Citrus taxonomy facts for kids

The botanical classification of the species, hybrids, varieties and cultivars belonging to the genus Citrus is called "citrus taxonomy".

Citrus taxonomy is how scientists organize and name different types of citrus plants. This includes all the different kinds of citrus fruits we eat, as well as their wild relatives. It's a bit like creating a family tree for all citrus fruits.

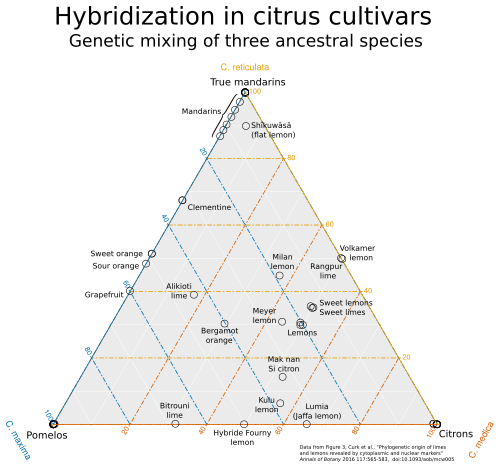

Understanding citrus families can be tricky. Many citrus fruits we know are hybrids. This means they are a mix of two or more original wild citrus types. For example, an orange is a mix of a mandarin and a pomelo! Citrus plants can easily mix their genes, even if they look very different. Sometimes, fruits that look alike might have very different family histories. Also, fruits that look different might be almost identical genetically, differing only by a small natural change called a bud mutation.

Scientists have studied the genes of wild and farmed citrus plants. They found that modern citrus started in the Himalayan mountains. From there, they spread quickly across South and East Asia and Australia. This led to at least 11 wild citrus species. Most of the citrus fruits we eat today are hybrids. They come from mixing these wild species, especially citrons, mandarins, and pomelos.

Most hybrid citrus plants do not grow true to type from seeds. This means if you plant a seed from a hybrid orange, you might not get an orange tree. Instead, they usually need to be grown from cuttings or by grafting. However, some hybrids can produce seeds that grow into plants just like the parent. This happens through a special process called apomixis.

Contents

The Citrus Family Tree: How They Are Related

All wild citrus species come from a single ancestor. This ancestor lived in the Himalayan foothills a very long time ago. The climate became drier, allowing citrus plants to spread quickly across Asia. Later, they spread to Australia, leading to new Australian species.

Most modern citrus fruits are hybrids. This means they are mixes of a few original, "pure" species. Scientists have identified about ten main ancestral citrus species. Seven of these are from Asia:

- Pomelo (Citrus maxima)

- 'Pure' mandarins (C. reticulata)

- Citrons (C. medica)

- Micranthas (C. micrantha)

- Ichang papeda (C. cavaleriei)

- Mangshanyegan (C. mangshanensis)

- Oval kumquat (Fortunella margarita or C. japonica var. margarita)

Three ancestral species are from Australia:

- Desert lime (C. glauca)

- Round lime (C. australis)

- Finger lime (C. australasica)

More recent studies have added two more pure species: the Ryukyu mandarin from Japan and the mountain citron from Southeast Asia.

How Citrus Plants Mix and Create New Types

Citrus plants can easily cross-pollinate with each other. This means pollen from one type of citrus can fertilize another. This ability to mix genes helps create many new varieties. Natural changes in their genes (mutations) also lead to new types.

The three most important ancestral citrus types are the citron, pomelo, and mandarin. These three types can mix freely, even though they grew in different parts of the world. Citrons grew in northern Indochina, pomelos in the Malay Archipelago, and mandarins in Vietnam, southern China, and Japan.

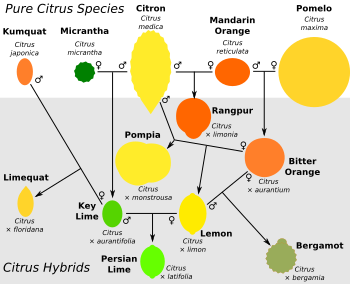

When these three main types mix, they create many familiar citrus fruits. These include:

Sometimes, these hybrids mix again with other citrus types. For example, the Key lime is a mix of a citron and a micrantha. Many of these new varieties are grown from cuttings, not seeds, to keep their special traits. This mixing and re-mixing makes the citrus family tree very complicated!

Kumquats usually don't mix naturally with other main citrus types because they flower at different times. But people have created hybrids like the calamansi by hand. Australian limes also didn't mix naturally with Asian citrus. This is because they are native to Australia and Papua New Guinea. However, modern plant breeders have crossed them with mandarins and calamansis.

People have also created new citrus fruits on purpose. They do this by:

- Planting seeds from natural mixes (like clementines).

- Finding and growing new changes (mutations) in existing hybrids (like the Meyer lemon).

- Crossing different varieties together (like the 'Australian Sunrise', a mix of finger lime and calamansi).

Naming Citrus: A Tricky Business

At first, many different citrus types were named by different scientists. This led to a huge number of names – over 870 species by 1969! Two main systems tried to organize them: the Swingle system and the Tanaka system. These systems were very different.

Swingle's System

Walter Tennyson Swingle's system was simpler. He grouped citrus into "true citrus" and related plants. He put most common citrus like citrons, pomelos, mandarins, oranges, grapefruits, and lemons into one main group. He only recognized about 16 main species, and then divided them into varieties or hybrids. This system is still used a lot today, but with many changes.

Tanaka's System

Chōzaburō Tanaka's system was much more complex. He gave a separate species name to almost every single type of citrus, even if it was a hybrid. This meant he identified 159 species! This system is like "splitting" everything into tiny groups. It's still used in Tanaka's home country, Japan.

Modern Naming Challenges

Scientists later realized that most citrus fruits are actually hybrids of just three species: citron, mandarin, and pomelo. This made the old naming systems even more confusing. For example, Swingle put kumquats and Australian limes into separate groups, but genetic studies show they are actually part of the main Citrus family.

In 2020, a new system was suggested by Ollitrault, Curk, and Krueger. Their goal was to make naming simpler and match the new genetic information. In their system, each original ancestral species has its own name. Then, any mix of these ancestral species gets a unique hybrid species name. Individual types of these hybrids are then called varieties.

For example, any hybrid that is a mix of mandarin (C. reticulata) and pomelo (C. maxima) would be called C. × aurantium. Then, specific types would be:

- C. × aurantium var. sinensis for the sweet orange.

- C. × aurantium var. paradisi for grapefruit.

- C. × aurantium var. clementina for the clementine.

This system helps show the genetic history of each fruit. However, it mainly focuses on the four species that created most commercial hybrids. It also needs full genetic information, which isn't available for all citrus types.

Main Citrus Species and Their Hybrids

Most citrus fruits we buy come from one or more of the 'core species': citrons, mandarins, and pomelos. These core species have special flowers that lead to more complex fruits. They have also created many hybrids, but their names can be confusing.

Sometimes, the same common name is used for different types of citrus. For example, many green fruits are called 'limes', but they can be very different genetically. Australian limes, musk limes, Key limes, and kaffir limes are all genetically distinct. Also, fruits with similar family histories can look and taste very different. For example, grapefruit, common oranges, and ponkans are all mixes of pomelo and mandarin.

Many traditional citrus groups, like sweet oranges and lemons, seem to be "bud sports." These are groups of plants that came from a single hybrid ancestor through natural changes. New varieties, especially those without seeds, have also been created by using radiation to cause new changes in these hybrid plants.

Ancestral Species: The Building Blocks

Mandarins

Mandarin oranges (like tangerines and satsumas – Citrus reticulata) are one of the basic species. But the name "mandarin" is also used for many small, easy-to-peel citrus fruits, including many hybrids. Genetic studies suggest there is only one main Asian mandarin species, Citrus reticulata.

Scientists have found that domesticated mandarins fall into two groups. These groups came from different wild mandarin populations and were farmed separately. One group is called 'common mandarins'. The other is called mangshanyeju (Mangshan wild mandarins). It was in the mangshanyeju that a genetic change allowed these mandarins to reproduce without seeds. This trait was then passed down to their hybrid children, like hybrid mandarins, oranges, lemons, and grapefruit.

A different group of mandarins comes from Japan and nearby islands. One of these, the Tachibana orange, was first thought to be a type of mainland mandarin. However, a study of these island fruits found a second true mandarin species called C. ryukyuensis. This species separated from the mainland mandarins millions of years ago when sea levels rose. Unlike the mainland species, the Ryukyu mandarin reproduces sexually (with seeds). The other island mandarins, including the Tachibana, are either natural first-generation hybrids or later farm hybrids.

All the commercial varieties we call mandarins are actually mixes of different species. Scientists divide mandarins into three types based on how much they are mixed. Some are genetically pure mandarins. A second type are mixes with pomelos that were then bred back with mandarins. This keeps only a few pomelo traits. The third type came from mixing these hybrids again with pomelos or sweet oranges. This creates mandarins with more pomelo DNA. Some commercial mandarins are also mixes with lemons, and some have a lot of papeda genes.

The 'Mangshan wild mandarin' name is used for similar-looking wild mandarin fruits from the Mangshan area. But it actually includes two genetically different groups. One is a pure, wild "true" mandarin. The other is a distinct and only distantly related species, the mangshanyegan (C. mangshanensis). This mangshanyegan is the most distant relative of all citrus plants.

Pomelos

The pomelo (Citrus maxima) is another core species. Most citrus hybrids come from it. It is native to Southeast Asia. In hybrids that are mixes of mandarin and pomelo, the more pomelo DNA a fruit has, the bigger it is. The tastier mandarins are those that got specific genes from pomelos that change their sourness. Some common pomelos are genetically pure. Others have a small amount of mandarin DNA from a mix that was then bred back many times with pomelo.

Citrons

True citrons (Citrus medica) come in very different shapes. The citron usually self-pollinates, meaning it fertilizes itself within an unopened flower. This leads to very little genetic variety in citrons. Because of this, it usually acts as the male parent in any hybrid mixes. Many citron varieties have been shown to be non-hybrids, even with their very different looks. However, the florentine citron is probably a hybrid.

Genetic studies of citrons show they divide into three groups:

- Wild citrons from China that have pulp and seeds.

- Fingered citrons, also from China, which are mostly seedless and must be grown artificially.

- Mediterranean citrons, which are thought to have come from India.

Some fingered citron varieties are used in religious offerings. Some common varieties are used as the etrog in the Jewish harvest festival of Sukkot. The Mountain citron is a complex citrus hybrid that has only tiny amounts of true citron.

Papedas

Swingle created the name Citrus subgenus Papeda for citrus types that were less edible. He included the kaffir lime (Citrus hystrix), micrantha (Citrus micrantha), and Ichang papeda (Citrus cavaleriei) in this group. However, genetic studies show that these species are not closely related enough to be in the same group. Both the micrantha and the Ichang papeda have also mixed with other citrus types to create hybrids. The mountain citron, which is not related to true citrons, was sometimes included here. It was later found to be a pure species most closely related to kumquats.

Kumquats

Kumquats were first classified as Citrus japonica. Later, in 1915, Swingle put them in their own separate group called Fortunella. He divided kumquats into different types. Since kumquats can handle cold weather, there are many hybrids between common citrus and kumquats. Swingle even made a special hybrid group for these, called × Citrofortunella.

Later studies showed that kumquats are actually part of the main Citrus family. So, scientists are now putting kumquats back into the Citrus genus. However, naming individual kumquat species is still debated. The Flora of China treats all kumquats as a single species, Citrus japonica.

Australian and New Guinean Species

Australian and New Guinean citrus species were also thought to be in separate groups by Swingle. However, genetic studies show they are part of the Citrus family, most closely related to kumquats. This means they should all be included in the Citrus genus. Scientists found three species among those tested: desert lime (C. glauca), round lime (C. australis), and finger lime (C. australasica). Other species like the New Guinea wild lime, Clymenia, and Oxanthera (false orange) also belong in the Citrus genus.

The outback lime is a desert lime chosen by farmers for better traits. Some commercial Australian limes are also mixes with mandarins, lemons, or sweet oranges. Clymenia can mix with kumquats and some limes.

Trifoliate Orange

The trifoliate orange is a cold-hardy plant that has leaves with three leaflets and loses its leaves in winter. It is close enough to the Citrus genus to be used as a rootstock for grafting. Swingle moved the trifoliate orange into its own group, Poncirus. However, some scientists believe it should be reunited with Citrus. Genetic studies have given mixed results, so there is still debate about where it belongs.

A second trifoliate orange, Poncirus polyandra, was found in China in the 1980s. Some scientists think it's a hybrid, but recent genetic analysis shows it's not.

-

Mandarin orange is a true species (Citrus reticulata); it is one of the progenitors of most cultivated citrus

-

The pomelo (Citrus maxima)

-

Three varieties of etrogim (Citrus medica acceptable for Jewish ritual use) that are all true non-hybrid citrons

-

The Australian desert lime, Citrus glauca, hangs from a branch

Citrus Hybrids: New Fruits from Mixing Genes

Citrus hybrids are many different types of citrus created by plant breeders. They are chosen for useful fruit traits, plant size, or how well they handle cold. Some citrus hybrids happened naturally, while others were created on purpose. This is done by mixing pollen from two different citrus types and choosing the best offspring. The goal is to get traits that are a mix of the parents, or to add a good trait from one parent to another.

In older naming systems, citrus hybrids often got unique names, marked with a multiplication sign (×) before the name. For example, the Key lime is Citrus × aurantifolia. They can also be named by joining the names of the parent species, like sunquat – C. limon × japonica. However, it can be hard to know the exact parents of some hybrids. Also, genetic tests show some hybrids come from three or more ancestral species. In the new Ollitrault system, a hybrid gets a species name based on its ancestral parents, plus a unique variety name.

Naming Hybrids: Why It's Confusing

Naming hybrids is often inconsistent. There's disagreement about whether to give hybrids their own species names. Even modern hybrids with known parents are sold under common names that don't tell you much about their family history. This can be a problem for people who can't eat certain citrus types. For example, some medications react badly with chemicals in grapefruit and Seville oranges. Many common citrus varieties are related to grapefruit or pomelo. Some doctors advise avoiding all citrus juice when on certain medications, though not all citrus fruits have these problematic chemicals. Citrus allergies can also be specific to only some fruits.

Major Citrus Hybrids You Might Know

Here are some common citrus hybrids that are sometimes treated as their own species:

- Orange: This name is used for several different mixes of pomelo and mandarin orange. They have the orange color of the mandarin and are easier to peel than pomelos. Oranges are in between their two parents in size, flavor, and shape. Both the bitter orange and sweet orange came from mandarin-pomelo mixes.

- Grapefruit: Grapefruits also have genes from both mandarin and pomelo. But they have more pomelo genes. They came from a natural mix of a sweet orange and a pomelo.

- Lemon: "True" lemons come from one common hybrid ancestor. The original lemon was a mix of a male citron and a female sour orange (which was itself a pomelo/pure-mandarin hybrid). Citrons contribute half of the lemon's genes, while the other half comes from pomelo and mandarin. There are other hybrids also called 'lemons'. Rough lemons are a mix of citron and mandarin, without the pomelo part. The Meyer lemon is a mix of a citron and a sweet orange.

- Limes: Many different hybrids are called 'limes'. Rangpur limes, like rough lemons, are mixes of citron and mandarin. The sweet limes (which have low acid) come from mixes of citron with either sweet or sour oranges. The Key lime came from a mix of a citron and a micrantha.

All these hybrids have been mixed again with their parent types or other citrus to create even more fruits. Their names can be confusing. For example, the Ponderosa lemon and Florentine citron are both lemon/citron hybrids. The Bergamot orange is a sweet orange/lemon hybrid. The Oroblanco is a grapefruit/pomelo mix. Tangelos are tangerine/pomelo or mandarin/grapefruit hybrids. Orangelos are grapefruit mixed back with sweet orange. A sweet orange mixed back with a tangerine gives the tangor.

One type of lumia is a mix of a lemon and a pomelo/citron hybrid. Another lumia, the Pomme d'Adam, is a micrantha/citron mix, like the Key lime. The most common commercial 'limes', the Persian limes, are Key lime/lemon hybrids. This means they have genes from four ancestral citrus species: mandarin, pomelo, citron, and micrantha.

Most citrus plants have two sets of chromosomes (diploid). But many Key lime hybrids have unusual numbers of chromosomes. For example, the Persian lime has three sets of chromosomes (triploid). This comes from a Key lime egg cell with two sets of chromosomes and a lemon sperm cell with one set. The "Giant Key lime" is bigger because it has four sets of chromosomes (tetraploid).

Historically, hybrids that looked similar were grouped together. But recent genetic studies show that some hybrids in the same group have very different family histories. No new system for grouping these hybrids has been widely accepted yet.

Hybrids from Other Citrus Species

While most citrus hybrids come from the three core species, hybrids have also been made from the micrantha, Ichang papeda, kumquat, Australian limes, and trifoliate orange. The most famous hybrid from micrantha is the Key lime (or Mexican lime). It came from a male citron and a female micrantha.

Several citrus varieties are mixes of Ichang papeda and mandarin. These include Sudachi and Yuzu (which also has small amounts of pomelo and kumquat). Other unusual citrus fruits have also been found to be hybrids that include papeda. For example, the Indian wild orange was once thought to be an ancestor of today's citrus. But genetic studies show it's a hybrid with genes from citron, mandarin, and papeda.

Citrofortunella (Kumquat Hybrids)

A large group of commercial hybrids involve the kumquat. In the old Swingle system, a special group called Citrofortunella was made for mixes between Citrus and Fortunella (kumquats). These hybrids often combine the kumquat's cold hardiness with some edible qualities of other citrus. These crosses were marked with a multiplication sign (×) before the name, like × Citrofortunella microcarpa.

Now that kumquats are considered part of the Citrus genus, Citrofortunella is no longer a separate group. These hybrids are now just part of the Citrus genus. Examples of these hybrids include the calamansi (kumquat and tangerine mix), limequat (kumquat and Key lime mix), and yuzuquat (kumquat and yuzu mix).

Citroncirus (Trifoliate Orange Hybrids)

Like kumquats, the trifoliate orange doesn't naturally mix with core citrus types because they flower at different times. But hybrids have been made artificially between Poncirus (trifoliate orange) and members of the Citrus genus. In the Swingle system, the name for these mixes was "× Citroncirus". This group includes the citrange (a mix of trifoliate and sweet orange) and the citrumelo (a mix of trifoliate orange and 'Duncan' grapefruit).

If Poncirus is included in Citrus, then Citroncirus would also no longer be a separate group.

Graft Hybrids: Two Plants in One

Many farmed citrus trees are grown by grafting. This means joining a cutting (the scion) from one plant onto the root system (the rootstock) of another. This is done because many genetic hybrids can't reproduce well, or because some citrus trees are sensitive to diseases or temperature. The rootstock is often a hardier, but less tasty, citrus type.

Sometimes, a special kind of hybrid called a graft hybrid (or graft-chimaera) can happen. This is not a genetic mix. Instead, cells from the scion and rootstock mix together at the graft site. This can lead to branches on the same tree that produce different fruits! For example, the 'Faris' lemon has some branches with purple leaves and sour fruit, while other branches have white flowers and sweet lemons.

Graft hybrids can also produce fruit that is a mix of both plants. In an extreme example, the Bizzaria tree produces fruit that looks like each of its two parent species on separate branches. But it also produces fruit that looks like half one species and half the other, all on the same fruit! In naming, graft hybrids are shown with a plus sign between the names of the two contributing species (e.g., Citrus medica + C. aurantium).

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |