Greek citron facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Variety Etrog |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Species | Citrus medica |

The Greek citron is a special kind of citron fruit. It's known for its use in a Jewish ritual called the etrog during the Sukkot holiday. Because of this, it was officially named the "variety etrog" by a scientist named Adolf Engler.

People also called it pitima or cedro col pigolo, which means "citron with a pitom". A pitom is a small, stick-like part that usually stays on top of this fruit. Having a pitom makes the fruit special and important for the religious ritual.

Contents

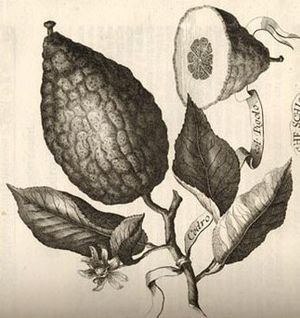

What the Greek Citron Looks Like

In 1708, a person named Johann Christoph Volkamer described this citron in his book. He grew it in his botanical garden in Nuremberg, Germany. He called it the "Jewish Citron" because it was mainly used for the Jewish holiday of Sukkot.

Here's what he said about it: This citron tree doesn't grow very big. Its leaves are smaller than other citrons, and they are jagged, long, and pointed. The tree has many thorns. The flowers are small and look reddish on the outside.

The fruit starts out reddish and dark green. Then it turns completely green, and when it ripens, it becomes straw-yellow. These fruits stay quite small and never grow as large as other types of citron.

The fruit has a point at the top with a small, long "pitom" (the stick-like part). It smells very pleasant, like another citron called the Florentine citron. This fruit has very little juice and tastes a bit sour and bitter. It seems to grow better in pots than in the ground.

How It Was Used and Grown

The Greek citron was first grown in towns near Corfu, an island in Greece. Jewish leaders in Corfu watched over the etrogim (plural of etrog). These fruits were then sent to Trieste, a city in Italy, through Corfu. This is why Jewish people called them the Corfu etrog.

Today, you can still find citron trees on Corfu and in Naxos, another Greek island. However, citrons from Greece are no longer sent out for religious purposes. Citron growers in Crete sell their fruit to be made into succade, which is candied citron peel. In Naxos, the citron is used to make a special, fragrant liqueur called kitron.

The Greek Citron as an Etrog

Its Early History

According to a Jewish community called the Romaniotes, they had this type of citron since the time of the Second Temple (a very old Jewish temple) or even earlier. They always used it for their religious rituals. Later, Sephardi Jews who moved to Italy, Greece, and Turkey after being forced out of Spain in 1492 also began to value it.

Many writers believe that Alexander the Great's soldiers first brought the citron to Europe. The philosopher Theophrastus, who took over Aristotle's role at the Botanical garden in Athens, also described it.

In Ashkenazi Communities

When Corfu etrogim started arriving in other parts of Europe in 1785, some Jewish communities, especially those following Ashkenazi traditions, were unsure about them. These communities usually used a different type of citron called the Genoese variety. The Ashkenazim worried that the Greek citron might have been changed by grafting (joining parts of two plants) or hybridizing (mixing two plant types).

In the early 1800s, the supply of the Genoese citron became difficult because of the wars led by Napoleon I of France. This allowed the Greek citron to become very popular in the market.

A rabbi named Ephraim Zalman Margolis wrote that the Corfu etrogim at that time were not grafted. He said that even if it was hard to know their exact history, they should still be considered acceptable for the ritual. He concluded that if a good, acceptable Genoese etrog couldn't be found, the Corfu etrog could be used instead. This decision helped make the Greek etrog more widely accepted.

New Growing Areas

In 1846, a merchant named Alexander Ziskind Mintz claimed that only citrons grown in Parga, Greece, were not grafted and therefore acceptable for the ritual. He said that under the old Ottoman Empire rules, citrons could only be planted in Parga under strict control, and these were known to be pure.

However, the local Sephardic rabbis, led by Judah Bibas, the Chief Rabbi of Corfu, insisted that all the citrons grown in the region were acceptable and that no grafted trees were used. Rabbi Chaim Palagi from İzmir, Turkey, supported their view.

This disagreement eventually led to some rabbis banning all Greek citrons, while others allowed them if they had a certificate from local rabbis.

The Monopoly and Its End

Despite the arguments, the Corfu etrog remained very common. In 1875, the growers formed a group and sharply increased the price of each etrog, thinking that Jewish people would have no choice but to pay.

There was a false idea that Jews believed they wouldn't survive the next year if they didn't use a Corfu etrog for Sukkot. This was not true. Rabbi Yitzchak Elchanan Spektor of Kovno wanted to stop this price control. He banned the Corfu etrog until prices dropped and its purity was confirmed. Even the rabbi of Corfu wrote that many grafted trees were in the region, making it hard to certify them. Many leading rabbis in Eastern Europe supported this ban.

Because of this, the Balady citron from Israel, which was just starting to be imported, became the preferred choice. Even the Corsican citron was chosen over the Corfu, while the highly respected Genoese citron was very hard to find.

Jewish etrog merchants promised their local rabbis that they would not buy from the Greek farmers. This was a big sacrifice for the Jewish community in Corfu, who lost income that year. This action severely affected the Greek growers, forcing them to lower their prices.

Decline of the Greek Citron

As a result, the Greek citron became much less popular in Eastern Europe, where people switched to the Balady etrogs. However, it was still used in other places. After World War II, some European Jews who moved to Israel or the United States continued to use the Greek citron for about twenty years.

In 1956, Rabbi Yeshaye Gross from Brooklyn visited the citron orchards in Calabria, Italy. He found that many trees there were grafted. From then on, he realized that every etrog needed careful checking before being picked.

In contrast, the Greek growers did not allow Jewish merchants to visit their orchards to inspect the trees. They only sold etrogs in Corfu. This made many Satmars (a Jewish group) switch back to the traditional Yanova citron, even if it didn't have a pitom. Growing the Greek citron then focused on Halki and Naxos, mainly for making liqueur.

Around this time, the Moroccan citron became popular. It was known for being pure, without any history of grafting, and for having a strong, healthy pitom.

Still, the Skverer rebbe (a Jewish leader) manages to get one etrog from Corfu every year.

Introduction to Israel

Around 1850, Sir Moses Montefiore helped set up etrog farms in the Holy Land (Israel) to support Jewish settlers. The Balady citron grown there wasn't always the best shape or color, and only a few had a pitom. So, Sephardi Jews who liked the Corfu etrog planted its seeds in the coastal area of Israel, especially near Jaffa. A local rabbi confirmed that this planting was acceptable.

Arab farmers brought cuttings from Greece. They grafted these onto other plant roots, like the Palestinian sweet lime, to make them healthier and live longer. The Corfu variety, which they called kubbad abu nunia (citron with a pitom), didn't grow well in the land of Palestine on its own. So, growers started using grafting a lot.

A scholar named Rabbi Aaron Ezrial still certified some pure citron orchards in Jaffa by removing any grafted plants he found. Many Sephardic and even some Ashkenazic rabbis supported the Greek-Jaffa citron because it was beautiful and had a pitom. This was allowed if every tree was inspected before picking, just like it is done in Calabria today.

Over time, the Greek citron from Jaffa became more popular than the Balady citron. The Jaffa Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook started a group called "Atzei Hadar" to help grow and sell acceptable etrogs. He wanted to prevent grafting the Jaffa etrog onto roots of sour orange or sweet lime, but he strongly supported grafting the Greek citron onto Balady citron roots. This type of grafting is allowed by Jewish law.

This led to a beautiful and acceptable variety of citron in Israel, which helped the country's economy for many years. Today, it is the main variety grown in Israel and is important in international trade.

Questions About Purity

Even though grafting the Greek citron onto Balady roots was a good idea, it made some people wonder why the Israeli citron suddenly looked so beautiful with an upright pitom. Rumors spread in Israel and other Jewish communities.

The Grand Rabbi of Munkatch, Chaim Elazar Spira, noticed this change. He thought it might be the same problem that was often claimed against the Greek citron in Greece: that it was grafted or mixed with lemon, which would make it unacceptable for the ritual.

This wasn't entirely wrong, because some citrons that weren't supervised were indeed grafted onto bitter orange or limetta roots. Also, even with supervision, it's very hard to tell what kind of rootstock was used if it's not the same as the top part of the plant.

Other rabbis, like Solomon Eliezer Alfandari and Ovadia Yosef, also had doubts about the beautiful Greek-Israeli citron.

Later, a pure, ungrafted tree was found in the backyard of a Jewish ritual slaughterer in Hadera, Israel. It was called ordang. Today, most Hasidic communities in Israel and other countries use descendants of this ordang type, which are grown under rabbinical supervision.

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |