New York Free Circulating Library facts for kids

Quick facts for kids New York Free Circulating Library |

|

|---|---|

|

|

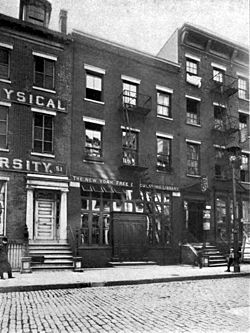

| 49 Bond Street (opened 1883) where the first branch of the NYFCL settled for most of its existence. | |

| Country | United States |

| Type | Public lending library |

| Established | 1879 |

| Location | New York, New York |

| Branches | 11 |

| Access and use | |

| Circulation | 1,600,000 (1900) |

The New York Free Circulating Library (NYFCL) started in 1879. Its main goal was to give free books and reading spaces to people in New York City. It grew from one spot to eleven different locations. It also had a special traveling book service. Many women helped run the library and worked there. In 1901, this library system joined the larger New York Public Library.

Contents

How It Started

In the 1870s and 1880s, many people in New York City felt there weren't enough free books for everyone. Newspapers and government talks often mentioned this need. People really wanted a good way to borrow books for free.

One day in early 1879, six girls were waiting for their sewing class at Grace Church. To pass the time, one girl read a thrilling story from a cheap paper. Their teacher arrived and heard the story. She asked about the children's reading habits.

The teacher wanted to help them find better books. The girls happily traded the paper for a book. Each girl was offered one free book a week. The only rule was they couldn't buy those sensational story papers anymore.

Other women became interested in this idea. Soon, they collected about 500 books. They found a room on 13th Street to use as a library. They told the children to bring their friends.

At first, the room was open only once a week for two hours. But so many people came that the sidewalk got crowded! One time, almost all the books were borrowed. Only two were left in the room.

By the end of the first year, the library had about 1,200 books. All of these books were gifts. About 7,000 books had been borrowed by the public. People of all ages, from children to older adults, used the library. They came from all over the city.

After looking at other libraries, everyone agreed. New York City really needed a library. It needed a place where even very poor people could borrow books for free.

Becoming an Official Library

To make the library official, a special document was filed in March 1880. This document made the library a legal organization. The people who started it included Benjamin H. Field and Mary S. Kernochan.

Their goal was to offer "free reading to the people of the City of New York." They wanted to do this by setting up libraries and reading rooms. These places would be open to everyone without any cost.

The library moved from 13th Street to 36 Bond Street. They rented two rooms in a private house. These rooms were set up as a library. Books started being borrowed from this new spot on March 22, 1880. They had 1,837 books on the shelves.

In April, the first full month, people borrowed 1,653 books. This number grew steadily. By October, 4,212 books were borrowed. On March 22, 712 people had library cards. By November 1, this number reached 2,751.

Most of the books borrowed were fiction or children's books (71%). History, biography, and travel books made up 18%. Other types included foreign books, science, poetry, and essays. On average, about 200 books were borrowed each day.

The number of books grew from 1,837 to 3,674. Some were bought, but most were gifts. However, many of the gifted books were not very useful. The library committee realized they needed better books. They wanted "standard works of fiction" and "popular books of travel and history." Most importantly, they wanted "the better class of books for boys and girls."

A reading room opened on June 1. It was open from 4 to 9 p.m., even on Sundays. Many people used it. Nearly 2,000 readers used 2,361 magazines and newspapers. The library also created a card catalog to help people find books.

In 1881, a library expert named Charles A. Cutter praised the library. He said it was a very important step for New York City. He hoped the library would grow beyond what was "suitable to a small country town."

Once the library was set up, its growth depended on having more books. And having more books depended on having more money. The library worked hard to get more funds and improve how it was run.

They held public meetings to ask for donations. On January 20, 1882, about 350 people attended a meeting. Mayor William R. Grace was there. Important speakers like Joseph H. Choate also gave speeches.

Famous lecturer Edward A. Freeman gave a series of talks to raise money. By November 1882, the library had raised about $34,000. This money helped them buy a building at 49 Bond Street on June 9, 1882. They spent $15,500 on the land and $13,774.92 to fix up the building.

The books moved from the rented rooms to the new building on May 1, 1883. Readers and librarians were very happy about the move. The number of books borrowed grew from 69,280 in its first full year to 81,233 in 1882-83.

Women played a big part in starting and running the library. In 1882, the Female Christian Home gave the library $2,000. They asked for this money to be called the "Women's Fund." The money was to be used to hire women or buy books for the library.

More Branches and Growth

The first library rules limited how much the library could grow. To fix this, a new law was passed in Albany on April 18, 1884. This law gave the library more freedom.

Soon after, on May 12, 1884, Oswald Ottendorfer sent a letter. He was the editor of a German newspaper. Ottendorfer wanted to give the NYFCL a new branch library. It would be at 135 2nd Avenue.

This new branch would have about 8,000 books. Half of them would be in German, and half in English. The German Hospital would lease the space to the library. Ottendorfer also gave $10,000 and furniture for the branch. It would include a reading room.

A condition of the gift was that the library always keep enough German books. It also needed German-speaking staff. The branch also had a fireproof vault. This vault was for important documents and books.

The library accepted this generous gift on May 16, 1884. At that time, Lower 2nd Avenue was home to many German-speaking people. The new branch was named the Ottendorfer Branch. It opened on December 8, 1884. It had 8,819 books, with 4,035 in German and 4,784 in English.

Getting Money

The NYFCL was now a proven success. Everyone could see how much it was needed. The library had a good system for providing books. Its only limit was money.

Eventually, the library started getting money from taxpayers. But until then, it relied on donations from wealthy people. These people often didn't know much about the library's work. But once they learned, they usually kept donating every year.

Meetings were held to explain the library's needs. Important community leaders spoke at these events. For example, in 1885, Andrew Carnegie spoke at a meeting. In 1886, Levi P. Morton led a meeting at Steinway Hall. Many other famous people, like ex-President Cleveland and Seth Low, also spoke at events.

The library also sent personal letters to people in different jobs. They explained the library's work and asked for support. In 1886, they sent letters to stock exchange members and railroad workers. In 1897, they sent out 5,000 such letters.

The first public funding came on July 15, 1886. A law was passed allowing cities to help free libraries. New York City started giving money to the NYFCL. This money was based on how many books were borrowed. From 1887 to 1900, the city gave the library $417,250. For several years, the city's money was much more than private donations.

Types of Books

The library committee always cared about the quality of the books. In 1886-87, they said they wanted to "improve the character of the reading." They avoided buying many short-lived or unimportant books. They also didn't buy too many copies of fiction books that might only be popular for a short time.

More Branches Open

For almost three years, the Bond Street and Ottendorfer Branches were the only ones. In 1888, the number of branches doubled. The George Bruce Branch and the Jackson Square Branch opened.

On January 17, 1887, Catherine W. Bruce gave $50,000. This money was for building and supporting a new branch. It was named the George Bruce Branch. It was built at 226 West 42nd Street. This branch was a memorial to her father, George Bruce. Catherine Bruce also gave more money to help this branch. It opened on January 6, 1888, with about 7,000 books.

The Jackson Square Branch opened on July 6, 1888. It was at 251 West 13th Street. The land, building, and books were a gift from George W. Vanderbilt.

The fifth branch, called Harlem Branch, started small. It opened on July 7, 1892. It was a small book distribution spot at 2059 Lexington Avenue. It got 500-600 books from the Bond Street and Jackson Square Branches. Over time, the Harlem Branch moved several times. Its final location was 218 East 125th Street in May 1899.

The sixth branch opened on February 25, 1893. It was in the Church of the Holy Communion. It was named the Muhlenberg Branch. This was in memory of the church's first leader, William Augustus Muhlenberg.

The seventh branch, Bloomingdale Branch, also got help from a church. It opened on June 3, 1896, at 816 Amsterdam Avenue. In 1898, the Bloomingdale Branch moved into the first building built with NYFCL's own money.

In 1897, two new branches opened. A third service, the Traveling Library department, also started. The Riverside Branch opened on May 26, 1897, at 261 West 69th Street. It used books from the Riverside Association. This was the first branch to let people pick books directly from the shelves.

The Yorkville Branch opened on June 10, 1897. It was at 1523 Second Avenue. This area had many Germans and Bohemians. They were a large part of the non-English readers. The branch was so busy that librarians from other branches helped out.

The idea of a traveling library started early. The NYFCL would send books to clubs, schools, or other groups. By 1897, this work was so big it needed its own department. It started at the George Bruce Branch. In 1898, it got its own staff and moved to the Ottendorfer Branch. In 1899, it moved to the Bloomingdale Branch.

The tenth branch opened on June 6, 1898. It was in a rented, remodeled house at 215 East 34th Street. The main borrowing room was on the first floor. The reading room was on the second. It opened with 3,710 books. In its first five months, 26,645 books were borrowed. About three-fourths of the readers were children.

Children used the library so much that special rooms were set aside for them. This idea was a big success. Soon, other branches got separate children's rooms. These included Ottendorfer, Bloomingdale, the new Harlem building, and the new Chatham Square Branch.

The last branch opened on July 5, 1899. It was at 22 East Broadway. It was in a remodeled house near Chatham Square, which gave it its name. The main borrowing room was on the first floor. The children's room was on the second. Each had about 3,000 books when it opened. But in the first four months, children borrowed 37,914 books out of 46,339 total.

Susan Travers gave $1,000 for books for the children's room at Chatham Square. She did this in memory of her friend Emily E. Binsse. She also gave six interesting sculptures.

As more branches opened, book borrowing grew a lot. From 69,000 books in its first year, it reached 1,600,000 books borrowed each year. This was across the eleven branches two decades later.

Library Staff

Women played a very important role in the NYFCL. The first president, secretary, and head of the building committee were all women. The first librarian was also a woman. Out of 40 trustees from 1880 to 1901, 19 were women. Almost all the working staff were women.

In March 1897, the staff was put into different levels. There were four classes: A, B, C, and D. Class A was for librarians in charge of branches. To move up to a higher level, staff had to pass exams and show good work.

To train new helpers, an apprentice class started in February 1898. People who wanted to work at the library had to fill out a form. They shared their past training and education. They promised to work 45 hours a week. In return, they got special training.

After some initial training, apprentices worked at different branches. This helped them learn about local needs. It also gave librarians a chance to see their work. When a paid helper was needed, they chose from the apprentice class. The best-suited apprentice got a permanent job. Sometimes, someone showed they were a good fit in just two weeks. Other times, it took months of service.

The NYFCL had four chief librarians during its 21 years. The first librarian was Mary J. Stubbs. She lived in the library building from 1880 to 1881. She left due to illness and later passed away. Her sister took over for a short time.

In late 1881, Ellen M. Coe became the chief librarian. She held the job for about 14 years. Under her leadership, five new branches opened. The number of books borrowed grew from 69,000 to 650,000.

On April 1, 1895, Arthur E. Bostwick became chief librarian. He left in March 1899. His replacement, J. Norris Wing, started in April. Wing died in December 1900. The position stayed empty until the NYFCL joined the New York Public Library.

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |