Maria Perkins letter facts for kids

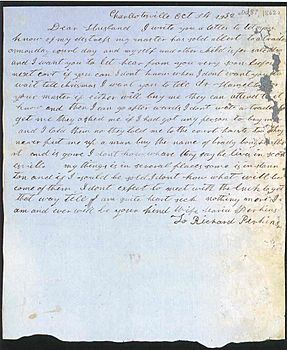

On October 8, 1852, Maria Perkins, an enslaved woman in Charlottesville, Virginia, United States, addressed a letter to her husband, also enslaved. In the letter, she writes that their son Albert has been sold to a trader, that she fears that she too might be sold, and that she wants their family reunited. Perkins was literate, uncommon among slaves, and all that is known about her comes from the sole letter.

Ulrich Bonnell Phillips discovered the letter and published it in 1929. Christopher Hager, in his book Word by Word (2013), critically analyzes the document as a case study, suggesting that throughout the letter her writing moves from correspondence to frantic diary. Often cited as an example of slave writing, Perkins's letter is quoted by textbooks to illustrate slaves' personal struggle, heartbreak, and strategic thinking.

Background

The literacy rate among 19th-century slaves is estimated to have ranged from 5 to 20 percent. Though a substantial number of letters written by slaves have survived, accounts of African-American life in the antebellum period were more commonly studied through slave narratives, written or dictated by former slaves. Few slaves were "free" enough to write to family members to warn that they might soon be taken away. "It is seldom that the historian finds recorded the personal emotion of the victims of the internal slave trade," author Willie Lee Nichols Rose writes about Maria Perkins's letter. Historian Christopher Hager calls the genre of works by people at the time of enslavement the "enslaved narrative".

Perkins's letter was discovered by Yale University historian Ulrich Bonnell Phillips, who published it in Life and Labor of the American South (originally 1929). Phillips most likely found the letter among thousands of documents in a farmhouse outside Greenville, Augusta County, Virginia. Phillips and his friend Herbert Kellar visited the house and bought the collection of about 25,000 documents from farmer George Armentrout. Prefacing Perkins's writing in Life and Labor, Phillips reflects on "a letter which lies before me in the slave's own writing," one of the few slave letters published in the book. He adds: "We cannot brush away this woman's tears."

Maria Perkins

Maria Perkins was a slave from Charlottesville, Virginia. The letter she wrote which begins, "My master has sold Albert to a trader," is the only document that survives about her life. In the letter, she writes that Albert, her son, had been taken away by a trader named Brady, perhaps to Scottsville or further. Maria thought that she herself would soon be sold, as well. The letter, dated October 8, 1852, was written from Charlottesville to her husband Richard, who was owned by a different master. She told him that Albert had been sold and, fearing further estrangement, that she wanted to try to reunite their family suggesting possible actions—but rarely could slaves have such control over their future. She asked her husband to try to convince his owner or a Dr. Hamilton to buy her and an "other child".

According to historian David Brion Davis, Perkins was almost certainly one of the more than one million slaves who were in the 1850s taken from their original residences by traders to the Old Southwest. Perkins "was naturally more alarmed at the prospect of being bought by a trader who might sell her far from home and family," Willie Lee Nichols Rose writes, "than if he were a local person." The Perkins family's situation was out of their control, author Walter Dean Myers wrote in 1992: "It is the dignity of the human reduced to the idea of thing. For this is what this woman has become. This is what her child has become. It is a situation that no kind treatment can assuage, a wound of the soul that will never heal."