Obed Dickinson facts for kids

Obed Dickinson (born June 15, 1818 – died November 27, 1892) was an important American pioneer, minister, and business owner. He was also a strong supporter of ending slavery. Born in Massachusetts, he later moved to Salem, Oregon. There, he served as a minister and started a successful seed business.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Obed Dickinson was born in Amherst, Massachusetts, on June 15, 1818. He was the oldest son of Obed Sr. and Experience Smith. In 1836, his father moved to Michigan and bought a large amount of land. Obed's mother and siblings joined him later.

Two years later, Obed Sr. died. Young Obed Jr. then took care of his family and worked on their farm. He stayed on the farm until he was 25 years old. Then, he left to attend Marietta College in Ohio.

After finishing college in 1849, he went to Andover Theological Seminary. He was given permission to preach by the Andover Association. In 1852, he officially became a Congregational missionary. Missionaries are people who travel to spread their religious beliefs.

Moving to Oregon

Obed Dickinson married Charlotte Dryer Humphrey on September 22, 1852. He was 34 and she was 35. In November of that year, they sailed from New York on a ship called Trade Wind. They were heading for the Oregon Territory.

Charlotte kept a detailed diary of their journey. The trip took four months and sailed around the very tip of Cape Horn in South America. About 50 passengers were on board, including several children.

Obed and Charlotte arrived in Portland, Oregon in April 1853. It was decided that Dickinson would serve as a minister in Salem. Salem was chosen because it was the capital and a growing area. The town was also home to a Methodist church university.

It took 18 days for Obed and Charlotte to travel from Portland to Salem. They traveled by boat and horse-drawn cart. They brought their furniture, bedding, and other personal items. When they arrived, the Congregational church in Salem had only four members. The town's population was about 500 people.

In Salem, they bought a small piece of land and built a small home. They did not have much money. Obed often wrote to the American Home Missionary Society asking for help. He once wrote, "I am now so much in debt that I almost feel ashamed to meet a man in the street."

Fighting for Equality

Obed Dickinson and his wife were abolitionists. This means they strongly believed in ending slavery. Congregational ministers often spoke out against slavery. They called it morally wrong in their meetings.

However, most ministers thought slavery should end slowly. Abolitionists like Dickinson believed slavery was a sin and must be stopped immediately. They also worked to challenge racial prejudice.

Dickinson showed his commitment to racial equality in many ways. In 1863, he said, "It is true, we have no slavery now in Oregon, but we have that which is equally wrong: a prejudice and a hatred to the oppressed race."

On March 3, 1861, Dickinson welcomed nine new members to the Salem church. Three of these new members were African American. They were the first Black members of a Congregational church in Oregon. They might have been the first Black members of any "white" church in the state.

That same year, Dickinson preached a sermon about Christian equality. He spoke about the problems of social class and racial differences. The mixed-race members of his church and his sermons upset some people. The local newspaper, the Statesman, wrote negative articles.

The church's main donor, Deacon Isaac Newton Gilbert, stopped giving money. He usually gave $100 each year. Dickinson wrote to the Missionary Society about this. He said the deacon would not pay "as long as I did and preached, in the way I did."

In the same letter, Dickinson explained what he preached. He said, "I said there is a wrong public opinion in this town. It has closed the doors of all our schools against the children of these black families dooming them to ignorance for life. I said it was wrong to take away the key of knowledge from any human."

In December 1861, the Mission Society sent Dickinson a letter. They warned him that if his church did not get more money, they might stop supporting him.

In July 1862, Dickinson wrote to the Missionary Society again. He updated them on his church and his abolitionist work. He noted that Black children were still not allowed in public schools. But his wife, Charlotte, was teaching them. She taught a group of four or five children every evening.

In early 1863, there were many meetings in the Salem church about Dickinson's views. Church members agreed with his anti-slavery ideas. But they questioned his strong way of speaking about them. The local Statesman newspaper learned of these disagreements. It published an article saying Dickinson was spreading "negro-equality sentiment." The article suggested Dickinson would soon leave the church.

The Portland Commercial Reporter newspaper also wrote about Dickinson. It suggested he should "go to Africa to preach." In March 1863, Dickinson was not chosen to lead the church again. Because he left, the church was able to raise money to build a new church building. After raising the funds, the church asked Dickinson to return in June. He came back in September of that year.

A Special Wedding

In Salem, on January 1, 1863, Dickinson led the wedding of America Waldo and Richard Arthur Bogle. Both America and Richard were Black residents of Salem. Dickinson also hosted their wedding reception.

The wedding happened on the same day that President Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation became law. This important document declared many enslaved people free. The wedding and reception were controversial. Both white and Black guests attended, which went against the racial segregation rules of that time.

The editor of the Oregon Statesman, Asahel Bush, called the wedding "shameful." He wrote that it was "negro equality sentiment mixed up with a little snob-aristocracy." His newspaper also said Dickinson's preaching was stopping the church from growing.

The Oregonian newspaper disagreed with Bush. It said that a man who would make fun of a "poor mulatto girl's feelings is blacker than the skin of any African." News of the wedding even reached the San Francisco Bulletin. It reported that "distinguished white ladies and gentlemen" attended the ceremony.

Leaving the Church

Even with pressure from his church and the newspapers, Dickinson never changed his beliefs. He continued to speak out against slavery and for racial equality. When Dickinson left the Congregational church in 1867, the church had 96 members. This was a big increase from the four members it had when he started in 1853. Dickinson left because of the pressure to stop speaking so strongly about equality.

Later Life and Business

The church did not pay Dickinson enough money to support his family. He wrote in his letters that he had to do the work of two men: a pastor and a laborer.

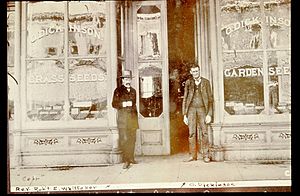

Dickinson started his seed business in 1865. He was still working as a minister for the Congregational church at that time. That year, he paid the Oregon Statesman to print 1,000 labels for his seeds. He also printed 800 leaflets listing his goods for sale. After he left the church in 1867, he focused on his seed business and nursery.

He also spent time helping his community. He was a director for public schools. He was also a trustee for Willamette and Pacific universities.

In 1876, he became a Seventh Day Adventist. He later became a pastor for that church. His seed business grew and continued even after his death in 1892.

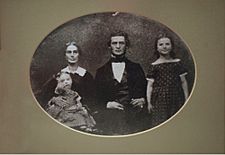

Family

Dickinson and his wife Charlotte had four children. However, only one, Cora Lamira, lived past infancy. They later adopted a second daughter named Edna.

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |