Morgan Report facts for kids

The Morgan Report was a special investigation by the U.S. Congress in 1894. It looked into what happened when the Hawaiian Kingdom was overthrown. This included checking if U.S. military troops played a part in removing Queen Liliʻuokalani from power.

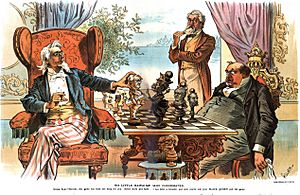

This report, along with the Blount Report from 1893, is a key document. It gathers statements from people who saw or were involved in the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom in January 1893. The Morgan Report was the final result of this official U.S. Congressional investigation. It was led by the United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, whose chairman was Senator John Tyler Morgan.

The report is officially known as Senate Report 227. It was finished on February 26, 1894.

Contents

What Was the Morgan Report?

The Blount Report had said that the U.S. Minister to Hawaii, John L. Stevens, acted improperly. It claimed he landed U.S. Marines without good reason to help those who wanted to remove the queen. The Blount Report stated these actions helped the overthrow succeed.

However, the Morgan Report disagreed with the Blount Report. It found that almost everyone involved in the overthrow was "not guilty." The only exception was Queen Liliʻuokalani herself. A later report from 1993, the Native Hawaiians Study Commission Report, said that "The truth lies somewhere between the two reports."

The Morgan Report came out around the same time as the Turpie Resolution. This resolution stopped President Cleveland's attempts to put the Queen back in charge. President Cleveland accepted what the Morgan Report said. He continued to work with the new government, called the Provisional Government. He also recognized the Republic of Hawaii when it was created on July 4, 1894.

The nine members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee could not fully agree on the report's final conclusion. The main summary, which is often mentioned, was only signed by Senator Morgan. Other members generally agreed but had some disagreements about certain parts.

Why Was the Report Created?

The Morgan Report was the final outcome after President Cleveland asked Congress to look into the overthrow.

President Cleveland explained why he sent the matter to Congress. He felt that the problems in Hawaii and the U.S. made it hard for him to solve the issue alone. He believed Congress, with its wider powers, should handle it. He sent all the information he had, including the Blount Report and witness statements. He promised to help with any plan Congress came up with, as long as it was fair and honorable for the U.S.

Historical Events Leading to the Report

When the Hawaiian Kingdom was overthrown, President Benjamin Harrison was nearing the end of his term. He was a Republican who supported expanding U.S. influence. The new government in Hawaii, called the Provisional Government of Hawaii, quickly sent a treaty of annexation to President Harrison. He sent it to the Senate for approval on February 15, 1893.

However, Grover Cleveland, a Democrat, became President on March 4, 1893. He was against expansion and taking over other countries. So, he pulled the treaty back from the Senate on March 9, 1893.

President Cleveland then appointed James Henderson Blount as a special envoy to Hawaii. Blount was given special powers and secret instructions to investigate the revolution. He was to find out how stable the new Provisional Government was.

Blount spoke secretly with people who supported the queen and those who wanted Hawaii to join the U.S. He also took formal statements from some witnesses. These statements were not sworn under oath. Blount delivered his report to President Cleveland on July 17, 1893. He claimed that improper U.S. support was responsible for the revolution's success. He also said the Provisional Government did not have much public support.

Based on Blount's report, President Cleveland tried to put the Queen back in power. This was conditional on her forgiving those who overthrew her. However, the Queen initially refused to grant amnesty.

On December 18, 1893, President Cleveland gave up on convincing the Queen to grant amnesty. He sent a message to Congress saying the revolution was wrong. He also said the U.S. was involved in it. He then referred the whole matter to Congress.

In response, the Senate decided to hold public hearings. They wanted to investigate U.S. involvement in the revolution. They also wanted to see if President Cleveland was right to appoint Blount with such special powers.

The Morgan Report was the final result of this investigation. It was submitted on February 26, 1894.

What Happened After the Report?

The Turpie Resolution, passed on May 31, 1894, was a direct result of the Morgan Report. Queen Liliʻuokalani protested this resolution. But it ended all her hopes for the U.S. to help her regain her throne.

President Cleveland's Final View

President Cleveland accepted what the Congressional committee decided. He stopped trying to put the Queen back in power. He treated the Provisional Government and the Republic of Hawaii as the rightful governments after the Kingdom of Hawaii. Even though he had strong words in December 1893, he never again questioned the overthrow's legality after the Morgan Report and the Turpie Resolution.

Main Findings of the Committee

The main report included these conclusions:

- There was a situation in Honolulu that made people fear violence. This could put American citizens' safety at risk. This had happened before when Hawaii's government changed.

- The Queen tried to change the constitution of 1887. She had sworn to follow this constitution. Many people saw this as a violation of her duties. They thought it was a revolutionary act. They believed it meant she had given up her power. This situation made the Hawaiian government unable to protect American citizens and other foreigners.

- When U.S. troops landed from the ship Boston, they did not act in a hostile way. They were quiet and respectful. They had landed many times before for drills. As they passed the palace, the Queen appeared. The troops saluted her respectfully. They showed no sign of wanting to fight.

- The committee agreed that Hawaii's government was in a difficult state when the troops landed. There was no clear leader to enforce laws. The U.S. had the right to land troops to protect its citizens if its minister thought it was necessary.

- Later, on February 1, 1893, the American minister raised the U.S. flag over a government building in Honolulu. He declared that the U.S. was protecting Hawaii. This action by the minister was done without permission. It was later canceled by U.S. officials. The order to take down the flag was the right thing to do to protect the honor of the United States.

A smaller report by the four Republican senators criticized Blount's appointment and actions.

Another smaller report by four Democratic senators criticized Minister Stevens for his actions.

However, all the senators agreed that the U.S. military acted neutrally.

Here's how the senators voted on key topics:

- 9–0: The U.S. military acted neutrally.

- 5–4: Blount's appointment was constitutional (Morgan and his fellow Democrats agreed).

- 5–4: Stevens' actions were justified (Morgan and four Republicans agreed).

Members of the Committee

Republicans

- John Sherman

- Joseph N. Dolph

- William P. Frye

- Cushman K. Davis

Democrats

- John Tyler Morgan

- Matthew Butler

- David Turpie

- John W. Daniel

- George Gray