Moroccan citron facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Moroccan citron |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Species | Citrus medica |

The Moroccan citron (Hebrew: אֶתְרוֹג מָרוֹקָנִי) is a special type of citron fruit. It originally comes from a village called Assads, Morocco, which is still the main place where it is grown today.

Contents

A Sweet Citron

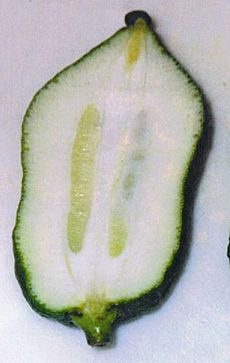

A Moroccan professor named Henri Chapot described the Moroccan citron as a sweet citron. This means its inside fruit part, called the pulp, has very little acid.

Professor Chapot found that most common citrons or lemons have red color on the inner part of their seeds, purple on their flower blossoms, and reddish-purple new buds. This red color shows they are acidic. The Moroccan citron, which is sweet and not acidic, does not have these red colors at all.

This discovery was even mentioned by famous citrus experts, Herbert John Webber and Leon Dexter Batchelor, in their important book, The Citrus Industry, published in 1967.

Chapot was likely the first to describe this citron in great detail. He included pictures of the fruit and explained all about the plant, its leaves, and flowers. He also noted that the true Moroccan citron, grown only in Assads for a special Jewish holiday, is long, not acidic, and a bit dry. This is very different from another rounder citron called Rhobs el Arsa, which is grown more for food in Morocco and tastes acidic and fruity.

The only other known sweet citron is the Corsican citron.

Used as an Etrog

The Moroccan citron has been used as an etrog for a very long time. An etrog is a special fruit used in the Jewish holiday of Sukkot. According to Jewish people in Morocco, they have been using this citron since ancient times, after the Second Temple was destroyed.

Over time, this citron became highly respected by rabbis and Jewish communities across North Africa. Later, it was also accepted by Ashkenazi communities in Europe.

Where it is Grown

The Moroccan citron is grown in the village of Assads, Morocco, which is in the Taroudant Province. This area is about 100 kilometers (62 miles) east of Agadir. Many religious and non-religious sources have confirmed this location.

No Grafting

For the Jewish holiday of Sukkot, citrons that have been grafted are not allowed for ritual use. Grafting is when parts of two plants are joined together to grow as one. Some people prefer to use etrog citrons that have never been grafted, and whose parent plants were also never grafted.

In 1995, Professor Eliezer E. Goldschmidt and a group of rabbis were asked by Rabbi Yosef Shalom Eliashiv from Jerusalem, Israel, to check if the Moroccan citrons were still pure and if any grafted ones could be found there. Goldschmidt asked a Moroccan horticulture professor, Mohamed El-Otmani, to help them.

They all climbed into the Anti-Atlas canyon where the local Berbers have been growing the Moroccan citron for many centuries. They were very impressed by the old traditions practiced there and found no grafted citron trees.

The group shared their findings with Rabbi Eliashiv, who was very pleased to hear that the Moroccan wild areas still had a pure line of non-grafted etrogs.

Few Seeds

In 1960, a well-known etrog grower named Schraga Schlomai raised concerns about other types of etrogs. He claimed that the Diamante citron and Greek citron might not be pure because some of them were known to be grafted. He argued that if some were grafted, it was hard to be sure about the others.

He also said that even though no grafted trees were found among Moroccan and Yemenite citrons, they might not be suitable because they looked different from the traditional types. The Moroccan citron was said to have very few seeds, and the Yemenite citron was said to have little pulp. These differences, he argued, made them too unlike the traditional etrogs.

However, Rabbi Shmuel David Munk disagreed. He wrote that if the citrons were definitely not grafted, their different appearance should not make them unsuitable. He believed that an etrog from one country does not have to look exactly like one from another.

In 1980, when the Moroccan citron became very popular in New York City, Rabbi Yekusiel Yehudah Halberstam (the Klausenberger Rebbe) brought up Schraga Schlomai's concerns again. He decided that the Moroccan citron should not be used for religious purposes. His reason was that some of them had no seeds. He believed that an authentic citron should always have seeds, especially since old religious texts discuss the direction seeds should face to prove a citron's purity.

However, when seeds are present in the Moroccan citron, they actually point straight up, which is the required direction. Also, the fact that some have few seeds cannot be because of grafting, as the trees have been checked many times and found to be completely free of any grafting.

Pure Genetics

Some people wondered if natural mixing with other plants might have changed the Moroccan citron's genetic makeup or its appearance. However, DNA tests done by Elizabetta Nicolosi from the University of Catania, Italy, and other researchers, showed that the Moroccan citron is a completely pure citron. It is also very similar to other pure etrogs used for the holiday.

Images for kids

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |