Mocedades de Rodrigo facts for kids

The Mocedades de Rodrigo is an old Spanish poem. It was written around 1360. This poem tells the exciting stories of the legendary hero El Cid (Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar) when he was young.

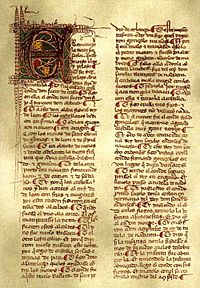

We have 1164 lines of this poem today. It also has a short introduction written in prose. The only copy of this work is a manuscript from the 1400s. It is kept in the National Library of Paris. The original text does not have a title. So, experts have given it different names over time. Some call it Mocedades de Rodrigo (Youthful Deeds of Rodrigo). Others call it Cantar de Rodrigo y el Rey Fernando (Song of Rodrigo and King Fernando).

Contents

Discover the Story: Plot of the Poem

The poem starts by talking about Rodrigo's family history. Then, it tells how young Rodrigo killed Count Don Goméz. This count was an enemy of Rodrigo's father. Don Goméz was also the father of Jimena Díaz.

To make things right, King Ferdinand ordered Rodrigo to marry Jimena. But Rodrigo refused! He said he would only marry her after winning five battles. This was a common story idea back then. It showed a hero putting off a duty to complete a hard mission.

In this version of the poem, the five battles are:

- A victory against the Moor Burgos de Ayllón.

- Winning against a champion from Aragon for the city of Calahorra.

- Defending Castile from sneaky counts.

- A battle against five Moorish allies.

- Moving the main church office (bishop's seat) of Palencia.

After these events, the King of France, the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, and the Pope demanded a shameful payment from Castile. This payment included fifteen noble young women every year. Rodrigo encouraged King Fernando to fight back. Together, they defeated the powerful group of the Count of Savoy, the King of France, the Emperor, and the Pope. The poem ends right after this huge victory, during the talks about their surrender.

Who Wrote It? Date and Author

Experts like Alan Deyermond believe the poem was written around 1360. It was likely written in the Palencia region. The author was probably an educated person, maybe even a priest. They think this author reworked an older, lost text from the late 1200s. This older text is known as "Gesta de las Mocedades de Rodrigo."

Older versions of the poem did not mention the Palencia church area. This suggests the poem was written to promote this area. It was a time of money and political problems. Connecting the famous Cid to Palencia's history helped bring people and money to the bishop.

Another expert, Juan Victorio, thinks the author was from Zamora. This author might have worked with the Palencia church. The poem shows the author knew a lot about old laws and family symbols. This theory is supported by some language from León in the poem. Also, the author knew small places in Zamora. The king's court is often in Zamora in the poem. Rodrigo also meets King Fernando in Granja de Moreruela (Zamora).

Victorio also points out that the author supported King Peter I the Cruel. This was during a war between Peter and his cousin, Henry II, from 1357 to 1369. The enemies of young Rodrigo in the poem are the same as King Peter's enemies in real life: Aragon, the French king, and the Pope. So, the author used this poem not just for the church, but also for political reasons.

Older Versions of the Story

There are signs that stories about Rodrigo's youth existed in the 1200s. These stories appear in old history books. For example, they are in the Chronicon mundi and the History of Spain. Later, around 1300, the Chronicle of the Kings of Castile had a more complete story. This story was missing from the Mocedades. Finally, a priest or educated writer put all these stories together around 1360. This is the version we know today.

The Chronicle of the Kings of Castile tells a story that came before the Mocedades. This earlier story is called "Gesta de las Mocedades de Rodrigo." It led to many popular songs (romances) about young Rodrigo. The "Gesta" was calmer than the poem we have now. Rodrigo was less rebellious in it. It also did not mention the Palencia church area. This difference made experts think the poem we have was written by someone from that area.

How it Sounds: Poem's Meter

The poem has about 30 groups of lines that rhyme. These lines do not have a fixed number of syllables. But they often have between 14 and 16 syllables. Each line is usually split into two parts. The first part often has eight syllables. This style is similar to Spanish popular songs (romances). Sometimes, the person who copied the poem wrote each part of a line on a separate new line.

The number of lines in each rhyming group changes a lot. Some groups have 264 lines, while others have only two. It is possible that many short groups are just parts of incomplete sections. This is because the poem has many missing parts.

How it's Built: Structure of the Poem

The poem has different stories that are not always strongly connected. It seems to be the last version made from many different sources. These sources include history books and oral stories. It might even include early Spanish songs about El Cid. This is clear because there are about a dozen missing parts in the text. Some of these gaps are very big. One big gap even stops the manuscript in the middle. So, we have to guess the ending based on other old history books.

The poem has several main parts:

- A history and family tree introduction in prose.

- Stories about the hero Fernán González.

- The story of Jimena's father dying and the wedding plans.

- Adventures and battles in Spain.

- Fights against Moors (like Burgos de Ayallón) and Christians (like the messenger from Aragon).

The poem also includes local church matters. For example, it talks about finding Saint Antoninus's crypt. It also mentions moving Bishop Bernaldo to his Palencia church office. At the same time, it includes big military campaigns. These include Ferdinand and Rodrigo fighting against the King of France, the Emperor, and the Pope. It feels like a lot of different stories were put together in this poem.

The first lines of the poem, which are in prose, were likely written by the person who copied the manuscript. This is because there are still hints of rhymes in these prose paragraphs.

Some experts think the poem should end with King Ferdinand becoming an emperor. Another idea is that it ends with Bishop Bernaldo returning to his church office. This ending would fit the idea that the poem was written to promote the church.

How it Compares: Medieval Spanish Epic Poems

The Mocedades and Epic Traditions

It is interesting that epic poems were still being written so late, in the second half of the 1300s. Epic poems were usually old stories passed down by word of mouth. By this time, people like Sir Juan Manuel were writing more modern literature. News was usually written in prose history books. So, why did the author choose to write in the old epic style?

Menéndez Pidal, a famous scholar, said that people already knew the Cid's adult adventures. So, they wanted to hear new stories about his childhood. He said:

Of any hero of primary interest are his most notable actions, those that brought an end during the plentitude [sic] of his strength; but later... this engenders a general curiosity to know a multitude of details that earlier were of no interest... To this curiosity the author of the Mocedades de Rodrigo tried to satisfy.

The Mocedades also uses common story ideas from folk tales. These are like the ones found in popular oral stories. One example is the hero putting off a promise. Another is the story of a prisoner escaping with a woman's help. Or the yearly payment of fifteen noble young women demanded by the Pope, Emperor, and King of France.

The author also knew about French epic poems. They mention characters like "Almerique de Narbona" and "Los Doçe Pares." French stories were very popular in Spain at this time. Many characters from French epics appear in Spanish popular songs.

The Hero's Character

In the Mocedades de Rodrigo, young Cid acts very differently from other stories about him. For example, in the Cantar de mio Cid, he is usually very polite and controlled. But in this poem, he is arrogant, boastful, and proud. Sometimes, he is even disrespectful to his king, Ferdinand.

One example is their first meeting. The king called Rodrigo and his father to suggest Rodrigo marry Jimena. This would make up for killing her father. But Rodrigo was suspicious:

"Listen, sayth I, friends, relatives and vassals of my father:

Guardeth thine Lord without deceit and without skill, If thou wish for the bailiff to apprehend him, for much would he want to kill him, How black a day findeth the king like the others that are there! Thou cannot say traitors for thou killeth the king..." Mocedades de Rodrigo, vv. 410-414

Later, he refused to recognize the king as his lord or kiss his hand. He said, "because thou, my father, I am spoiled." He also bravely talked back to the Pope. This happened when the Pope asked King Ferdinand if he wanted to be "emperor of Spain." Rodrigo stepped forward and spoke before his king could answer. This was not proper behavior.

Here spoke Ruy Díaz, before the king Sir Ferdinand:

"Thou giveth God bad thanks, oh Roman pope! We have come for that which is to be won, not that which is already won, Since the five kingdoms of Spain without you already kiss his hand: It remains to conquer the empire of Germany, which by right must be inherited." Mocedades de Rodrigo, vv. 410-414

This rebellious character was probably meant to surprise and entertain the audience. It shows how stories were becoming more imaginative in the 1300s.

However, Juan Victorio believes that heroes in Spanish epics were often rebellious. He points to stories like those of Bernardo del Carpio or Fernán González. This rebellious nature is also common for heroes in Spanish popular songs.

Why it's Important: Valuation

For a long time, the Mocedades was not seen as a very important literary work. But from a history of literature point of view, it is extremely interesting.

First, it is the last known medieval Spanish epic poem. This means the old epic style lasted until the late 1300s. This helps us understand how these old works were dated.

Second, this poem started the tradition of popular songs (romances) about El Cid's youth. One part of the story, where the hero kills Jimena's father, led to a play by Guillén de Castro, Las Mocedades del Cid. This play then inspired the famous drama Le Cid by Corneille.

The Mocedades is the last surviving example of a Spanish chanson de gesta (epic song). It is believed that Spanish popular songs (romances) came from this type of poem. The Mocedades is similar to these songs because it is imaginative. Also, most of its lines have eight syllables. If you just put each part of a line on a separate new line, and consider the missing parts, you can see how Spanish popular songs developed. They have rhyming eight-syllable pairs, start in the middle of the action, and often have sudden endings. They also add a lot of made-up stories to historical events.

Where to Find It: Editions of the Mocedades de Rodrigo

Old Manuscripts

- Manuscript number 12, in the National Library of Paris.

Modern Books

- Francisque Michel and J.F. Wolf, in Wiener Jahrbücher für Literatur, Vienna, 1846.

- Agustín Durán, Biblioteca de Autores Españoles (BAE), volume 16, 1851.

- Damas Hinard, in Poëme du Cid, Paris, 1858.

- A.M. Huntington (facsimile edition), New York, 1904.

- B.P. Bourland, in Revue Hispanique, 24 (I), 1911, pp. 310–357. (called Rhyming Chronicle of El Cid)

- Ramón Menéndez Pidal, in Reliquias de la poesía épica española, Madrid, Espasa-Calpe, 1951, pp. 257–289. (called Cantar de Rodrigo y el rey Fernando)

- A.D. Deyermond (paleographic edition) in Epic Poetry and the Clergy: Studies on the "Mocedades de Rodrigo", London, Tamesis Books, 1969.

- Juan Victorio, Madrid, Espasa-Calpe, 1982.

- Leonardo Funes with Felipe Tenenbaum, eds. Mocedades de Rodrigo: Estudio y edición de los tres estados del texto, Woodbridge, Tamesis, 2004.

- Matthew Bailey, ed. & translator, Las Mocedades de Rodrigo, The Youthful Deeds of Rodrigo, the Cid, Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 2007.

See also

In Spanish: Mocedades de Rodrigo para niños

In Spanish: Mocedades de Rodrigo para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |