Minor White facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

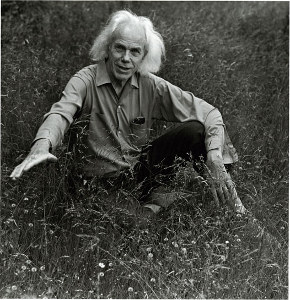

Minor White

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | July 9, 1908 Minneapolis, Minnesota

|

| Died | June 24, 1976 Boston, Massachusetts

|

| Nationality | American |

| Education | University of Minnesota |

| Known for | Photography |

Minor Martin White (born July 9, 1908 – died June 24, 1976) was an American photographer, writer, and teacher. He was very interested in how people looked at and thought about photos. His own way of seeing the world was shaped by different spiritual and intellectual ideas.

From 1937 until he died in 1976, White took thousands of black-and-white and color photographs. His pictures showed landscapes, people, and abstract shapes. They were known for his great skill and strong use of light and shadow. He taught many photography classes and workshops at places like the California School of Fine Arts and the Rochester Institute of Technology.

He also helped start the photography magazine Aperture. This magazine was special because it was made for and by photographers who saw photography as a fine art. Minor White was its editor for many years. After he passed away in 1976, many people called him one of America's greatest photographers.

Contents

Biography

Early Life and Discovering Photography: 1908–1937

Minor White was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He was the only child of Charles Henry White and Florence May Martin White. He spent a lot of time with his grandparents and loved playing in their big garden. This love for nature later made him study botany in college.

His grandfather, George Martin, was a hobby photographer. He gave Minor his first camera in 1915. Minor's parents had some difficult times when he was young. In 1927, after a personal challenge, he left home for a short time. He returned in the fall to study botany at the University of Minnesota.

By 1931, he took a break from school. During this time, he became very interested in writing. He started a personal journal called "Memorable Fancies." In it, he wrote poems, thoughts about his life, and later, many notes about his photography. He kept this journal until 1970.

In 1932, White went back to the university to study botany and writing. He graduated in 1934. He took some more botany classes but decided he didn't want to be a botanist. For the next two years, he worked odd jobs and practiced his writing.

Starting a Photography Career: 1937–1945

In late 1937, White decided to move to Seattle. He bought a small camera and took a bus. He stopped in Portland, Oregon, and decided to stay there. For the next two and a half years, he lived at the Portland YMCA. He learned a lot about photography during this time. He taught his first photography class to young adults at the YMCA. He also joined the Oregon Camera Club to learn from other photographers.

In 1938, White got a job as a photographer for the Oregon Art Project. This project was part of the Works Progress Administration, a government program that created jobs during the Great Depression. One of his jobs was to photograph old buildings in downtown Portland before they were torn down. He also took pictures for the Portland Civic Theater, showing their plays and actors.

In 1940, White was hired to teach photography at the La Grande Art Center in eastern Oregon. He taught classes, gave talks about art, wrote reviews for the local newspaper, and had a weekly radio show. In his free time, he traveled and photographed the landscapes, farms, and small towns. He also wrote his first article about photography, which was published in 1942.

White left the Art Center in late 1941 and returned to Portland. He planned to start his own photography business. That year, the Museum of Modern Art in New York bought three of his photographs for an exhibition. This was the first time his pictures were part of a public collection. The next year, the Portland Art Museum held his first solo show, featuring photos he took in eastern Oregon.

In April 1942, White joined the United States Army during World War II. He spent two years in Hawaii and Australia. Later, he worked in the southern Philippines. He didn't take many photos during this time. Instead, he wrote poetry about his war experiences.

After the war, White went to New York City and studied at Columbia University. There, he met Beaumont and Nancy Newhall, who worked at the Museum of Modern Art's new photography department. They offered him a job as a museum photographer. Nancy Newhall especially helped him develop his ideas about photography.

Developing His Style: 1946–1964

In 1946, White met the famous photographer Alfred Stieglitz in New York. White learned about Stieglitz's idea of "equivalence." This idea means that a photograph can show something deeper than just what is in the picture. For example, a photo of a tree bark might make someone feel a sense of strength. White also learned about showing photos in a series, or "sequence."

White also met other important photographers like Edward Steichen and Edward Weston. Steichen offered him a job at the Museum of Modern Art. But White chose to work with Ansel Adams at the California School of Fine Arts (CSFA) in San Francisco. Adams taught White his "Zone System," a way to control light and shadow in photos. White used this method a lot and taught it to his students.

In San Francisco, White became good friends with Edward Weston. Weston greatly influenced White's photography and ideas. White later said that Stieglitz, Weston, and Adams each taught him something important: technique from Adams, love of nature from Weston, and confidence from Stieglitz. White spent a lot of time photographing at Point Lobos, a place where Weston took many famous pictures. White photographed the same subjects but with his own unique view.

By 1947, White was the main teacher at CSFA. He created a three-year course focused on personal expression in photography. He invited other great photographers like Imogen Cunningham and Dorothea Lange to teach there. During this time, White created his first photo sequence with text, called Amputations.

The years 1951–1952 were very important for White's career. He attended a conference where the idea of a new photography magazine was discussed. Soon after, Aperture magazine was founded. White became its editor, and the first issue came out in April 1952. Aperture quickly became a very important magazine for photographers, and White remained editor until 1975.

In 1953, White learned about the I Ching, an ancient Chinese book of philosophy. He was especially interested in the ideas of yin and yang, which describe how opposite forces can actually be connected and complete each other. Later that year, he moved to Rochester, New York, to work at the George Eastman House museum. In 1955, he also started teaching at the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT).

White's own photography slowed down because of his teaching and editing work. But he still created new photos, including a sequence called Sequence 10/Rural Cathedrals. He also started taking his first color photos around 1955. His collection includes nearly 9,000 color slides taken over 20 years.

In 1959, White had a large exhibition of 115 photos at the George Eastman House. It was called Sequence 13/Return to the Bud. This show later traveled to the Portland Art Museum. White also developed the idea for a full-time photography workshop where students would learn through formal lessons and daily tasks. He continued this style of teaching for the rest of his life.

Later Career and Legacy: 1965–1976

In 1965, White was invited to help create a new visual arts program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He moved to the Boston area and bought a large house to hold bigger workshops for his students. He continued to explore how people understand photos and started using ideas from Gestalt psychology in his teaching. He even asked students to draw subjects as well as photograph them to help them understand "equivalence."

White began to have health challenges in 1966. This led him to focus even more on spiritual matters and meditation. His teaching methods became well-known for being unique. One student, who later became a Zen monk, said that White taught them "not only to see images, but to feel them, smell them, taste them."

In late 1966, White started writing the text for Mirrors, Messages, Manifestations. This was the first major book of his photographs. It was published by Aperture three years later. The book included 243 of his photos, along with poems and notes from his journal.

Over the next few years, White planned and directed four big photography exhibitions at MIT. He personally reviewed all the photos submitted for these shows.

White continued to teach and take photos even as his health declined. He spent more time writing and began a long text called "Consciousness in Photography and the Creative Audience." In 1970, he received a Guggenheim Fellowship to help him complete this work. He traveled to Puerto Rico in 1971 to explore color photography and to Peru in 1974 and 1975 to teach and continue his spiritual studies.

In 1975, White traveled to England to give lectures and teach classes. After a busy travel schedule, he had a heart attack and was hospitalized. After this, he took very few photos. He spent much of his time with his student Abe Frajndlich, who took many portraits of White. A few months before he died, White wrote an article where he connected himself to heroes from old stories, like Gilgamesh and King Arthur, who went on lifelong quests.

Minor White died on June 24, 1976, from a second heart attack at his home. He left his personal papers and a large collection of his photographs to Princeton University. He left his house to Aperture magazine so they could continue his work there.

His Impact

Understanding Equivalence

Minor White was greatly influenced by Alfred Stieglitz's idea of "equivalence." White believed that a photograph could mean more than just what it shows. He wrote that when a photo works as an Equivalent, it's both a record of something real and a "spontaneous symbol." This means it can make you feel something specific. For example, a photo of tree bark might make you feel a sense of strength or roughness inside yourself.

White often photographed rocks, waves, wood, and other natural things. He would show them in a way that made them look like abstract shapes. He wanted viewers to see these pictures as something deeper than just the object itself. He said, "When a photographer shows us an Equivalent, they are telling us, 'I had a feeling about something, and here is my picture that shows that feeling.'"

He explained that the photographer finds an object that, when photographed, will create an image with special power. This power can guide the viewer to a certain feeling or idea within themselves.

Photo Sequences

In the mid-1940s, White started to think a lot about how his photographs were shown. He learned from Stieglitz that photos shown together in a group can support each other. They can create a bigger, more meaningful message than each photo alone. When White worked at the Museum of Modern Art in 1945, he saw how Nancy Newhall arranged Edward Weston's photos. He said it was a big discovery for him.

For the rest of his life, White spent a lot of time arranging his photos into specific groups, called "sequences." These groups could have anywhere from 10 to over 100 pictures. He called a sequence a "cinema of stills." He believed it would create a "feeling-state" for the viewer, shaped by both the photographer and the person looking at the pictures.

In his early sequences, he included poems and other writings with his images. As his ideas developed, he stopped using text. At the same time, many of his photos became more and more abstract. He felt strongly about how his images were grouped. He wanted viewers to interpret his sequences in their own way, to gain insights about themselves.

Later, he became interested in how individual images affected a viewer based on how they were shown. In a work called Totemic Sequence, which had 10 photos, he used the same image at the beginning and the end. The last picture was the first picture turned upside down. White felt this showed how a photo could be both real and unreal at the same time. He called the first image "Power Spot."

White wrote a lot about his ideas on sequences in his journal and articles. He wrote that photos in a sequence are like a dance or a song. The main ideas are shown and repeated with changes until everyone understands them. He also wrote, "Sequence now means that the joy of photographing in the light of the sun is balanced by the joy of editing in the light of the mind."

During his life, White created or planned about 100 groups of his photographs. Many were simply called "Sequence" with a number. But for others, he gave artistic titles that showed his belief that photos mean more than what they seem.

Some of his important sequences include:

- Song Without Words (1947)

- Second Sequence: Amputations (1947)

- The Temptation of St. Anthony Is Mirrors (1948). This sequence was very personal. It used photos of a model named Tom Murphy.

- Sequence 11 / The Young Man as Mystic (1955)

- Sequence 13 / Return to the Bud (1959)

- Sequence 16 / The Sound of One Hand (1960)

- Sequence 17 / Out of My love for You I Will Try to Give You Back Yourself (1963)

- Slow Dance (1965). This sequence was different. It had 80 color slides meant to be seen with two projectors. It was inspired by his interest in movement.

- Totemic Sequence (1974)

Famous Quotes

- "At first glance a photograph can inform us. At second glance it can reach us."

- "Be still with yourself until the object of your attention affirms your presence."

- "Camera and I have gotten into some eye pursuit of intensified consciousness."

- "Equivalency functions on the assumption that the following equation is factual: Photograph + Person Looking Mental Image."

- "In becoming a photographer I am only changing medium. The essential core of both verse and photography is poetry."

- "One should not only photograph things for what they are but for what else they are."

- "When the photograph is a mirror of the man and the man is a mirror of the world, then Spirit might take over."

- "Everything has been photographed. Accept this. Photograph things better."

- "No matter how slow the film, Spirit always stands still long enough for the photographer It has chosen."

See also

In Spanish: Minor White para niños

In Spanish: Minor White para niños

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |