Okapi facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Okapi |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Male okapi at Beauval Zoo | |

|

|

| Female okapi at Zoo Miami | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Giraffidae |

| Genus: | Okapia Lankester, 1901 |

| Species: |

O. johnstoni

|

| Binomial name | |

| Okapia johnstoni (P.L. Sclater, 1901)

|

|

|

|

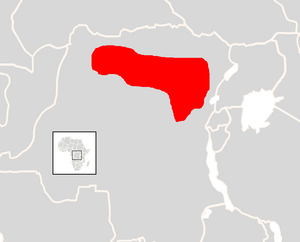

| Range of the okapi | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The okapi (pronounced oh-KAH-pee) is a unique animal. It is also called the forest giraffe or zebra giraffe. This mammal lives only in the northeast Democratic Republic of the Congo in central Africa. It is the only living species in its group, Okapia.

Even though okapis have stripes like zebras, they are actually related to giraffes. The okapi and the giraffe are the only two living animals in the Giraffidae family.

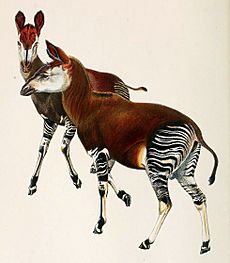

An okapi stands about 1.5 meters (5 feet) tall at the shoulder. Its body is about 2.5 meters (8 feet) long. Okapis weigh between 200 and 350 kilograms (440 to 770 pounds). They have a long neck and big, flexible ears. Their fur is a chocolate to reddish-brown color. This contrasts sharply with the white stripes and rings on their legs and white ankles.

Male okapis have short, horn-like bumps on their heads called ossicones. These are less than 15 centimeters (6 inches) long. Female okapis do not have ossicones. Instead, they have swirls of hair on their heads.

Okapis are mostly active during the day. But they might also be active for a few hours at night. They usually live alone, only meeting up to have babies. Okapis are herbivores, meaning they eat plants. They munch on tree leaves, buds, grasses, ferns, fruits, and even fungi.

Baby okapis are usually born after a long pregnancy of about 440 to 450 days. The young are kept hidden by their mothers. They start eating solid food around three months old. They stop drinking milk at six months.

Okapis live in thick forests between 500 and 1500 meters (1,600 to 4,900 feet) high. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) lists the okapi as an endangered species. This means they are at high risk of disappearing forever. Their homes are being lost because of logging and people building new settlements. Hunting for meat and skin, and illegal mining, also threaten them. The Okapi Conservation Project started in 1987 to help protect these amazing animals.

Contents

Discovering the Okapi

For a long time, people in the Western world did not know about the okapi. But it might have been shown in ancient art from the early 400s BCE. This was on a building in Persepolis, as a gift from Ethiopia.

Europeans in Africa heard stories about a mysterious animal. They called it the "African unicorn." In 1887, explorer Henry Morton Stanley wrote about a donkey-like animal. Locals called it the atti. Later, experts realized this was the okapi.

Sir Harry Johnston, a British official, became curious about this animal. He rescued some Pygmy people who had been taken away. He promised to return them home. The Pygmies told Johnston more about the animal. They showed him its tracks. Johnston was surprised because the tracks looked like a cloven-hoofed animal, not a horse.

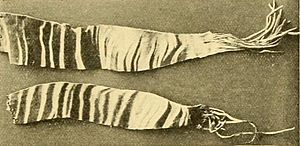

Sir Harry Johnston never saw a live okapi. But he did get pieces of its striped skin and later a skull. From the skull, scientists correctly figured out that the okapi was related to the giraffe. In 1901, the species was officially named Okapia johnstoni.

The name Okapia comes from local African languages. The name johnstoni honors Sir Harry Johnston. He was the first to get an okapi specimen for science from the Ituri Forest.

Okapi Features

The okapi is a medium-sized animal in the giraffe family. It stands about 1.5 meters (5 feet) tall at the shoulder. Its average body length is about 2.5 meters (8 feet). It weighs between 200 and 350 kilograms (440 to 770 pounds). It has a long neck and large, flexible ears.

The okapi's fur is a dark chocolate to reddish-brown. This color is a strong contrast to the white horizontal stripes on its legs and white ankles. These stripes look like a zebra's. They help the okapi hide well in the dense forest plants. Its face, throat, and chest are grayish-white.

Male okapis have short, hair-covered horn-like structures called ossicones. These are less than 15 centimeters (6 inches) long. Female okapis are usually a bit taller and redder. They do not have ossicones. Instead, they have swirls of hair.

Okapis have special features that help them live in their tropical forest home. They have many cells in their eyes that help them see well at night. They also have a very good sense of smell. Their large ear bones give them excellent hearing.

The okapi is easy to tell apart from its closest living relative, the giraffe. The okapi is much smaller. It looks more like cattle or deer. Only male okapis have ossicones, but both male and female giraffes have them.

Both okapis and giraffes walk in a special way. They move both the front and back leg on the same side of their body at the same time. Most other hoofed animals move opposite legs. They also both have long, black tongues. The okapi's tongue is even longer. It uses its tongue to grab leaves and buds, and also to clean its ears and eyes!

Okapi Behavior

Okapis are mostly active during the day. But they can also be active for a few hours in the dark. They are usually solitary animals, meaning they live alone. They only come together to breed.

Males often mark their areas and bushes with their urine. Females use shared spots to go to the bathroom. Okapis often rub their necks against trees. This leaves a brown liquid behind.

Male okapis protect their territory. But they let females pass through to find food. Males visit female areas when it's time to breed. Okapis are usually calm. But they can kick and butt with their heads if they feel threatened.

Okapis don't have very strong vocal cords. So, they mostly make three sounds. They "chuff" to call each other. Females "moan" during courtship. Babies "bleat" when they are scared. Okapis might also curl back their upper lips and show their teeth. This helps them smell things better. The main natural enemy of the okapi is the leopard.

Okapi Diet

Okapis are plant-eaters. They eat leaves and buds from trees, branches, grasses, ferns, fruits, and fungi. They are special in the Ituri Forest because they are the only known mammal that eats only plants from the lower parts of the forest. They use their 45-centimeter (18-inch) long tongues to pick out the right plants.

Okapis are known to eat over 100 different kinds of plants. Some of these plants are even poisonous to humans and other animals! But studies show that no single plant makes up most of their diet. They mostly eat shrubs and vines.

Okapi Reproduction and Life Cycle

Female okapis can start having babies when they are about one and a half years old. Males are ready to breed after two years. Okapis can breed at any time of the year. In zoos, females are ready to breed every 15 days.

The male and female start by circling, smelling, and licking each other. The male shows he is interested by stretching his neck, tossing his head, and moving one leg forward. Then they mate.

The mother okapi is pregnant for about 440 to 450 days. Usually, only one baby is born. The baby weighs between 14 and 30 kilograms (30 to 66 pounds). The mother eats the afterbirth and cleans her baby very carefully. Her milk is very rich in protein and low in fat.

Like other hoofed animals, the baby okapi can stand within 30 minutes of being born. Baby okapis look similar to adults. But they have long hairs around their eyes, a long mane on their back, and long white hairs in their stripes. These features slowly disappear within a year.

Mothers keep their babies hidden. They don't nurse them very often. Baby okapis are known not to poop for the first month or two of their lives. This might help them avoid being found by predators when they are most vulnerable. Babies grow very fast in their first few months. They start eating solid food at 3 months old. They stop drinking milk at 6 months. Male okapis grow their ossicones about one year after birth. Okapis usually live for 20 to 30 years.

Okapi Habitat

The okapi lives only in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It is found north and east of the Congo River. Its home stretches from Maiko National Park up to the Ituri rainforest. It also lives in the river areas of the Rubi, Lake Tele, and Ebola to the west, and the Ubangi River further north. Some smaller groups live west and south of the Congo River. Okapis are also common in the Wamba and Epulu areas. They are no longer found in Uganda.

Okapis live in thick forests at heights of 500 to 1500 meters (1,600 to 4,900 feet). They sometimes use areas that flood during certain seasons. But they do not live in swamp forests or places disturbed by people. During the wet season, they visit rocky hills that have food not found elsewhere.

Okapi Conservation Status

The IUCN lists the okapi as an endangered species. This means they are at high risk of disappearing. The okapi is fully protected by the laws of the Congo. The Okapi Wildlife Reserve and Maiko National Park are home to many okapis. But their numbers are still going down.

Threats to Okapis

The biggest threats to okapis include losing their homes. This happens because of logging (cutting down trees) and people building new settlements. A lot of hunting for bushmeat (wild animal meat) and skin, along with illegal mining, have also caused their numbers to drop.

A newer threat is the presence of illegal armed groups near protected areas. These groups make it hard for conservationists to protect and monitor the okapis. In June 2012, a group of poachers attacked the headquarters of the Okapi Wildlife Reserve. They killed six guards and other staff. They also killed all 14 okapis at the breeding center there.

Okapi Conservation Efforts

The Okapi Conservation Project started in 1987. It works to protect okapis and also helps the local Mbuti people. In November 2011, the White Oak Conservation center and Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens held a big meeting. Representatives from zoos in the US, Europe, and Japan attended. They discussed how to manage okapis in zoos and how to support okapi conservation in the wild. Many zoos around the world now have okapis.

Okapis in Zoos

About 100 okapis live in zoos that are approved by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA). The AZA's Species Survival Plan helps manage the okapi population in America. This program helps make sure there is enough genetic variety among the okapis in zoos. The European and Global studbooks (records of animals) are managed by Antwerp Zoo in Belgium. Antwerp Zoo was the first zoo to show an okapi in 1919. They have also been very successful at breeding them.

In 1937, the Bronx Zoo was the first in North America to get an okapi. They have had a very successful breeding program. Thirteen baby okapis were born there between 1991 and 2011. The San Diego Zoo has had okapis since 1956. Their first baby okapi was born in 1962. Since then, over 60 okapis have been born at the zoo and the nearby San Diego Zoo Safari Park. The most recent was Mosi, a male calf born on July 21, 2017. The Brookfield Zoo in Chicago has also helped a lot with the okapi population in zoos. They have had 28 okapi births since 1959.

Many other zoos in North America and Europe also have okapis. These zoos help educate people about okapis. They also support conservation efforts.

Intersting facts about the okapi

- Although the okapi was unknown to the Western world until the 20th century, it may have been depicted since the early fifth century BCE on the façade of the Apadana at Persepolis, a gift from the Ethiopian procession to the Achaemenid kingdom.

- Baby Okapis don't usually poop for the first month or two, which scientists think helps keep their hiding spot from being discovered by predators.

- The okapi's typical lifespan is 20–30 years.

- The IUCN classifies the okapi as endangered.

- In 1937, the Bronx Zoo became the first in North America to acquire an okapi.

- In 2016, a genetic study found that the common ancestor of giraffe and okapi lived about 11.5 million years ago.

See also

In Spanish: Okapi para niños

In Spanish: Okapi para niños