Orontid dynasty facts for kids

| Orontid dynasty |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Country: | Quick facts for kids Armenia |

||

| Titles: | *King of Greater Armenia

|

||

| Founder: | Orontes I Sakavakyats (legendary) Orontes I (historical) |

||

| Final Ruler: | Orontes IV (Armenia) Mithrobazane II (Sophene) Antiochus IV (Commagene) |

||

| Current Head: | Extinct | ||

| Founding Year: | 6th century BC | ||

| Dissolution: | 200 BC | ||

| Cadet Branches: | Artaxiad dynasty Artsruni dynasty Gnuni dynasty |

||

The Orontid dynasty, also known as the Eruandids, was the first royal family to rule Armenia. They started as governors (called satraps) under the powerful Persian Empire. After the Persian Empire fell, the Orontids became independent kings of Armenia. Later, a part of their family also ruled smaller kingdoms called Sophene and Commagene. They ruled from the 6th century BC until about 200 BC.

Contents

Who Were the Orontids?

Historians aren't completely sure if the Orontids were originally from Persia or Armenia. Some believe they were Persian and connected to the powerful Achaemenid royal family. They often highlighted these connections to make their rule stronger. Other historians think they were Armenian. It's likely they had family ties through marriage to both Persian rulers and important Armenian noble families.

The name "Orontes" comes from an ancient Iranian word meaning "brave" or "hero." In Old Armenian, it was "Eruand," and in modern Armenian, it's "Yervand." This family ruled first from the ancient city of Armavir, which is known as their first capital. Later, they moved their capital to Eruandashat.

The exact date when the Orontid dynasty began is still debated by experts. However, most agree it was after the ancient kingdom of Urartu was destroyed around 612 BC.

Language and Culture

Even though the Greeks invaded Persia, the local Persian and Armenian cultures remained very strong in society and among the leaders.

For official documents, the government used Aramaic for many centuries. Most important writings were also done using Old Persian cuneiform, which is an ancient writing system. Some Armenian villages could speak Persian.

Greek inscriptions found at Armavir show that the upper classes also used Greek as one of their languages. Under Ervand the Last, who ruled around 210–200 BC, the government started to look more like Greek systems. Greek was even used as the language of the royal court. Ervand had many Greek-speaking nobles around him and supported a Greek school in Armavir, his capital city.

Orontid Rulers of Armenia

The Greek historian Xenophon wrote about an Armenian king named Tigranes Orontid in his book Cyropaedia. This Tigranes was a friend and ally of Cyrus the Great, a famous Persian king. Tigranes paid taxes to Astyages, another Median king. When wars broke out, Tigranes stopped following his agreements with the Medes.

After Astyages, Cyrus demanded the same taxes. In 521 BC, the Armenians rebelled after the death of a Persian king. Darius I of Persia sent an Armenian general named Dâdarši to stop the revolt, and later a Persian general named Vaumisa, who defeated the Armenians. Around the same time, another Armenian named Arakha claimed to be the son of the last king of Babylon, but his rebellion was quickly put down.

These events are written in detail on the Behistun Inscription, a famous ancient rock carving. After the Persian Empire was reorganized, Armenia became several satrapies (provinces). Armenian satraps often married into the Persian royal family. These satraps also sent soldiers to help Xerxes invade Greece in 480 BC.

In 401 BC, Xenophon marched through Armenia with a large army of Greek soldiers. He mentioned two people named Orontes, both seemingly Persian. One was a high-ranking military officer who fought against Cyrus the Younger. Xenophon's book Anabasis describes Armenia and mentions that the region was defended by the satrap of Armenia, also named Orontes, son of Artasyras. This Orontes had Armenian soldiers under his command.

In 401 BC, the Persian king Artaxerxes II Memnon gave his daughter Rhodogoune in marriage to Orontes. Later, Antiochus I of Commagene, a king from a branch of the Orontid family, listed this Orontes as one of his ancestors. Another Orontes, possibly the same person, was a satrap of Mysia in 362 BC. He led a revolt of satraps in Asia Minor but later betrayed his fellow rebels. He revolted again and even took the city of Pergamum. Eventually, he made peace with the king. He was honored by the people of Athens in 349 BC. Many coins were made by him during these revolts. All later Orontid rulers were his descendants.

Darius III was the satrap of Armenia after Orontes, from 344 to 336 BC. Armenian soldiers were present at the Battle of Gaugamela under the command of Orontes and Mithraustes. Armenia officially became part of the Macedonian Empire after its rulers surrendered to Alexander the Great. Alexander appointed an Orontid named Mithranes to govern Armenia. After Alexander's death in 323 BC, Armenia was given to a general named Neoptolemus. Around 302 BC, the capital was moved from Armavir to Yervandashat by Orontes.

From 301 BC, Armenia was influenced by the Seleucid Empire, but it kept a lot of its independence and its own rulers. Towards the end of 212 BC, the country was divided into two kingdoms: Greater Armenia and Armenia Sophene (which included Commagene). Both were under the Seleucids. Antiochus III the Great, a Seleucid king, decided to take control of these local dynasties. He attacked Arsamosata, and Xerxes, the ruler of Sophene and Commagene, surrendered. Antiochus gave his sister Antiochis as a wife to Xerxes, but she later murdered him. Greater Armenia was ruled by an Orontid descendant, who was also subdued by Antiochus III. Antiochus then divided the land between his generals Artaxias and Zariadres, who both claimed to be related to the Orontid family.

Orontid Kings of Commagene

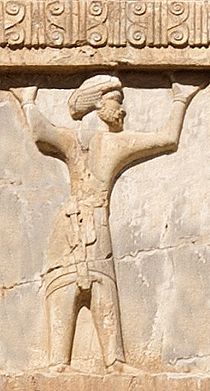

At Nemrut Dağı, a famous ancient site, there are statues of the Greek ancestors of King Antiochos. There is also a row of stone carvings showing his Orontid and Achaemenid ancestors, including Darius and Xerxes. Antiochos worked hard to show everyone that he was related to the great King of Kings, Darius I. This connection came from the marriage of Princess Rhodogune to his ancestor Orontes. Rhodogune's father was the Persian king Artaxerxes. In 401 BC, Artaxerxes defeated his younger brother. Because Orontes, his military commander and satrap of Armenia, helped him, Artaxerxes gave his daughter to Orontes in marriage. A later Orontid descendant, Mithridates I Callinicus, married a Seleucid princess named Laodice VII Thea.

Orontid Kings and Satraps

Here is a list of some important Orontid rulers:

- Orontes I Sakavakyats (570–560 BC)

- Tigranes Orontid (560–535 BC)

- Orontes (401–344 BC)

- Darius Codomannus (344–336 BC)

- Orontes II (336–331 BC)

- Mithranes (331–323 BC)

- Orontes III (317–260 BC)

- Sames of Sophene (Armenia and Sophene around 260 BC)

- Arsames I (260–228 BC) (ruled Armenia, Sophene, and Commagene)

- Xerxes (228–212 BC) (ruled Sophene and Commagene)

- Orontes IV (228–200 BC) (ruled Armenia)

Orontid Kings of Commagene

- Ptolemaeus 163–130 BC

- Sames II Theosebes Dikaios 130–109 BC

- Mithridates I Callinicus 109–70 BC

- Antiochus I Theos 70–38 BC

- Mithridates II 38–20 BC

- Mithridates III 20–12 BC

- Antiochus III 12 BC–17 AD

- Antiochus IV 38–72 AD (and his wife, Iotapa)

See also

In Spanish: Dinastía Oróntida para niños

In Spanish: Dinastía Oróntida para niños

- Artaxiad dynasty

- Commagene

- List of rulers of Commagene

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |