North Pacific hake facts for kids

Quick facts for kids North Pacific hake |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Synonyms | |

|

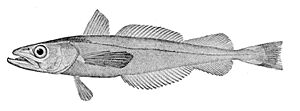

The North Pacific hake, also called Pacific hake or Pacific whiting, is a type of ray-finned fish. It lives in the northeastern Pacific Ocean, from northern Vancouver Island down to the northern part of the Gulf of California. This fish is silver-gray with black speckles and can grow up to about 90 cm (3 feet) long.

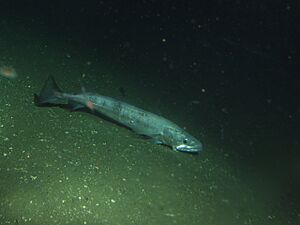

North Pacific hake are migratory fish that live far offshore. They move up and down in the water every day, from the surface down to about 1000 meters (3,280 feet) deep. This fish is very important for commercial fishing along the West Coast of the United States. To make sure there are enough fish for the future, limits are set on how many can be caught each year.

Contents

About the North Pacific Hake

The North Pacific hake can grow to be about 90 cm (3 feet) long. It can live for up to 20 years. Its body is a shiny silver-gray with black spots, and its belly is pure silvery white.

This fish has two fins on its back, called dorsal fins. Its tail fin is somewhat flat or slightly curved inward. The fins on its sides, called pectoral fins, usually reach past the start of its fin on the underside, called the anal fin.

Life Cycle and Reproduction

North Pacific hake lay their eggs from January to June. They might lay eggs more than once in a single season. This makes it tricky to count exactly how many eggs a female fish can produce.

In the past, female Pacific hake living closer to shore would become ready to reproduce when they were about 37 cm (15 inches) long and 4 to 5 years old. Today, female hake in the Port Susan area are ready to reproduce when they are much smaller, around 21.5 cm (8.5 inches). This is different from the 29.8 cm (11.7 inches) they needed to be in the 1980s.

Most females are ready to reproduce by age 3 or 4, when they are between 34 and 40 cm (13.4 to 15.7 inches) long. Almost all males are ready to reproduce by age 3, even if they are as small as 28 cm (11 inches).

Where They Live and What They Eat

North Pacific hake can be found from the ocean surface down to depths of about 1000 meters (3,280 feet). They are active at night, moving up from the bottom to feed on different fish and small sea creatures. Their diet includes shrimp, tiny floating organisms called plankton, and smaller fish like lanternfish.

These hake are also an important food source for other animals. Sea lions, small whales, and dogfish sharks often hunt and eat them.

There are three main groups, or "stocks," of Pacific hake. One group is highly migratory and travels along the coast from southern California to Queen Charlotte Sound. The other two groups live in specific areas: one in central-south Puget Sound and another in the Strait of Georgia.

The coastal group of North Pacific hake used to lay their eggs off south-central California and Baja California in January and February. In spring and summer, these adult fish would travel north to feed, sometimes as far as central Vancouver Island or even Queen Charlotte Sound. In the fall, they would swim back south to their spawning areas.

Since the early 1990s, some of the coastal hake have started staying off the west coast of Canada all year. Some have even been seen laying eggs off the west coast of Vancouver Island. The hake that live in Puget Sound lay their eggs in Port Susan and Dabob Bay from February to April. The group living in the Strait of Georgia gathers to lay eggs in the deep parts of the central strait, mostly from March to May.

Fishing and Protecting Hake

Pacific hake are very important for commercial fishing along the West Coast of the United States. The two smaller groups of hake (in Puget Sound and the Strait of Georgia) are managed by local and state agencies. However, the large coastal group in U.S. waters is managed by the Pacific Fishery Management Council. This council uses a plan that helps manage over 90 different fish species.

To control how many hake are caught, the main tool used is annual quotas. These are limits on the total amount of fish that can be caught. In 2002, the U.S. government said that Pacific hake were "overfished," meaning too many had been caught. But by 2004, the fish population had recovered and was declared "rebuilt." Scientists from both the U.S. and Canada check the coastal hake population every year.

In 2003, the U.S. and Canada signed an agreement. This agreement decided what percentage of the Pacific hake catch would go to American fishermen and what would go to Canadian fishermen for the next ten years. It also set up a way for scientists to review information and suggest ways to manage the fish. Since late 2007, the management of Pacific hake and related science has been guided by this international agreement with Canada.

Recent studies show that the coastal group of Pacific hake is at a healthy level. This means that too many fish are not being caught. Because of these studies, the Marine Stewardship Council certified the coastal Pacific hake fishery in the U.S. and Canada as sustainable in 2009. This certification was renewed in 2014, meaning the fishing practices are good for the environment and the fish population.

The hake groups in Puget Sound and the Strait of Georgia are considered "species of concern." This means that the NOAA Fisheries Service is worried about their population status and threats they face. However, there isn't enough information to list them under the Endangered Species Act (ESA), which protects species that are in danger of disappearing. No commercial fishing has been allowed for these specific groups since 1991.

The National Marine Fisheries Service once received a request to list the North Pacific hake under the ESA. This request was denied in 2000, but some worries remained. During the review, a specific group of hake called the Georgia Basin "distinct population segment" (DPS) was identified. This DPS includes both the Puget Sound and Strait of Georgia hake. This group was made a US National Marine Fisheries Service species of concern.

One concern for hake is the possible increase in Humboldt squid. These squid are predators, meaning they hunt and eat hake.