Manuel Álvarez Bravo facts for kids

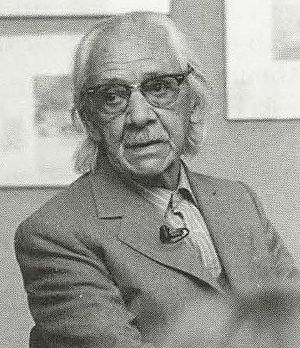

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (born February 4, 1902 – died October 19, 2002) was a famous Mexican photographer. He is known as one of the most important people in photography from Latin America in the 20th century. He was born and grew up in Mexico City.

Even though he took some art classes, he taught himself photography. His career lasted from the late 1920s to the 1990s. His best work was done between the 1920s and 1950s. Manuel Álvarez Bravo was special because he took pictures of everyday things but made them look surprising or dream-like.

At first, his work was like European art. But soon, he was inspired by the Mexican muralism movement. This was a time when Mexico wanted to show its own unique identity. He didn't want his photos to be like postcards or stereotypes. He used special ways to avoid that. He had many art shows, worked in Mexican movies, and even started a publishing company. He won many awards, especially after 1970. In 2017, his work was added to the UNESCO Memory of the World list.

Contents

Early Life and Photography Journey

Manuel Álvarez Bravo was born in Mexico City on February 4, 1902. His father was a teacher who also painted and made music. His grandfather was a professional portrait artist. This meant Manuel was around art from a young age.

He grew up in an old building in the center of Mexico City. It was near the Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral. When he was eight, the Mexican Revolution started. This big event later influenced his photos.

From 1908 to 1914, Manuel went to a boarding school. But he had to leave school at age twelve because his father died. He worked as a clerk in a factory and later for the government. He studied accounting at night for a while. Then he switched to art classes at the Academy of San Carlos.

In 1923, Álvarez Bravo met a photographer named Hugo Brehme. He bought his first camera in 1924. He started trying out photography, getting tips from Brehme and reading photography magazines. In 1927, he met another photographer, Tina Modotti. He already admired her work. Tina Modotti introduced him to many artists and thinkers in Mexico City. One of them was Edward Weston, who told him to keep taking photos.

Manuel Álvarez Bravo married three times. All three of his wives were also photographers. His first wife was Lola Alvarez Bravo. They married in 1925. He taught her photography. They had one son, Manuel, and separated in 1934. His second wife was Doris Heyden, and his third was Colette Álvarez Urbajtel.

In 1973, he gave his own collection of photos and cameras to the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes. The Mexican government also bought 400 more of his photos for the Museo de Arte Moderno. He passed away on October 19, 2002.

His Amazing Photography Career

Manuel Álvarez Bravo's photography career lasted from the late 1920s to the 1990s. His most important work happened after the Mexican Revolution. This was a time when Mexico was full of new ideas in art. The government even helped artists create new Mexican identity.

He started as a full-time photographer in 1930. That same year, Tina Modotti had to leave Mexico. She left Álvarez Bravo her camera and her job at Mexican Folkways magazine. For this magazine, he started taking pictures of the work of Mexican mural painters.

During the 1930s, he became a well-known photographer. In 1933, he met photographer Paul Strand while working on a film. In 1938, he met André Breton, a French artist who loved his work. Breton helped show Álvarez Bravo's photos in France. He even asked for a photo for a catalog cover. Álvarez Bravo created a famous photo called “La buena fama durmiendo” (The good reputation sleeping).

Álvarez Bravo taught many future photographers. These included Nacho López and Graciela Iturbide. He taught photography at art schools in the 1930s and 1960s.

From 1943 to 1959, he worked in the Mexican film industry. He took still photos for movies. He even experimented with making films himself. In 1957, he worked on the film Nazarín by Luis Buñuel.

He had over 150 solo art shows and was part of more than 200 group shows. His first solo show was in Mexico City in 1932. In 1935, he showed his work with Henri Cartier-Bresson. In 1955, three of his photos were chosen for a huge exhibition called The Family of Man at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. This show traveled the world and was seen by many people.

He also published books. In 1959, he helped start a publishing company called Fondo Editorial de la Plástica Mexicana. This company makes books about Mexican art. He spent most of the 1960s on this project.

Álvarez Bravo won many awards for his photography. One of his first big awards was in 1931 for a photo called La Tolteca. The famous painter Diego Rivera was one of the judges. Most of his other awards came after 1970. These include the Elias Sourasky Arts Prize, the Premio Nacional de Arte, and the Hasselblad Award. He also received the Master of Photography Prize in New York.

He kept taking photos until he passed away.

Important collections of his work are in Mexico and the United States. The Centro Fotográfico Álvarez Bravo in Oaxaca is a special place founded in 1996. It has six rooms for showing photos and a library about photography. It also has a permanent collection of 4,000 photos by Álvarez Bravo and others. Another big collection is at the Casa Lamm Cultural Center in Mexico City. Outside Mexico, the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles and the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena have many of his photos.

In 2005, Manuel Álvarez Bravo was added to the International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum.

What Made His Photos Special?

Manuel Álvarez Bravo was a pioneer in artistic photography in Mexico. He was the most important photographer in Latin America during the 20th century. His best creative work was from the 1920s to the 1940s. He knew that photography had challenges, like not being able to truly capture the past. He also worked hard to avoid making photos that were stereotypes.

He often photographed everyday people, folk art, and special ceremonies. He also took pictures of shop windows, city streets, and how people interacted. Even though he worked mostly in Mexico City, Diego Rivera told him to visit towns and rural areas too. His photos rarely showed powerful politicians. Instead, he preferred subjects from daily life. Most of the people in his photos are not named. He also liked to photograph different textures, like walls and floors.

He used large cameras that captured a lot of detail. But he cared more about the feeling of his photos than the perfect technical quality. His photos were usually very well put together and had a poetic feel. He gave titles to his photos to make them unique. These titles often came from Mexican myths and culture.

At first, Álvarez Bravo's work was influenced by European art styles like Cubism and French Surrealism. But after the Mexican Revolution, he started to focus on Mexican themes and styles. He was inspired by the Mexican mural movement. His photos became more complex. They included old symbols of blood, death, and religion. They also showed the confusing parts of Mexican culture. His experiences with death as a child during the Mexican Revolution influenced photos like “Striking Worker, Assassinated.” However, even though he was interested in Mexican identity, he wasn't very political.

Álvarez Bravo's special talent was finding hidden, dream-like meanings in ordinary images. He was the first Mexican photographer to actively avoid making "picturesque" photos. He didn't want to stereotype Mexico's many cultures. To do this, he took photos that went against what people expected to see about Mexico.

One way he did this was by using irony. He would add something unexpected to a photo. For example, in a photo of an indigenous man (Señor de Papantla 1934), the man looks back at the camera in a strong way. Another way was to show people doing normal things without making them seem overly romantic or emotional. For example, a photo of a mother and a shoeshine boy eating lunch together.

He used the streets and squares of Mexico City to show the social and cultural realities of the city. He showed Mexico City not as heroic, but as a place of social relationships and different groups of people. In the 1930s and 1940s, he found more and more complex ways to show the different sides of city life in Mexico.

See also

In Spanish: Manuel Álvarez Bravo para niños

In Spanish: Manuel Álvarez Bravo para niños

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |