederick Lowten Spinks, died in 1899. The very last English Serjeant was Nathaniel Lindley, Baron Lindley. He was made a Serjeant only so he could become a judge. He died in 1921.

The Irish Serjeants lasted a bit longer, until 1919. The last Irish Serjeant, Alexander Sullivan, moved to England. He was still called "Serjeant Sullivan" out of respect.

How Serjeants Lived and Worked

Serjeant's Inn: Their Special Home

Serjeant's Inn was a special place just for Serjeants-at-Law. It was like a private club for them. They had three locations over time. One was in Holborn, then Fleet Street, and finally Chancery Lane. The Inn on Chancery Lane was torn down in 1877.

Joining the Inn was not required, but most Serjeants did. There were usually fewer than 40 Serjeants, including judges. The Inns were much smaller than the famous Inns of Court.

The Inn on Fleet Street was used from at least 1443. It was rebuilt after the Great Fire of London in 1666. But it was abandoned in 1733 because it was falling apart.

The Chancery Lane Inn had a large hall, dining room, and library. New Serjeants had to pay a lot of money to join. The hall was decorated with portraits of famous judges and Serjeants. It also had their family coats of arms. When the Fleet Street Inn closed, Chancery Lane became the only home for Serjeants. After the Serjeants order ended in 1873, there was no way to support the Inn. It was sold in 1877. The remaining Serjeants were welcomed into their old Inns of Court.

Becoming a Serjeant: The Call to the Coif

The process of becoming a Serjeant-at-Law stayed mostly the same for a long time. Serjeants would suggest new candidates. These names went to the Chief Justice, then to the Lord Chancellor, who would make the appointments. This system helped choose good judges.

Serjeants were appointed by a special order from the King. This order told them to "take the state and degree of a Serjeant-at-Law." The new Serjeants would gather in an Inn of Court. They would hear a speech and receive a purse of gold. Then, the coif (their special cap) was placed on their head.

Serjeants had to take an oath. They promised to:

- Serve the King's people.

- Give true advice to those who hired them.

- Not delay cases for money or profit.

- Always be present when needed.

New Serjeants would hold a big feast to celebrate. They gave rings to friends, family, the King, and other important people. The main courts would even close for the day! The feasts were so big that they were held in large places like Ely Place. Over time, the feasts became smaller. The last one was in 1736.

What Serjeants Wore

A Serjeant-at-Law's traditional clothes included a coif, a robe, and a furred cloak. The robe and cloak later became part of what judges wear. The color of the robes changed over time. Records show judges and Serjeants wearing scarlet, green, purple, and brown. By the end, the formal robes were red. But for everyday court work, black silk gowns were common. The red robe was only for special events.

The cape was a separate cloak at first. It later became part of the uniform. It was different from a judge's cape because it was lined with lambskin fur. Serjeants did not wear their capes into court.

The coif was the most important symbol of the Serjeants. It's why they were sometimes called the "Order of the Coif." The coif was white and made of silk or fine cloth. A Serjeant never had to take off or cover his coif, not even in front of the King. The only exception was when a judge passed a death sentence. Then, he would wear a black cap over the coif.

When wigs became popular for lawyers, it was tricky for Serjeants. They couldn't cover their coif. So, wigmakers added a small white cloth to the top of the wig to represent the coif. A small black piece of cloth was worn over the white part. This represented the black skullcap Serjeants started wearing in the 1300s.

King's or Queen's Serjeants

A King's or Queen's Serjeant was a special Serjeant-at-Law. They advised the King or Queen and their government. They were like the Attorney-General for England and Wales. King's Serjeants represented the Crown in court. They acted as prosecutors in criminal cases. They also represented the government in civil cases. They had higher power in lower courts than the Attorney-General.

King's Serjeants also advised the House of Lords. They were not allowed to work on cases against the Crown. They couldn't do anything that would harm the King or Queen. For example, in 1540, Serjeant Browne was punished for creating a tax avoidance plan.

King's Serjeants wore a black coif with a thin white strip. Regular Serjeants had an all-white coif. King's Serjeants took a second oath. They promised to serve "The King and his people," not just "The King's people." The King's favorite Serjeant was called the King's Premier Serjeant. The oldest was the King's Ancient Serjeant.

Their Special Status and Rights

For most of their history, Serjeants and King's Serjeants were the only lawyers allowed to speak in the Court of Common Pleas. Until the 1600s, they were also the highest-ranking lawyers in the Court of King's Bench and Court of Chancery. This gave them priority in court motions.

Serjeants also had special protection from most lawsuits. They could only be sued by a special order from the Court of Chancery. Their servants also had this protection. Serjeants also performed some judge-like duties in the Common Pleas.

In return for these privileges, Serjeants had duties. They had to represent anyone who asked, even if they couldn't pay. Also, because there were few judges, Serjeants often served as temporary judges.

Only Serjeants-at-Law could become judges in the main common law courts. This rule started in the 1300s. It was later extended to the Exchequer of Pleas in the 1500s. It did not apply to the Court of Chancery or church courts.

Serjeants-at-Law also had social privileges. They ranked higher than some knights. Their wives could even be called "Lady." Serjeants earned higher fees than regular barristers.

King's Serjeants ranked above all other barristers, even the Attorney-General. This changed over time. In the 1600s, a royal order gave the Attorney-General higher rank than most King's Serjeants. By 1814, the Attorney-General was made superior to all King's Serjeants. This remained until the Serjeants-at-Law order ended.

Serjeants in Stories

The main character in C. J. Sansom's Shardlake novels is a Serjeant-at-Law. His name is Matthew Shardlake. He is a hunchback lawyer who lives during the time of King Henry VIII of England.