Henri Cartier-Bresson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Henri Cartier-Bresson

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 22 August 1908 Chanteloup-en-Brie, France

|

| Died | 3 August 2004 (aged 95) Céreste, France

|

| Burial place | Montjustin, France |

| Alma mater | Lycée Condorcet, Paris |

| Occupation | Photographer and painter |

| Spouse(s) |

Ratna Mohini

(m. 1937; div. 1967) |

| Children | 1 |

| Awards | Grand Prix National de la Photographie in 1981 Hasselblad Award in 1982 |

Henri Cartier-Bresson (born August 22, 1908 – died August 3, 2004) was a famous French photographer. He was known for taking natural, unplanned photos of people and everyday life. He was one of the first to use small 35mm cameras. He also helped create a type of photography called "street photography." Cartier-Bresson believed that photography was all about capturing the "decisive moment." This meant finding the perfect moment to take a picture.

He was one of the people who started Magnum Photos in 1947. Later in his life, in the 1970s, he went back to drawing. He had studied painting when he was younger.

Contents

Early Life and Art Studies

Henri Cartier-Bresson was born in Chanteloup-en-Brie, France. His father owned a successful company that made textiles. His mother's family were cotton merchants from Normandy. Henri spent some of his childhood there. His family was quite wealthy and lived in a nice part of Paris. Because his parents supported him financially, Henri could explore photography more freely.

When he was young, Henri took holiday pictures with a simple camera called a Box Brownie. He also tried using a larger camera. His parents raised him in a traditional French way. He had to use formal language when speaking to them. His father hoped Henri would take over the family business. But Henri was strong-willed and didn't want to do that.

Henri went to a Catholic school and then to Lycée Condorcet. A governess from England taught him to love and speak English well. One time, his teacher caught him reading a book by a poet. The teacher told him, "Let's have no disorder in your studies!" Henri said the teacher then invited him to read in his office.

Learning to Paint

Henri first tried to learn music. Then, his uncle Louis, who was a talented painter, introduced him to oil painting. Sadly, his painting lessons stopped when his uncle died in World War I.

In 1927, Cartier-Bresson went to a private art school. He also studied at the Lhote Academy in Paris. This was the studio of André Lhote, a Cubist painter. Lhote wanted to mix the Cubist way of looking at things with older, classical art styles. Cartier-Bresson also learned painting from Jacques Émile Blanche, a portrait artist.

During this time, he read many books by famous writers and thinkers. His teacher, Lhote, took his students to the Louvre museum to study old masters. He also took them to galleries to see modern art. Cartier-Bresson loved modern art but also admired artists from the Renaissance. He saw Lhote as his teacher for "photography without a camera."

Inspired by Surrealism

Cartier-Bresson felt frustrated with Lhote's strict rules for art. But this training later helped him understand how to create good art and photos. In the 1920s, new ideas about photography were appearing in Europe. The Surrealist movement, which started in 1924, was a big influence. Cartier-Bresson started spending time with Surrealist artists in Paris. He met many of the movement's leaders. He was drawn to their idea of using the subconscious mind and immediate feelings in their art.

Cartier-Bresson grew as an artist during this exciting time. He had many ideas but struggled to express them. He wasn't happy with his early paintings and destroyed most of them.

Army and First Camera

From 1928 to 1929, Cartier-Bresson studied art, literature, and English at the University of Cambridge. He became fluent in English. In 1930, he joined the French Army. He was stationed near Paris. He later joked about carrying both a book by James Joyce and his army rifle.

In 1929, Cartier-Bresson was put under house arrest by his air squadron leader. He had been hunting without a license. He met an American named Harry Crosby, who convinced the leader to release Cartier-Bresson into his care. Both men loved photography. Harry gave Henri his first camera. They spent time taking and printing pictures at Crosby's home near Paris. Crosby later described Cartier-Bresson as "shy and frail."

Adventure in Africa

While in the army, Cartier-Bresson read a book called Heart of Darkness. This made him want to escape and find adventure in Africa. He went to the Ivory Coast. He survived by hunting animals and selling them to local villagers. From hunting, he learned skills he later used in photography. In Africa, he got very sick with a fever that almost killed him. He took a small camera with him, but only seven of his photos survived the tropical climate.

Photography and the Decisive Moment

When he returned to France, Cartier-Bresson recovered in Marseille in late 1931. He spent more time with the Surrealists. He was greatly inspired by a 1930 photo by Martin Munkacsi. It showed three young African boys running into the ocean. This photo, called Three Boys at Lake Tanganyika, captured their freedom and joy. It made him decide to stop painting and focus seriously on photography. He said, "I suddenly understood that a photograph could fix eternity in an instant."

He bought a Leica camera with a 50mm lens in Marseille. This camera stayed with him for many years. The small camera allowed him to be unnoticed in a crowd. This was important for taking natural pictures of people. He even painted the shiny parts of his Leica black to make it less visible. The Leica opened up new ways to take photos. It allowed him to capture the world as it moved and changed. He traveled and photographed in many cities like Berlin, Brussels, and Madrid. His first photos were shown in New York in 1933. Later, he had an exhibition in Mexico with Manuel Álvarez Bravo. At first, he didn't take many photos in his home country, France.

In 1934, Cartier-Bresson met two other photographers who became his friends: David Szymin (known as "Chim") and Robert Capa.

Exhibitions in the United States

Cartier-Bresson went to the United States in 1935 to show his work in New York. He shared the exhibition space with Walker Evans and Manuel Álvarez Bravo. A magazine editor gave him a job to photograph fashion. But he wasn't good at it because he didn't know how to direct models. Still, she was the first American editor to publish his photos in a magazine. In New York, he met photographer Paul Strand.

Making Films

When he returned to France, Cartier-Bresson worked with the famous French film director Jean Renoir. He acted in Renoir's films in 1936 and 1939. He even played a butler in one film. Renoir made him act so he could understand what it felt like to be in front of the camera. Cartier-Bresson also helped Renoir make a film about the wealthy families who ran France. During the Spanish Civil War, Cartier-Bresson helped direct a film against fascism. It promoted medical services for the Republican side.

Starting Photojournalism

Cartier-Bresson's first photojournalism pictures were published in 1937. He covered the coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth for a French magazine. He focused on the people lining the streets, not the king himself. His photos were credited as "Cartier" because he didn't want to use his full family name.

Marriage and World War II

In 1937, Cartier-Bresson married Ratna "Elie" Mohini, a dancer. They lived in a small apartment in Paris. Between 1937 and 1939, Cartier-Bresson worked as a photographer for a French newspaper. He was a leftist, like his friends Chim and Capa, but he didn't join the Communist party. He and Ratna divorced in 1967.

In 1970, Cartier-Bresson married Martine Franck, who was also a photographer. In 1972, they had a daughter named Mélanie.

Serving in World War II

When World War II started in 1939, Cartier-Bresson joined the French Army. He was a corporal in the film and photo unit. In June 1940, he was captured by German soldiers. He spent 35 months in prisoner-of-war camps, doing forced labor for the Nazis. He tried to escape twice but failed and was punished. His third escape was successful. He hid on a farm and got false papers to travel in France. He then worked secretly with the French underground. He helped other escapees and photographed the German Occupation and the Liberation of France. In 1943, he dug up his beloved Leica camera, which he had buried. After the war, he made a documentary film called Le Retour (The Return) about French prisoners returning home.

Towards the end of the war, people in America thought Cartier-Bresson had died. But his film about war refugees showed he was alive. This led to a special exhibition of his work at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York in 1947. His first book, The Photographs of Henri Cartier-Bresson, was also published that year.

Magnum Photos and Global Work

In early 1947, Cartier-Bresson, along with Robert Capa, David Seymour, William Vandivert, and George Rodger, started Magnum Photos. Magnum was a cooperative agency owned by its photographers. The team divided assignments among themselves. Rodger covered Africa and the Middle East. Chim worked in Europe. Cartier-Bresson was assigned to India and China. Vandivert worked in America, and Capa worked wherever there was a story.

Cartier-Bresson became famous for his photos of Gandhi's funeral in India in 1948. He also covered the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949. He photographed the last six months of the old Chinese government and the first six months of the new communist government. He even photographed the last surviving Imperial eunuchs in Beijing. From China, he went to Indonesia, where he documented their fight for independence. In 1950, he traveled to South India and photographed Ramana Maharishi and Sri Aurobindo.

Magnum's goal was to "feel the pulse" of the times. They wanted to use photography to help humanity. They provided powerful images that were seen by many people.

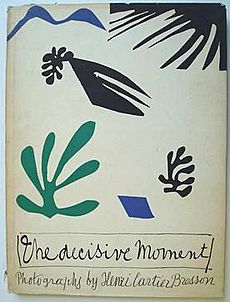

The Decisive Moment

In 1952, Cartier-Bresson published his famous book, Images à la sauvette. The English version was called The Decisive Moment. The French title actually means "images on the sly" or "hastily taken images." The book included 126 of his photos from different parts of the world. The cover was drawn by the artist Henri Matisse. For the book's introduction, Cartier-Bresson used a quote from the 17th century: "There is nothing in this world that does not have a decisive moment." He applied this idea to his photography. He said that photography is about recognizing an event and finding the perfect way to show it visually, all in a fraction of a second.

He explained to The Washington Post in 1957: "There is a creative fraction of a second when you are taking a picture. Your eye must see a composition or an expression that life itself offers you, and you must know with intuition when to click the camera. That is the moment the photographer is creative. Oop! The Moment! Once you miss it, it is gone forever."

His photo Rue Mouffetard, Paris, taken in 1954, is a great example of his ability to capture this decisive moment. He had his first exhibition in France in 1955.

Later Career and Legacy

Cartier-Bresson's photography took him to many countries, including China, Mexico, the United States, India, Japan, and the Soviet Union. He was the first Western photographer allowed to photograph freely in the Soviet Union after the war.

In 1966, he stepped back from being a main part of Magnum. He wanted to focus more on taking portraits and landscape photos.

In 1968, he started to move away from photography and return to his love for drawing and painting. He felt he had said all he could through photography. He married photographer Martine Franck in 1970.

Cartier-Bresson mostly stopped taking pictures in the early 1970s. By 1975, he rarely took photos, except for an occasional private portrait. He said he kept his camera in a safe. He went back to drawing and painting. He had his first exhibition of drawings in New York in 1975.

Death and Impact

Cartier-Bresson died on August 3, 2004, at the age of 95. He was buried in Montjustin, France. His wife, Martine Franck, and daughter, Mélanie, survived him.

Cartier-Bresson spent over 30 years working for magazines like Life. He traveled widely and documented many big events of the 20th century. These included the Spanish Civil War, the liberation of Paris in 1944, the fall of the old Chinese government, the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi, and events in Paris in 1968. He also took portraits of famous people like Camus, Picasso, and Matisse. But many of his most famous photos are of simple, everyday moments.

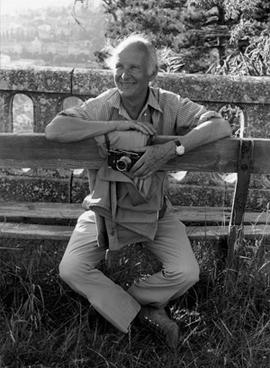

Cartier-Bresson didn't like to be photographed and valued his privacy. There are very few photos of him. When he received an honorary degree from Oxford University in 1975, he held a paper in front of his face to avoid being photographed. In an interview in 2000, he said he wasn't that he hated being photographed, but that he was embarrassed by being photographed just for being famous.

In 2003, he created the Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation in Paris with his wife and daughter. Its purpose is to protect and share his work.

