Ecuadorian hillstar facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Ecuadorian hillstar |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Male on Chuquiraga sp. | |

|

|

| Female in Cotopaxi National Park | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Genus: |

Oreotrochilus

|

| Species: |

chimborazo

|

|

|

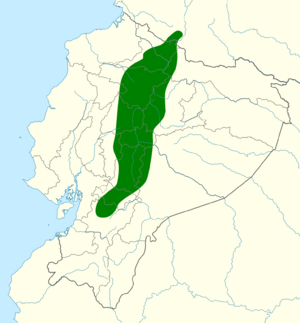

| Distribution (green) in Ecuador and South America | |

The Ecuadorian hillstar or Chimborazo hillstar (Oreotrochilus chimborazo) is a species of hummingbird. It is native to the Andes of Ecuador and extreme southern Colombia. Its main habitat type is high-altitude mountain grassland between 3500 and 5200 meters.

Description and range

The length of this species is about 12 cm, and it weighs approximately 8.0 g. It has a black bill that is slightly decurved and is about 2 cm long. The male has a glittering violet purple hood bordered below by a horizontal black chest stripe. It is dark olive green above and white below with a dark line down the center of the belly. The central tail feathers are blue-green and the rest are mostly white with black tips and edges. Females are duller dusty olive green above with a whitish throat speckled with brown spots. Its tail is dark and the rest of its underparts are pale grayish.

There are two subspecies and the males can be distinguished by their throat. The entire throat of the O. c. jamesonii subspecies is glittering violet purple, but the O. c. chimborazo subspecies has a violet-purple upper throat and a glittering aquamarine patch on its lower throat. Both have the black chest stripe bordering the throat.

O. c. chimborazo is found around the Chimborazo and Quilotoa volcanoes and the intervening paramo, but O. c. jamesonii is more widespread. It occurs in favorable habitats from southern Columbia to the mountains of Azuay Province, especially around the volcanoes of Cotacachi, Pichincha, Antisana, Iliniza, and Cotopaxi.

A third subspecies, O. c. soderstromi, is thought to be endemic to the volcano Quilotoa in Ecuador. This subspecies, however, has not been recorded since the time of its description. Moreover, the description fits that of an intergrade between the other two subspecies. Both O. c. chimborazo and O. c. jamesonii have been recorded at the type locality of O. c. soderstromi. This third subspecies, thus, may not be a valid one.

Behavior and nesting

Nectar is a very important food for the Ecuadorian hillstar and their main source is the orange flowers of the Chuquiraga shrub. For a hummingbird, its feet are relatively large and instead of hovering while feeding, they usually land and feed while clinging to the plant. This behavior saves energy in the cold environment where they live. Insects are another important food source, many of which are caught in the air or foraged in the vegetation and along the cliffs. At night or when the weather is bad they seek shelter in caves or crevices in ravines. During the night they go into a torpid state to conserve energy.

To protect from the weather, nests are often built in caves or on the walls of steep ravines, usually with an overhang for added protection from hail, rain, and the midday Sun. Some nests are built in protective bushes. The nests are very large for a hummingbird and are built out of warm material like grass, moss, feathers, plant down, horse hair, and rabbit fur. In highly desirable locations, several nests may be found in close proximity. The clutch size is two, and the male does not participate in the nest building, incubation of the eggs, or feeding of the young.

Possible evolutionary importance

Despite its small range, the Ecuadorian hillstar comprises two subspecies. This remarkable case of geographic differentiation has caught the attention of many prominent biologists, among which was Alfred Russel Wallace. In Island Life, Wallace wrote that the ranges of these subspecies were among the most wonderful cases of restricted ranges of any bird.

The presence of the two subspecies is presumed to be related to the complex topography of the Andes, which may have presented numerous opportunities for geographic isolation. Any geographic barrier between both subspecies, however, seems to be absent in the present. Past isolation tied to the varying climate of the Pleistocene may have promoted differentiation within the range of the Ecuadorian Hillstar. Such isolation may not have occurred a long time ago, because no notable differences between the subspecies have been found in mitochondrial DNA.