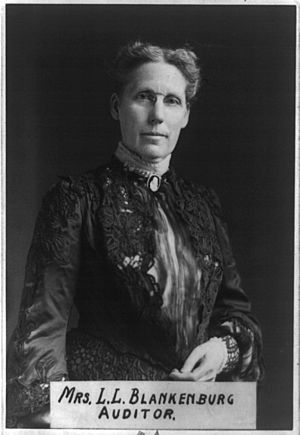

Lucretia Longshore Blankenburg facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Lucretia Longshore Blankenburg

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Lucretia Longshore

May 8, 1845 On a farm near New Lisbon, Ohio

|

| Died | March 28, 1937 (aged 91) |

| Other names | Mrs. Rudolph Blankenburg |

| Occupation | Suffragist, social activist, civic reformer, and writer |

| Spouse(s) | Rudolph Blankenburg |

Lucretia Longshore Blankenburg (born May 8, 1845 – died March 28, 1937) was an important American leader. She fought for women's right to vote, worked to improve society, and helped make cities better places. She was also a writer.

From 1892 to 1908, Lucretia was the president of the Pennsylvania Woman Suffrage Association. This group worked hard to get women the right to vote. Her husband, Rudolph Blankenburg, later became the mayor of Philadelphia. Together, they worked to make politics cleaner and to help people become better citizens. Lucretia often helped her husband with speeches and handled much of his mail.

She was a leading figure in women's clubs. She served as vice-president of the National Education Association and the General Federation of Women's Clubs. She was also a member of the New Century Club and the Civic Club. Lucretia spoke many times to the Pennsylvania General Assembly (the state's law-making body). She also spoke in the House of Representatives and the Senate to support laws for women.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Lucretia Longshore was born on May 8, 1845, on a farm near New Lisbon, Ohio. Her mother, Dr. Hannah Longshore, was one of the first women doctors. Her father, Thomas Ellwood Longshore, was a Quaker school teacher. Lucretia was named after Lucretia Mott, a famous woman who also fought for women's rights.

When Lucretia was six months old, her family moved to Attleboro, Pennsylvania (now Langhorne, Pennsylvania). Five years later, they moved to Philadelphia. This move allowed her mother to attend medical school. Hannah Longshore graduated from the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania in its first class.

Lucretia attended the Friend's Central School in Philadelphia. She faced challenges from other children who sometimes teased her. They called her "The woman doctor's child" because it was unusual for a woman to be a doctor back then. After finishing school, she briefly studied at the Woman's Medical College but decided not to become a doctor.

Career and Public Service

When Lucretia was young, a 22-year-old German man named Rudolph Blankenburg came to Philadelphia. He soon became a welcome visitor to her family's home. On April 18, 1867, Rudolph and Lucretia were married. They had three daughters, but sadly, none of them lived past childhood. After this difficult time, the Blankenburgs adopted a daughter.

Working for Change

After the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876, the Blankenburgs began their public work. They saw many ways to help their city. Lucretia joined a woman's club, which was quite new at the time. Many women's clubs focused on literature or music. However, Lucretia's club, the New Century Club, also started night classes for working women. Lucretia taught bookkeeping and helped plan cooking classes. She also helped create the New Century Guild, an organization for working women.

In 1892, Lucretia was elected President of the Pennsylvania Woman Suffrage Association. She held this important position until 1908, leading the fight for women's voting rights in Pennsylvania.

Lucretia worked hard to improve conditions for women. She helped get women like Anna Hallowell and Mary Mumford elected to the Board of Education in Philadelphia. Their work greatly benefited the city's schools. In 1895, her suffrage association helped pass a law. This law gave married mothers who supported their children equal rights to care for them. Before this, fathers usually had more rights unless they were proven unfit. She also worked for years to protect childless widows. She wanted them to have the same inheritance rights as childless widowers.

Lucretia was part of a group of women who started the system of police matrons in Philadelphia. These matrons were women who helped other women in police stations. The committee helped equip the first matron's department. Their efforts led to the appointment of four police matrons as an experiment. The matrons, with the committee's help, found clothing, homes, and jobs for women in need. This made the police matron system a permanent part of the police force. As a member of the Woman's Health Protective Association, Lucretia also helped improve public health. She supported efforts to get trolley fenders (safety devices), enclosed trolley cars, and better water filtration.

In 1903, Lucretia started a campaign against smoke pollution in Philadelphia. Even though there were laws, the city was still smoky. She organized a committee to convince businesses to reduce their smoke. In her own neighborhood, she gathered hundreds of signatures on a petition. This led some companies to change their fuel or reduce smoke. She also raised money to continue the fight for better anti-smoke laws in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, the state capital.

In 1904, Lucretia was a delegate from Philadelphia to the Second Conference of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance in Berlin. There, she spoke about the legal rights of women in the United States. She was also a member of the Good Citizens' Club and the Woman's City Party. She worked hard to inform people in her district about city government. She wrote simple "Civic Bulletins" with titles like "Do You Know the Tenth Ward?" and "City Housekeeping." These bulletins explained how the city government worked and important facts about their neighborhood.

Later Years and Influence

In 1911, Rudolph Blankenburg was elected mayor of Philadelphia. He was known as a leader in reform movements. Together, the Blankenburgs worked to improve society, make politics fairer, and encourage good citizenship. Their lives became even busier. Lucretia became a vice-president of the National Education Association and the General Federation of Women's Clubs. She received many letters asking for help, from finding jobs to even choosing wives!

Lucretia strongly believed in women's clubs and their motto, "Unity in Diversity." She supported clubs in Philadelphia and Pennsylvania, and the General Federation of Women's Clubs. She held many club offices and was a respected speaker at events. She was a member of the Society of Friends (Quakers). In 1914, she joined a movement to allow married women to keep their maiden names instead of always using their husband's name. She explained that Quaker women always used their own names after marriage. She used "Lucretia Longshore Blankenburg" for business but might use "Mrs. Rudolph Blankenburg" for social invitations.

Personal Life

Even with all her public service, the Blankenburgs' finances grew. Their home was comfortable and simple, showing their Quaker values. Lucretia managed her household, planned and cooked meals, and even made her own dresses.

Lucretia and Rudolph married on April 18, 1867, in a Quaker ceremony. They lived with Lucretia's parents for a time. In 1894, they bought a house at 214 West Logan Square. In 1916, they had to move because their block was being demolished for the expansion of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. Rudolph passed away on April 12, 1918, at their home in the Germantown neighborhood.

Lucretia Blankenburg passed away on March 28, 1937, in her apartment in Philadelphia, after being ill with pneumonia. She was buried in the city's Fair Hill Burial Ground.

Selected Works

- Pennsylvania law concerning women, 189?

- The Blankenburgs of Philadelphia, 1928 (a book about her husband and her own life story)