Photography Style

Cartier-Bresson almost always used a Leica 35mm camera. It usually had a normal 50mm lens. Sometimes he used a wide-angle lens for landscapes. He often put black tape around his camera to make it less noticeable. Using fast black and white film and sharp lenses, he could photograph events without being seen. He called his small camera "the velvet hand...the hawk's eye."

He never used a flash. He thought it was "impolite...like coming to a concert with a pistol in your hand."

He believed in composing his photos perfectly through the camera's viewfinder. He didn't like to crop or change his photos in the darkroom. He insisted that his prints be left uncropped. This meant they often had a thin black border from the edge of the film.

Cartier-Bresson worked only in black and white, except for a few color experiments. He didn't like developing his own film or making prints. He wasn't very interested in the technical side of photography. He compared taking photos with a small camera to "instant drawing."

He had a unique tradition: he would test new camera lenses by taking pictures of ducks in city parks. He never published these images. He called it his "only superstition" and saw it as a "baptism" for the lens.

Cartier-Bresson was known for being very humble. He disliked publicity and was very shy. Even though he took many famous portraits, his own face was not well known. This probably helped him work on the street without being disturbed. He didn't think his photographs were "art." He felt they were just his quick reactions to moments he came across.

Films Directed by Cartier-Bresson

Cartier-Bresson also worked as an assistant director for Jean Renoir on several films.

- 1937: Victoire de la vie (Documentary about hospitals in Republican Spain)

- 1938: L’Espagne Vivra (Documentary about the Spanish Civil War)

- 1944–45: Le Retour (Documentary about returning prisoners of war)

- 1969–70: Impressions of California (Color film)

- 1969–70: Southern Exposures (Color film)

Films About Cartier-Bresson

- "Henri Cartier-Bresson, point d'interrogation" by Sarah Moon (1994)

- Henri Cartier-Bresson: L'amour Tout Court (2001, interviews with Cartier-Bresson)

- Henri Cartier-Bresson: The Impassioned Eye (2006, later interviews with Cartier-Bresson)

Exhibitions

Henri Cartier-Bresson's work has been shown in many exhibitions around the world. Here are some of the notable ones:

- 1933: Julien Levy Gallery, New York

- 1947: Museum of Modern Art, New York

- 1955: Retrospective – Musée des Arts décoratifs, Paris

- 1965–1967: 2nd retrospective, Tokyo, Paris, New York, London, and other cities.

- 1970: En France – Grand Palais, Paris. Later in the US, USSR, Australia, and Japan.

- 1980: Brooklyn Museum, New York

- 1997: Les Européens – Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris

- 2003–2005: Retrospective, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris; and other major museums worldwide.

- 2014: Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris.

Public Collections

Cartier-Bresson's photographs are kept in many important public collections, including:

- Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, France

- Foundation Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paris, France

- Victoria and Albert Museum, London, United Kingdom

- Museum of Modern Art, New York City

- The Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois, US

- J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

- International Photography Hall of Fame, St. Louis, Missouri

Awards

Cartier-Bresson received many awards for his photography:

- 1948: Overseas Press Club of America Award

- 1953: The A.S.M.P. Award

- 1964: Honorary Fellowship of the Royal Photographic Society

- 1981: Grand Prix National de la Photographie

- 1982: Hasselblad Award

- 2003: Lifetime Achievement Award from the Lucie Awards

- 2006: Prix Nadar for his photobook Henri Cartier-Bresson: Scrapbook

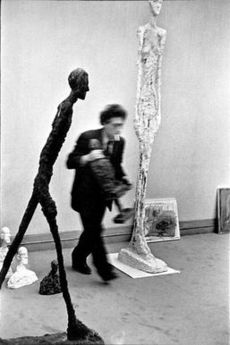

Images for kids

-

Photograph of Alberto Giacometti by Cartier-Bresson

See also

In Spanish: Henri Cartier-Bresson para niños

In Spanish: Henri Cartier-Bresson para niños

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |