Miranda warning facts for kids

A Miranda warning is a special list of rights that people in the United States have. These rights protect you when the police want to ask you questions or when you are arrested. They are often called Miranda rights.

The police must tell you about these rights before they start questioning you. This rule came from a big decision by the Supreme Court of the United States in a case called Miranda v. Arizona in 1966.

The main goal of the Miranda warning is to make sure your rights are safe. These rights come from the Fifth and Sixth Amendments of the U.S. Constitution. It also makes sure you know about your rights and understand that you can use them.

Contents

Why We Have Miranda Rights

Important Court Decisions

The Sixth Amendment gives you the right to have a lawyer. Before the Miranda case, the Supreme Court made two other important decisions about this right.

In 1963, in a case called Gideon v. Wainwright, the Court said that anyone accused of a crime has the right to a lawyer. If they cannot pay for a lawyer, the government must give them one for free.

The next year, in Escobedo v. Illinois, the Court decided that if you are suspected of a crime, you have the right to have a lawyer with you while the police ask you questions.

The Miranda Case

The Supreme Court looked at the case of a man named Ernesto Miranda. The police had gotten a confession from him without telling him about his rights. The Court decided that the police had ignored his rights. So, they said his confession could not be used as evidence. (Even without that confession, Miranda was tried again and found guilty.)

The Court then made a new rule. Police must make sure suspects know and understand their rights before being questioned. This is why they give the "Miranda warning." It tells suspects they have these rights:

- The right to stay silent. You do not have to answer any questions.

- The right to have a lawyer. This includes a public defender, which is a free lawyer if you cannot afford one.

What the Miranda Warning Says

A common example of a Miranda warning you might hear is:

You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law. You have the right to an attorney. If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be appointed to you. Do you understand these rights as I have read them to you?

Many people know these words from television shows. But there is no single, exact way to say the Miranda warning. Different police departments and states use slightly different words. The Supreme Court says the words can change. However, the warning must always include four basic parts:

- You have the "right to remain silent." This means you do not have to say anything. You can refuse to answer any questions.

- Anything you say that is about a crime can be used as evidence in court. This evidence can be used to show you are guilty.

- You have the right to have a lawyer with you.

- If you cannot pay for a lawyer, you still have the right to one. The court will give you a free lawyer.

Different Ways to Say It

There are many different ways the Miranda warning is said, even just in English. Some versions try to be easier for young people or those with learning disabilities to understand. But studies have shown that these "simpler" versions can sometimes be even harder to understand for these groups.

The Miranda warning also needs to be translated into many languages. Police often carry cards with the warning in different languages. They might also use translators.

When Police Use the Warning

Police must give you a Miranda warning before they start asking you questions if you are in their custody. This means you are under arrest or not allowed to leave.

If police do not give the warning, or give it incorrectly, anything you say might be thrown out in court. This means a judge could rule that your confession or statements cannot be used as evidence in your trial.

For Miranda rights to be important in a trial, a few things need to be true:

- You said something to the police during questioning.

- You were in police custody (arrested or not free to leave).

- You knew the people asking questions were police officers.

- The government wants to use what you said in a criminal trial.

If these things are true, the prosecutor (the lawyer trying to prove guilt) must show that:

- You were given a Miranda warning.

- You understood your Miranda rights.

- You chose not to use your Miranda rights (this is called "waiving" them).

If the prosecutor cannot prove all of these, your statements might be thrown out.

Problems with the Miranda Warning

It Can Be Hard to Understand

Studies show that many versions of the Miranda warning are quite complicated. The more complex the warning is, the harder it is for people to understand.

For example, one study found that the average Miranda warning had sentences as complicated as instructions on United States tax forms. Some warnings were even harder to understand than a college-level accounting textbook!

Even "simplified" versions are not always easy. Some still require high school-level reading skills. To understand the most difficult Miranda warnings, a person would need a very high level of education, like a doctorate.

People Often Misunderstand

Many people think they understand their Miranda rights because they hear them on TV. But studies show that many people do not fully understand them. Some even have wrong ideas about them.

For example, one study found that many people thought if they did not answer questions, the court would use that against them. This is not true. You have the right to remain silent, and choosing to be silent cannot be used as proof of guilt.

Other studies show that most juveniles (children and teenagers), and even many adults, do not understand their rights well enough. They might not know when to use their rights or when to "waive" them (choose not to use them).

For example, in one study, researchers asked young people and adults to explain the Miranda warning in their own words. They found:

- Only about 1 out of 5 young people (20.9%) understood all four parts of the warning.

- More than half of young people (55.3%) did not understand at least one part of the warning.

- Young people who did not understand their rights were more likely to give them up.

- Children from poorer families were most likely to give up their rights.

Young People and Miranda Rights

No Supreme Court rule says that children must have a parent or lawyer with them when police question them. About 12 states have added extra protections for young people. For example, some states do not let young people give up their Miranda rights without a parent or guardian there. But most states do not have this rule. This means that in most states, young people can give up their rights on their own.

I am a police officer, your adversary, and not your friend.

– From a Miranda warning designed for young people in Missouri

A study in 2008 looked at Miranda warnings that were supposed to be simpler for young people. It found that these warnings were often longer than the adult versions. Some had over 500 words! They also required higher reading levels to understand.

Another study in 2013 found that 16- and 17-year-olds accused of serious crimes almost always gave up their Miranda rights. They did this 93% of the time, while adults did it 80% of the time. When young people give up their rights and talk to police without a lawyer, they are much more likely to confess to something they did not actually do. Studies have shown that about one-third to two-fifths of false confessions came from young people. Police got almost 7 out of every 10 of these false confessions from children aged 15 and younger.

The American Bar Association suggests this version of the Miranda warning for young people:

(1) You have the right to remain silent. That means you do not have to say anything. (2) Anything you say can be used against you in court. (3) You have the right to get help from a lawyer. (4) If you cannot pay a lawyer, the court will get you one for free. (5) You have the right to stop this interview at any time. (6) Do you want to have a lawyer? (7) Do you want to talk to me?

Language Barriers

Translating the Miranda warning into other languages can cause problems. There have been many cases where confessions were thrown out because of mistakes in giving the warning in other languages. For example, there have been lawsuits about:

- People who speak Arabic, Cantonese, Dinka, Korean, Mandarin Chinese, Somali, and Spanish being given Miranda warnings in English.

- Written warnings in Spanish and Brazilian Portuguese that were not translated correctly.

- Police using translators who made mistakes, did not know legal words, or did not speak the suspect's language well.

- Police using translators who did not speak the suspect's language at all.

It can also be hard to translate the Miranda warning into some languages. Not all languages have words for the same ideas as English. For example, American Sign Language has no signs for legal words like "rights."

Related pages

- Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution (protects the right to stay silent)

- Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution (protects the right to a lawyer)

- Gideon v. Wainwright (says everyone has the right to a lawyer for criminal charges, even a free one)

- Escobedo v. Illinois (says you have the right to a lawyer while police question you)

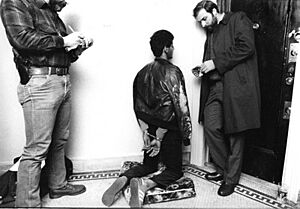

Images for kids

-

This is a page from the notes of Chief Justice Earl Warren about the Miranda v. Arizona decision. This page helped create the basic rules for the "Miranda warning."

See also

In Spanish: Advertencia Miranda para niños

In Spanish: Advertencia Miranda para niños