Mary Agnes Chase facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Mary Agnes Chase

|

|

|---|---|

Mary Agnes Chase seated at a desk with herbarium sheets, c.1960

|

|

| Born | April 29, 1869 Iroquois County, Illinois

|

| Died | September 24, 1963 (aged 94) |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | Agnes Chase |

| Known for | First Book of Grasses |

| Spouse(s) | William Ingraham Chase |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | botany, botanical illustration |

| Institutions | U.S. Department of Agriculture, Smithsonian Institution |

| Author abbrev. (botany) | Chase |

Mary Agnes Chase (1869–1963) was an amazing American botanist. She was an expert in agrostology, which is the study of grasses. Even though she only finished elementary school, Mary Agnes became a top scientist.

She started as an illustrator at the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Her mentor, Albert Spear Hitchcock, helped her learn a lot. Eventually, she became a senior botanist. She even led the USDA's grass study department!

Mary Agnes traveled to Europe and South America for her research. She wrote several important books. One famous book was First Book of Grasses: The Structure of Grasses Explained for Beginners. It was even translated into Spanish and Portuguese.

She received many awards for her work with grasses. In 1956, the Botanical Society of America gave her a special Certificate of Merit. Mary Agnes was also a strong supporter of women's rights. She joined the Silent Sentinels, a group from the National Woman's Party. They worked hard to get women the right to vote. Even when some scientists didn't like her political actions, she never stopped fighting for women's suffrage.

Contents

Early Life and Career Beginnings

Mary Agnes Meara was born in 1869 in rural Iroquois County, Illinois. Her family later moved to Chicago after a difficult family event. They also changed their last name to Merrill. Mary Agnes was the third of six children. Her mother and grandmother raised her in Chicago. She went to school but finished her formal education after elementary school.

In 1888, she married William Ingraham Chase. Sadly, her husband passed away just one year later.

Mary Agnes worked as a proofreader for a newspaper. She also took botany classes at the University of Chicago. Soon, E.J. Hill hired her to draw pictures for his books. Her drawings became well-known. Charles Frederick Millspaugh then hired her to illustrate for the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago.

In 1903, Mary Agnes started working at the U.S. Department of Agriculture in Washington, D.C. She began as an illustrator in the Division of Agrostology. She worked closely with Albert Spear Hitchcock. He quickly saw her talent. He started treating her as a partner, not just a student.

In 1910 and 1915, Chase and Hitchcock wrote two books together. These books were about North American grass species called Panicum. In 1917, they published Grasses of the West Indies. This book used a lot of information from Mary Agnes's fieldwork in Puerto Rico.

In 1911, Hitchcock went on a trip to the Panama Canal zone. The Smithsonian Institution paid for his trip. When he came back, he asked for some money to help Mary Agnes with her own fieldwork. But a Smithsonian official said no. They said they weren't sure about "engaging the services of a woman" for such a trip.

Fighting for Women's Rights

Mary Agnes Chase believed it was important to fight unfair treatment against women. She knew that her support for women's rights might hurt her career. But she still chose to speak up. She wanted to help women succeed in all parts of life.

Mary Agnes was an active suffragist. She joined the Silent Sentinels in their protests. These women were part of the National Woman's Party (NWP). They wanted President Wilson to listen to women's demands for the right to vote.

The "Silent Sentinels" tried many ways to get their message across. They sent 300 women to meet the President. They wanted to discuss a federal amendment for women's suffrage. Women even held a "Votes for Women" banner inside the White House gallery. They picketed outside the White House gates every day. Their signs asked, "What Will You Do for Woman Suffrage?" and "Mr. President, How Long Will Women Have to Wait for Liberty?".

Each day of the protest had a special theme. This allowed women from all backgrounds to be part of the movement. There were "State Days" for women to represent their states. There were also "Professional Days" for women to represent their jobs, like science or journalism.

The "Silent Sentinels" planned to protest until a solution was found. Other women's suffrage groups thought their actions were too strong. But many people who supported the movement donated money. They raised over $3000 to keep the protests going. Mary Agnes herself promised to burn any of President Wilson's writings that used words like "liberty" or "freedom" until women could vote.

Because of these protests, many NWP women were arrested. They were sent to workhouses. When the public learned that some of these women had gone on a hunger strike, support for the suffrage cause grew even more. This public sympathy helped get Mary Agnes and others released from the workhouses. The strong efforts of the NWP played a big part. They helped lead to the Suffrage Amendment in 1919 and the 19th Amendment in 1920. This amendment finally gave women the right to vote.

Global Research and Later Career

In 1922, Mary Agnes published her First Book of Grasses. This book was for serious students who were just starting to learn about grasses. It was not for professional botanists.

That same year, she traveled across western Europe. She visited different plant collections, called herbaria. She went to the Hackel Herbarium in Vienna. There, she worked with Eduard Hackel to collect mountain grass samples.

In 1923, she became an assistant botanist at the USDA. In 1925, she was promoted again to associate botanist.

In 1924, Mary Agnes did fieldwork in Brazil. Several groups, including the USDA and the Field Museum, helped pay for this trip. She collected about 20,000 plant species in Brazil. About 500 of these were grasses. When she returned to Brazil in 1929, she found ten new types of grasses.

In Brazil, she worked with local botanists like Doña María do Carmo Bandeira. This helped her connect with more female scientists. Before her trips to Latin America, Mary Agnes contacted American female missionaries there. They hosted her and helped her with her international fieldwork. This support was very important, as American science groups didn't always help women with their travels.

Mary Agnes often paid for her own fieldwork. But the plants she found and collected became the property of the National Herbarium. Her trips to Brazil and the thousands of plants she brought back earned her a special nickname: "Uncle Sam's chief woman explorer of the USDA."

In 1935, Chase and Hitchcock published another book. It was called Manual of the Grasses of the United States. This book was very popular. It was reprinted eight times by 1938.

In 1936, she became a senior botanist. She was put in charge of the USDA's entire department for studying grasses. Three years later, in 1939, Mary Agnes retired from the USDA after 36 years of work.

Even after retiring, she continued her work. She stayed as the custodian of grasses at the U.S. National Herbarium. She held this job until she passed away in 1963. She was known as the "foremost grass specialist in the world."

Starting in 1941, Mary Agnes became a mentor to George Black. He was an American botanist working in Brazil. Black would collect plant samples for Chase. She would then send him plant identifications, samples, books, and advice.

Mary Agnes also helped other women in science. She traveled to South America, Canada, and the Philippines. She was a kind and supportive mentor. She encouraged her students to be independent. She even opened her home to young women who needed a place to stay while studying in the United States. One of these women was Zoraida Luces, whom Chase met in Brazil. Luces came to Washington D.C. and studied with Chase. Later, Luces translated Chase's First Book of Grasses into Spanish.

Mary Agnes Chase received many awards and honors. In 1956, she got a Certificate of Merit from the Botanical Society of America. In 1958, she received her only college degree. It was an honorary Doctor of Science from the University of Illinois. She also became the eighth Honorary Fellow of the Smithsonian Institution. In 1961, two years before she died, she became a Fellow at the Linnean Society of London.

Botanical Collections

Mary Agnes Chase's plant collections are kept in many herbaria around the world. These include:

- The United States National Herbarium

- The National Herbarium of Victoria in Australia

- The University of Michigan Herbarium

- The Gray Herbarium at Harvard University Herbaria

- The Swedish Museum of Natural History

- The herbarium at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew in England

Awards and Honors

- 1956: Certificate of Merit from the Botanical Society of America

- 1958: Honorary doctorate from the University of Illinois

- 1958: Honorary fellowship of the Smithsonian Institution

- 1961: Fellow from the Linnean Society of London

Publications

- 1915: Hitchcock, A. S. & A. Chase. Tropical North American species of Panicum.

- 1917: Hitchcock, A. S. & A. Chase. Grasses of the West Indies.

- 1922: Chase, A. First book of grasses: The structure of grasses explained for beginners.

- 1951: Chase, A. & A. S. Hitchcock. Manual of the grasses of the United States, Second Edition.

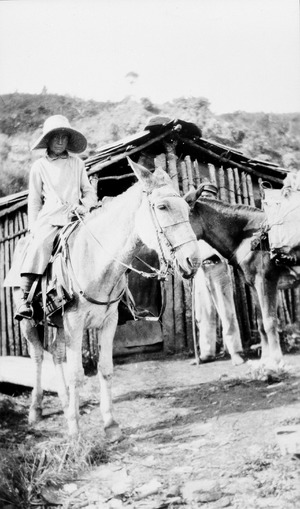

Images for kids

Error: no page names specified (help). In Spanish: Mary Agnes Chase para niños

In Spanish: Mary Agnes Chase para niños

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |