Otto Kallir facts for kids

Otto Kallir (born Otto Nirenstein, April 1, 1894 – November 30, 1978) was an important art historian, writer, publisher, and art gallery owner. He was born in Vienna, Austria, and later moved to New York. He received an award in 1968 for his contributions to Vienna.

Contents

Early Life and Career in Austria

Otto Nirenstein went to high school in Vienna from 1904 to 1912. After serving in the Austrian Army during World War I, he wanted to become an aeronautical engineer. However, because of unfair treatment against Jewish people at the technical institute, he changed his plans.

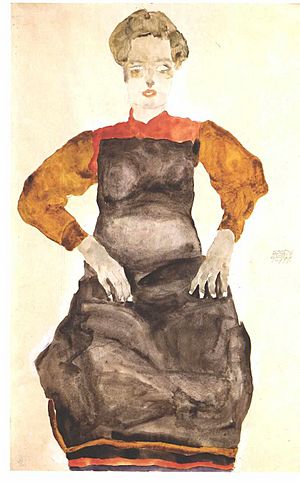

In 1919, he started a publishing company called Verlag Neuer Graphik. One of his most important publications was a collection of works by the artist Egon Schiele. In 1923, Nirenstein opened the Neue Galerie (New Gallery) in Vienna. Its first big show featured Schiele's art after the artist had passed away.

Nirenstein became a well-known art dealer around the world. He represented famous artists like Gustav Klimt, Oskar Kokoschka, Egon Schiele, and Alfred Kubin. In 1931, he helped bring the art of Richard Gerstl back into public view. He also saved the belongings of the poet Peter Altenberg, creating a special display of his old hotel room.

The Neue Galerie also showed art by modern Austrian artists and older masters. Nirenstein even brought European modern art, like works by Edvard Munch and Vincent van Gogh, to Austria when it was still new there.

In 1922, Nirenstein married Franziska von Löwenstein-Scharffeneck. The next year, when their son John was born, he changed his publishing company's name to Johannes Presse. This company also focused on special limited-edition books with original art prints. Their daughter, Evamarie, was born in 1925.

In 1928, Nirenstein worked with an artists' group called the Hagenbund. They put on a big exhibition to remember Egon Schiele ten years after his death. Two years later, Nirenstein published the first complete list of all Schiele's paintings.

In 1930, he earned his doctorate in art history from the University of Vienna. In 1933, Otto Nirenstein legally changed his last name to Kallir, a name that had been in his family for many generations.

Moving to the United States

When the Nazis took over Austria in 1938, Kallir was in danger because he was Jewish and had supported the previous government. He had to leave Austria. He sold his Neue Galerie to his secretary, Vita Künstler, who was not Jewish. She protected the gallery and later gave it back to Kallir after World War II.

Kallir was able to take many artworks with him when he left. This was because the modern art he dealt with was not subject to export laws and was considered "degenerate" by the Nazis. He first went to Switzerland, then to Paris, France. In Paris, he opened the Galerie St. Etienne, named after a famous cathedral in Vienna.

However, his family could not join him in France. So, in 1939, they all moved to the United States. They brought a large part of the gallery's art collection with them.

In the same year, Kallir opened the New York Galerie St. Etienne. Here, he introduced American audiences to Austrian and German expressionist art.

Helping Austrian Refugees

In Paris, Kallir became friends with Otto von Habsburg, who was a claimant to the Austrian throne. Soon after arriving in New York, Kallir joined the Austrian-American League. This group helped Austrian refugees. He became its chairman in 1940.

The League organized events and helped new arrivals settle into life in the US. As chairman, Kallir worked hard to get US visas for persecuted Austrians. He helped about 80 refugees find safe passage to America.

Kallir was also worried that if the US entered the war, Austrians living there might be treated as enemies. In 1941, he convinced Otto von Habsburg to go with him to Washington D.C. They met with the Attorney General and explained that Austrians were victims of Hitler, not his helpers. In 1942, after the US joined the war, Austria was officially recognized as a neutral country. This helped Austrians living in the US.

Clearing His Name

A man named Willibald Plöchl led a rival group to the Austrian-American League. He blamed Kallir for disagreements he had with Otto von Habsburg. Because of this, members of Plöchl's group wrongly told the FBI that Kallir was a "former agent of Hitler and Mussolini" and had dealt with stolen art.

These false accusations caused Kallir to have a serious heart attack in December 1942. After he recovered, he left the Austrian-American League and stopped being involved in politics. A newspaper that had printed the false story about Kallir apologized. The FBI closed its investigation, with J. Edgar Hoover confirming that the accusations were based on jealousy from a rival group and were not true.

Art World in the United States

When Kallir opened the Galerie St. Etienne in New York in 1939, Austrian modern artists were not well known or valuable internationally. At Egon Schiele's first American exhibition in 1941, drawings were priced at $20 and watercolors at $60, but none sold.

Through many exhibitions, sales, and gifts to museums, Kallir slowly built the reputations of artists like Schiele, Gustav Klimt, Oskar Kokoschka, and Alfred Kubin. The Galerie St. Etienne held the first American solo shows for artists such as Erich Heckel (1955), Klimt (1959), and Paula Modersohn-Becker (1958).

In the 1940s, when Austrian art was hard to sell, Kallir found great success with the self-taught painter Anna Mary Robertson Moses. Known as "Grandma Moses," she became one of the most famous artists of her time and the most successful female painter.

Kallir worked closely with museums and focused on art scholarship. In 1960, he helped organize the first American museum exhibition of Schiele's work. In 1965, he convinced Thomas Messer, the director of the Guggenheim Museum in New York, to put on a major Klimt and Schiele show.

In 1966, Kallir published an updated complete list of Schiele's paintings. In 1970, he published a complete list of Schiele's prints. To thank the Guggenheim Museum, Kallir donated Schiele’s "Portrait of an Old Man (Johann Harms)" in 1969. He also made other important donations, like Klimt’s "Pear Tree" to the Fogg Art Museum in 1956 and "Baby" to the National Gallery of Art in 1978.

He also wrote complete lists of works for Grandma Moses (1973) and Richard Gerstl (1974).

After Kallir's death in 1978, his long-time associate, Hildegard Bachert, and his granddaughter, Jane Kallir, took over the Galerie St. Etienne. In 2020, the gallery stopped selling art and became an art advisory. Its historical records and library were moved to the Kallir Research Institute, a foundation started in 2017 to continue Otto Kallir’s scholarly work.

The Neue Galerie in Vienna closed in 1975. Its records were given to the Belvedere Gallery. Otto Kallir's family donated his collection of historical signatures to the Wienbibliothek im Rathaus in 2008. More of his historical materials can be found at the Galerie St. Etienne and the Leo Baeck Institute in New York.

Helping Recover Stolen Art

After World War II, Kallir realized that many people who stayed in Austria had cooperated with the Nazis. Because he knew a lot about art collections from before the war and had connections with refugees, Kallir made a special effort to help collectors get back art that had been stolen during the Nazi years.

Often, he faced strong resistance from Austrian museums and legal groups. However, in 1998, Kallir's records helped in the seizure of a stolen Schiele painting, Portrait of Wally. This painting was on loan from Austria to the Museum of Modern Art in New York. This case led Austria to change its laws, allowing many stolen artworks to be returned to their rightful owners.

One example was Edvard Munch’s “Summer Night on the Beach.” This painting was returned in 2006 to the granddaughter of Alma Mahler Werfel. Kallir had tried to help Mahler Werfel get the painting back after the war, and his records were very important in the later effort to recover it.

Art Dealing During the Nazi Era

Some people have wondered about Kallir's actions during the Nazi era. However, a closer look shows that any suggestions of wrongdoing are not true. For example, letters found in 2007 described an art sale to a Nazi agent as Kallir was trying to escape Austria after the Nazis took over. The letters show that Kallir was pressured by both the agent and the painting's owner, who was clearly a Nazi. Kallir did not make any money from this sale and later wrote to the owner, saying the whole situation was "extremely unpleasant."

There have been some legal cases about artworks that Kallir handled. In one case involving Schiele's watercolor “Woman Hiding Her Face” (1912), a judge ruled in favor of the family of a Holocaust victim, Fritz Grünbaum. Kallir had bought this artwork in 1956 and sold it a year later for $300. The painting had been sold many times and became much more valuable by 2013.

In an earlier case about another Schiele painting, “Seated Woman with Bent Left Leg” (1917), the judge ruled in favor of the owner. The judge stated that after much research, there was no concrete evidence that the Nazis had stolen the drawing or that it was taken from Grünbaum.

Awards

- 1968: Silbernes Ehrenzeichen für Verdienste um das Land Wien (Silver Medal of Honor for Services to the City of Vienna)

See Also

- German Expressionism

- The Holocaust in Austria

- Eberhard Kornfeld

- Fritz Grünbaum

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |