Muhammad VIII al-Amin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Muhammad VIII al-amin |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lamine Bey | |||||

|

|||||

| King of Tunisia | |||||

| Reign | 20 March 1956 – 25 July 1957 | ||||

| Predecessor | Himself as Bey of Tunis | ||||

| Successor | (Habib Bourguiba as President of Tunisia) | ||||

| Bey of Tunis | |||||

| Reign | 15 May 1943 – 20 March 1956 | ||||

| Predecessor | Muhammad VII | ||||

| Successor | Position abolished (Himself as King of Tunisia) |

||||

| Born | September 4, 1881 Carthage, French Tunisia |

||||

| Died | September 30, 1962 (aged 81) Tunis, Tunisia |

||||

| Burial | Cemetery of Sidi Abdulaziz, La Marsa | ||||

| Spouse |

Lalla Jeneïna Beya

(m. 1902; died 1960) |

||||

|

|||||

| Name in Arabic | الأمين باي بن محمد الحبيب | ||||

| Dynasty | Husainid Dynasty | ||||

| Father | Muhammad VI al-Habib | ||||

| Mother | Lalla Fatouma El-Ismaila | ||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||

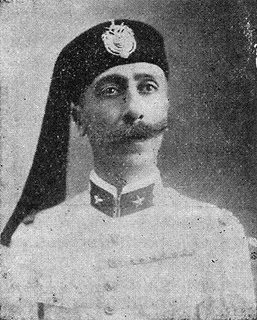

Muhammad VIII al-Amin (Arabic: محمد الثامن الأمين; born September 4, 1881 – died September 30, 1962), often known as Lamine Bey (Arabic: الأمين باي), was an important ruler in Tunisia's history. He was the last Bey of Tunis, ruling from 1943 to 1956. He also became the only King of Tunisia for a short time, from 1956 to 1957.

Lamine Bey became ruler during a difficult period. His predecessor, Muhammad VII al-Munsif, was removed from power by the French in 1943. At first, many Tunisians did not see Lamine Bey as the rightful ruler. However, after Muhammad VII passed away in 1948, Lamine Bey's position became more accepted. He tried to support the Tunisian national movement that wanted independence from France. But later, he was set aside by the Neo Destour party after accepting some French changes. After Tunisia gained independence, Lamine Bey and his family were removed from their palace. Their belongings were taken, and some family members were put in prison. He spent his final years living in a small apartment in Tunis.

Contents

Becoming Crown Prince

On June 19, 1942, Ahmed II passed away. He was followed by Muhammad VII al-Munsif, also known as Moncef Bey. Following tradition, on June 25, Moncef Bey named Lamine Bey as the Bey al-Mahalla, which means the heir apparent or Crown Prince. This made Lamine Bey the next in line to rule.

Lamine Bey showed his loyalty to Moncef Bey soon after. A court advisor tried to convince the French official to remove Moncef Bey from power. However, Lamine Bey warned the ruler about this plan. Because of this, the advisor was removed from the palace.

Taking the Throne

In May 1943, during the end of the Tunisian Campaign, a French general arrived in Tunis. He had orders to remove Muhammad VII from power. This was because Muhammad VII was accused of working with certain groups during the war. The general tried to get Moncef Bey to step down, but he refused.

The general then visited Lamine Bey to see if he would accept the throne. At first, Lamine Bey was unsure. But he eventually agreed, partly because it would help his family. Since Moncef Bey would not step down, the French general removed him on May 14, 1943.

Muhammad VIII was officially made ruler on May 15, 1943, at the Bardo palace. He received honors from other princes, ministers, and officials. He also brought back the tradition of kissing the ruler's hand, which his predecessor had stopped. On the same day, a new government was formed. Under French rule, the Bey usually did not choose his ministers. It was only on July 6 that Moncef Bey officially stepped down. This made Lamine Bey's rule legitimate. However, many Tunisians still saw him as someone who took power unfairly.

Early Years as Ruler (1943–1948)

Lamine Bey faced challenges in his early rule. Many people wanted Moncef Bey to return. When Lamine Bey appeared in public, his subjects often seemed uninterested or even unfriendly. To gain more support, he backed striking teachers and chose nationalist politicians as ministers. Despite this, rumors spread that he wanted to give the throne back to Moncef Bey. When these rumors were denied, his popularity dropped again.

In May 1944, Charles de Gaulle, a French leader, visited Tunis. Tunisians hoped he would bring Moncef Bey back. But this did not happen. Instead, De Gaulle gave Lamine Bey a special medal. This was because Lamine Bey had secretly listened to De Gaulle's radio broadcasts during the war.

People's dislike for Lamine Bey continued. Other princes of his family avoided him at a religious festival. To improve his image, he was invited to Paris and Germany. But for many Tunisians, he was still seen as "The Bey of the French." His health suffered because of this widespread dislike.

In 1947, a new French official arrived in Tunis. The political situation was still tense. Nationalist groups wanted Lamine Bey removed and Moncef Bey brought back. The French government refused to restore Moncef Bey. A new chief minister was appointed, and for the first time, there were equal numbers of Tunisians and French in the government.

Moncef Bey passed away in exile on September 1, 1948. His body was brought back to Tunis for burial, and thousands of Tunisians came to pay their respects. Moncef Bey's family even threatened to boycott the ceremony if Lamine Bey attended. However, this event marked a turning point for Lamine Bey. With Moncef Bey gone, people began to see Lamine Bey as their rightful ruler for the first time.

Working with Nationalists (1948–1953)

After Moncef Bey's death, Lamine Bey's relationship with the nationalists improved. He secretly worked with leaders like Habib Bourguiba to push for Tunisia's self-government. This put a lot of pressure on the French authorities between 1948 and 1951.

In 1952, a new French official took office. He was much tougher and had Bourguiba and other nationalist leaders arrested. Lamine Bey sent an angry message to the French President, complaining about the official's rude behavior. However, this only led to all of Lamine Bey's ministers being arrested. Without his ministers, Lamine Bey eventually had to sign a paper naming a new chief minister chosen by the French. But he refused to sign any other new laws, which stopped the government from working.

With his advisors in prison, Lamine Bey relied on the help of a trade union leader named Farhat Hached. Sadly, in December 1952, Hached was tragically killed by a group of French settlers. Unable to resist the French official any longer, Lamine Bey eventually signed decrees for limited self-rule. However, these changes did not work well. Nationalists started a campaign against those who participated in the new elections. This even affected the ruling family. In July 1953, Lamine Bey's heir, Azzedine Bey, was killed inside his palace. He was accused of having secret talks with the French official.

In September 1953, the tough French official was replaced. The new official took a more friendly approach. Thousands of prisoners were freed, and censorship was reduced. However, the French government still wanted to work only with the Bey, not with the nationalist party. They hoped to create a division between the ruler and the nationalists. Lamine Bey was smart enough not to be fooled. He refused to attend an important event because some harsh measures were still in place. More efforts were made to please him, and some nationalist leaders were freed and met by the Bey. But Bourguiba, seen as very dangerous by France, remained imprisoned.

Shifting Power and Independence (1953–1956)

With Bourguiba still in exile, Lamine Bey asked Mohamed Salah Mzali to discuss new reforms with the French official. By January 1954, enough progress was made that the Bey asked Mzali to form a new government. Some nationalists were willing to try these reforms. However, the French refusal to free Bourguiba remained a major problem for many Tunisians, including Bourguiba himself. Bourguiba felt that his release was being delayed. In May, Bourguiba, who had been moved to France, returned a special medal he had received from the Bey.

Mzali's government resigned in June 1954, and no one was appointed to replace it. The Bey was upset that his efforts had failed. He told the French official that he had only received threats when asking for Bourguiba's release. He even said he was ready to fight to reconnect with his people, feeling that the French had tried to separate him from them.

On July 31, 1954, the new French Prime Minister arrived in Tunis. He met Lamine Bey and announced that Tunisia would gain internal self-rule. This was a pleasant surprise for the Bey, who had not been part of the discussions before the visit. Soon after, the Bey spoke to his people. He said that a new phase had begun for Tunisia and that everyone must work together peacefully for progress. However, it was clear that power was moving away from the Bey. The French now saw the nationalist party as the main group to talk to.

Despite the Bey's efforts, a new government was formed without consulting him. To try and regain some influence, he suggested to the French government that his role as Bey should become a full monarchy. This would give him more authority. He was willing to sign agreements to keep French-Tunisian cooperation. He also contacted a nationalist leader in exile. None of these attempts worked.

After six months of talks, the self-rule agreements were signed on June 3, 1955. Bourguiba returned to Tunis on June 1, welcomed by the Bey's sons and a huge crowd. Bourguiba visited the Bey and spoke about the Tunisian people's strong support for the Bey's rule. On August 7, the Bey approved the agreements with France. On September 1, for the first time since 1881, he approved laws that had not been authorized by the French official. On December 29, 1955, he approved a law to create a special assembly for the country, with elections to be held in April 1956. Tunisia seemed to be moving towards becoming a constitutional monarchy, where the ruler shares power with a government.

However, as independence got closer, Lamine Bey's power continued to decrease quickly. Another nationalist leader returned from exile in September 1955. The Bey hoped this would help restore his political power. But violence soon broke out between followers of this leader and Bourguiba's supporters. The Bey tried to calm things down, but he had little power. The French had already given control of the police to the Tunisian government, which was chosen by Bourguiba.

In December, the Bey called the French official to remind him of France's responsibility for public order. But France no longer had this control. The Bey was asking for colonial powers to be restored against the nationalist government. Since his requests had no effect, he used his last remaining power. He refused to approve the laws for the upcoming elections and the appointment of local leaders. This move was supported by the other nationalist leader, but it made Bourguiba and his followers even more angry. The Bey backed down and signed the laws the next day. The other nationalist leader fled the country, and his supporters in Tunisia were cracked down on. Horrified by this, Lamine Bey protested again to the French official in April 1956. This only made Bourguiba furious. He went to the palace and accused the Bey and his family of trying to stop the transfer of power from France to the Tunisian government. On March 20, 1956, the agreement for Tunisia's independence was signed.

From King to Citizen (1956–1957)

The French protectorate in Tunisia officially ended on March 20, 1956. On the same day, Tunisia was declared a kingdom, and the Bey became the King of Tunisia. However, his time as king was very short.

The elections for the new assembly in 1956 resulted in a huge win for the National Union, an alliance of nationalist groups. They won all 98 seats. After the election, King Muhammad VIII removed the Prime Minister and appointed Bourguiba as the new head of government.

The new assembly held its first meeting on April 8, 1956. It was a sign of the changing times that the King wore an old military uniform from the Ottoman Empire, which no longer existed. He expected to stay for the debates, but he was asked to leave. The King left, clearly unhappy.

On May 31, a law from the assembly removed all special rights and benefits that the ruling family had. They were now just ordinary citizens. This meant the King's family no longer received payments, and the royal properties came under government control. The King signed this law without protest. Other laws followed, changing national symbols to remove any reference to his family. Another law, on August 31, took away the King's power to make rules, giving this power to the Prime Minister.

More laws forced the King to give various properties to the state. There were also negative news reports questioning how some properties were obtained. These actions greatly reduced the King's remaining importance. Still, King Muhammad VIII was the first person to receive the new Order of Independence medal in December 1956. He, in turn, gave Bourguiba a special medal. However, Bourguiba clearly had little respect left for the ruling family. In July, during a religious festival, he visited the King's wife but refused to approach the throne. He stated he was there as head of government and expected the King's wife to come to him.

On July 15, 1957, the Tunisian army replaced the Royal Guard around the palace. After this, the King could not move freely. On July 18, his younger son was arrested based on untrue charges.

On July 25, 1957, the assembly voted to end the monarchy, declare Tunisia a Republic, and make Bourguiba President.

Immediately, a group of officials went to the palace to inform the King of the decision. They asked him to leave the palace with his wife, their three sons, seven daughters, and grandchildren.

Later Life and Legacy

The 75-year-old Muhammad left his palace wearing simple clothes. He was taken to an old, abandoned palace without water or electricity. This palace was assigned to him and several family members. Their new home had only a mattress on the floor, with no sheets. Food was provided for the first three days, and then the family had to find their own.

Some of his sons were later moved to prison. The old couple was not allowed to leave the ruined palace until October 1958, as Lamine's health had become very poor. They were then moved to a small villa with basic facilities and given a small monthly allowance. They remained under house arrest and were not allowed to go into the garden. A policeman was even on duty inside the villa. However, their daughter was allowed to visit them.

Two years later, the search for some jewels that had belonged to the Bey's wife was renewed. Both the former King and his wife were called for questioning. Lamine's wife was questioned for a long time, which made her very ill. She passed away two days later. She was buried in a cemetery in La Marsa, with her sons present. Lamine was not allowed to leave his villa for the burial. The public was also kept away by the police.

Several days later, the former King's house arrest was lifted. Lamine was allowed to go into his garden and visit his wife's tomb. He moved into an apartment in Tunis. When his son Chedly was freed in 1961, he joined them in a small apartment that was constantly watched.

Muhammad passed away on September 30, 1962, at the age of 81. He was buried next to his wife. This was different from most rulers of his family, who were buried in a special mausoleum in Tunis. A single photographer recorded the event and was briefly detained by the police for doing so. His son, Husain Bey, became the head of the Husainid Dynasty after him.

His Family

Lamine Bey married Lalla Jeneïna Beya (1887–1960) in 1902. She was the daughter of a merchant from Tunis. They had twelve children together: three sons and nine daughters.

- Princess Lalla Aïcha (1906–1994): She was the eldest daughter and sometimes represented her father. She welcomed Habib Bourguiba when he returned to Tunisia in 1955. She married Slaheddine Meherzi and had three sons.

- Princess Lalla Khadija (1909–199?): She married Khaireddine Azzouz in 1939.

- Prince Chedly Bey (1910–2004): He was the director of the Royal Cabinet from 1950 to 1957. He also became the head of the Royal Family from 2001 to 2004. He married princess Hosn El Oujoud Zakkaria.

- Princess Lalla Soufia (1912–1994): She married Prince Mohamed Hédi Bey, then later Hédi Ben Mustapha, and then Ahmed Kassar.

- Prince Mohammed Bey (1914–1999): He married Safiya, who was raised by Lalla Kmar, a wife of previous rulers. They had four sons and one daughter.

- Prince Salaheddine Bey (1919–2003): He founded a sports club called CS Hammam-Lif. He was arrested in August 1957 after the monarchy was ended. He married Habiba Meherzi and later Liliane Zid. He had children from both marriages.

- Princess Lalla Zeneïkha Zanoukha (1923–2007): She married Colonel Nasreddine Zakaria in 1944. They had two sons and three daughters.

- Princess Lalla Fatma (1924–1957): She was the wife of Mustapha Ben Abdallah, a deputy Governor. They had two sons and one daughter.

- Princess Lalla Kabira Kabboura (1926–2007): She was the wife of Mohamed Aziz Bahri, the chief of protocol. They had four sons and two daughters.

- Princess Lalla Zakia Zakoua (1927–1998): She married Mohamed Ben Salem in 1944, who later became a minister of health. They had three sons and three daughters.

- Princess Lalla Lilia (1929–2021): She married Dr Menchari, then Hamadi Chelli. She chose to live in Morocco after the monarchy was abolished in 1957. She returned to Tunisia later. She had two sons and one daughter.

- Princess Lalla Hédia (1931–2010): She married the engineer Osman Bahri. They had two sons and three daughters.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Muhammad VIII al-Amin para niños

In Spanish: Muhammad VIII al-Amin para niños