Oskar Kokoschka facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Oskar Kokoschka

|

|

|---|---|

Oskar Kokoschka in 1963, by Erling Mandelmann

|

|

| Born | 1 March 1886 Pöchlarn, Austria-Hungary

|

| Died | 22 February 1980 (aged 93) Montreux, Switzerland

|

| Nationality |

|

| Known for | Painting, printmaking, poetry, play writing |

| Movement | Expressionism |

Oskar Kokoschka (born March 1, 1886 – died February 22, 1980) was a famous Austrian artist. He was also a poet, playwright, and teacher. He is best known for his powerful and emotional portraits and landscapes. His unique style is part of a movement called Expressionism. His ideas about how we see things also influenced other artists in Vienna.

Contents

Early Life and Art Dreams

Oskar Kokoschka was born in Pöchlarn, Austria. He was the second child of Gustav Josef Kokoschka, a goldsmith. His family often struggled financially and moved to smaller homes. Oskar felt very close to his mother. He saw himself as the head of the family. He helped support them once he became financially independent.

In 1897, Oskar went to a secondary school called a Realschule. This school focused on modern subjects like science. But Oskar was not interested in these subjects. He only did well in art. He spent most of his time reading classic books. Like many artists of his time, he was fascinated by "primitive" and "exotic" art. He saw these types of art in exhibits across Europe.

Becoming an Artist

One of Oskar's teachers noticed his talent for drawing. The teacher suggested he become an artist. Oskar decided to apply to the Kunstgewerbeschule in Vienna. This was a school for applied arts. He got a scholarship and was accepted. This was against his father's wishes.

The Kunstgewerbeschule was a modern art school. It focused on architecture, furniture, and design. It was different from the more traditional Academy of Fine Arts Vienna. Oskar studied there from 1904 to 1909. His teacher, Carl Otto Czeschka, helped him develop his unique style.

Oskar's early works included drawings of children. He drew them in an unusual, almost doll-like way. He didn't have formal painting training. So, he painted in his own way, not following old rules. The school helped him get jobs through the Wiener Werkstätte. His first jobs were drawing postcards and pictures for children. He later said this work taught him the basics of art. He also painted portraits of famous people in Vienna. These paintings had a very lively and emotional style.

Oskar also spent years teaching art. He wrote about his ideas on education. He was influenced by John Amos Comenius, a 17th-century educator. Oskar believed students learn best by using their five senses. He taught in Vienna and Dresden. He didn't use strict teaching methods. Instead, he told stories with myths and strong emotions.

In 1912, Oskar wrote an essay called "On the Nature of Visions." He talked about how inner thoughts and what we see connect. He believed his art came from daily observations. But these observations were then shaped by his imagination. This idea helped define Viennese Expressionism.

Art Career Highlights

Vienna's New Art Scene

In 1908, Oskar had a chance to show his art at the first Vienna Kunstschau. This exhibition aimed to attract tourists and show Vienna's importance in art. Oskar was asked to create colorful images for a children's book. But he decided to illustrate a poem he wrote instead. The poem, Die träumenden Knaben (The Dreaming Youths), was a personal fantasy. It was not really for young children.

The book had small black and white drawings. It also had eight larger color drawings with text. Oskar was inspired by medieval art. He showed different moments in time within one image. He used bold lines and bright colors like folk art. He combined this with the fancy style of Jugendstil. This work showed his move from Jugendstil to Expressionism.

Die träumenden Knaben and a tapestry called The Dream Bearers were Oskar's first public works. People found them unsettling. As a result, he was expelled from the Kunstgewerbeschule. But this led him to the exciting new art scene in Vienna. Architect Adolf Loos became his friend. Loos introduced him to other modern artists. Many of these artists became subjects for Oskar's portraits.

Expressive Portraits

Oskar painted many portraits between 1909 and 1914. Unlike other artists, he had full artistic freedom. His portraits were often ordered by Adolf Loos, not directly by the people he painted. Many of his subjects were friends and supporters of modern art. These included art dealer Herwarth Walden and art historians Hans and Erica Tietze.

Oskar's portraits used traditional ideas. But he also added modern touches. He often included hands in his paintings. He believed hands showed a person's emotions. He also thought that how a person's body was positioned could reveal their inner feelings.

His portraits used bright, expressive colors. These were similar to the German Die Brücke artists. He used bold lines and patches of bright color. These were set against dull backgrounds. This showed the anxiety felt by people at the time. Oskar's portraits were unique because he showed his painting process. You could see his brushstrokes and even parts of the canvas. He mixed painting and drawing techniques. He used vibrant colors, quick brushstrokes, and scratch marks.

In 1909, Oskar wrote that he wanted to paint a "nervously disordered portrait." He believed the essence of a person came out through the act of painting. Art historian Patrick Werkner said Oskar's portraits made it seem like you could see through the skin. This revealed the deeper meaning of the painting. His portraits showed the uncertainty people felt as the old Austrian Empire changed.

One famous portrait is Hans Tietze and Erica Tietze-Conrat, painted in 1909. The couple were close friends and art historians. Oskar painted them in their library. He encouraged them to move freely. He used his fingers and fingernails to scratch lines into the paint. This created outlines and textures. The painting uses bright blues and reds against a muted green background. The couple don't face each other. But their hands reach out as if to touch. Their hands become a way for their inner feelings to connect. The couple had to leave Austria in 1938 because they were Jewish. They took this portrait with them. They refused to show it until it was bought by the Museum of Modern Art in 1939.

Moving to Berlin

Oskar moved to Berlin in 1910. This was when the Neue Secession art group was formed. This group included artists like Emil Nolde and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. They rebelled against older art groups. Oskar admired their sense of community.

Art dealer Paul Cassirer saw Oskar's talent. He helped Oskar become known internationally. Around the same time, Herwarth Walden, a publisher, hired Oskar. Oskar became an illustrator for his magazine Der Sturm. He contributed many drawings and even wrote for the magazine. He traveled between Vienna and Berlin for the next four years.

Oskar had a strong connection with Alma Mahler. This relationship inspired one of his most famous works, The Bride of the Wind (also called The Tempest; 1913). This painting shows the deep emotions of their bond.

World War I and Beyond

Oskar joined the Austrian army in World War I. In 1915, he was seriously wounded. He continued his art career, traveling and painting landscapes.

In 1919, Oskar started teaching at the Kunstakademie Dresden. In 1920, he wrote an open letter to the people of Dresden. He asked that civil war battles be moved outside the city. He wanted to protect art from damage. This letter caused a debate among artists. But many still supported Oskar's work.

In 1922, he joined the International Congress of Progressive Artists. He signed a statement to form a union of international artists.

In 1931, Oskar returned to Vienna. He lived in a house he bought for his parents. He painted a picture for the City Council of Vienna. It showed children playing outside a palace. It also included famous Vienna buildings like City Hall.

Facing "Degenerate Art"

The Nazis called Oskar's art "degenerate" (meaning bad or harmful). In 1934, he had to leave Austria and went to Prague. He became a Czechoslovak citizen in 1935. In 1938, as the Nazis threatened invasion, he fled to the United Kingdom. He stayed there during World War II. Many other artists he knew also escaped with help from refugee groups.

During the war, Oskar painted works against the Nazis. One was What We Are Fighting For (1943). He moved to Polperro, a village in England. There, he painted landscapes of the harbor. He also painted The Crab (1939-1940). This painting used symbols to protest the Nazi regime. Oskar said the crab, representing the British Prime Minister, "would only have to put out one claw to save him from drowning, but remains aloof." This showed his feelings of instability. He also painted The Red Egg, a satirical painting about the destruction of Czechoslovakia. It showed funny, exaggerated images of Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler.

He and his wife, Olda, also spent summers in Scotland. He drew with colored pencils and painted watercolors of the landscapes. He painted a portrait of his friend Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer there. This painting is now in the Kunsthaus Museum in Zurich.

Later Life and Legacy

Oskar became a British citizen in 1947. He later regained Austrian citizenship in 1978. In 1953, he settled in Villeneuve, Switzerland. He lived there for the rest of his life. He taught at an international art academy. He also designed stage sets and published his writings.

In 1962, a large show of his work was held at the Tate Gallery in London. He also participated in important art exhibitions called documenta. In 1966, he won a competition to paint a portrait of Konrad Adenauer, a German leader.

Oskar Kokoschka passed away on February 22, 1980, in Montreux, Switzerland. He was 93 years old. He is buried in the Montreux Central Cemetery.

Oskar Kokoschka had much in common with another artist, Max Beckmann. Both were unique and didn't fully fit into the main German Expressionism movement. Yet, they are now seen as key examples of the style. Both wrote about the importance of "seeing" in art. Oskar focused on how we see depth. Both were masters of oil painting techniques.

Honours

Oskar Kokoschka received several awards. He was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1959. He also won the Erasmus Prize in 1960 with Marc Chagall.

Artworks

- 1909: Lotte Franzos

- 1909: Martha Hirsch I

- 1909: Hans and Erika Tietze

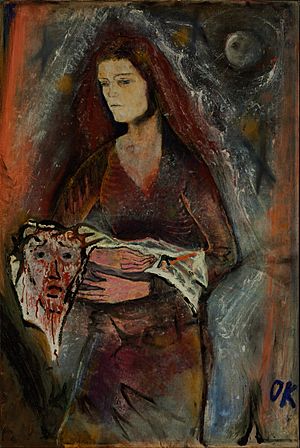

- 1909: St. Veronica with the Sudarium

- 1909: Les Dents du Midi

- 1909: Children Playing

- 1910: Still Life with Lamb and Hyacinth

- 1910: Rudolf Blümner

- 1911: Lady in Red

- 1911: Hermann Schwarzwald I

- 1911: Egon Wellesz

- 1911: Crucifixion

- 1913: Landscape in the Dolomites (with Cima Tre Croci)

- 1913: The Tempest

- 1913: Carl Moll

- 1913: Still Life with Putto and Rabbit

- 1914: The Bride of the Wind

- 1914: Portrait of Franz Hauser

- 1915: Knight Errant

- 1917: Portrait of the Artist's Mother

- 1917: Lovers with Cat

- 1917: Stockholm Harbour

- 1920: The Power of Music

- 1919: Dresden, Neustadt I

- 1921: Dresden, Neustadt II

- 1921: Two Girls

- 1922: Self-Portrait at the Easel

- 1923: Self-Portrait with Crossed Arms

- 1924: Venice, Boats on the Dogana

- 1925: Amsterdam, Kloveniersburgwal I

- 1925: Toledo

- 1926: Mandrill

- 1926: Deer

- 1926: London Large Thames View I

- 1929: Arab Women and Child

- 1929: Pyramids at Gizeh

- 1932: Girl with Flowers

- 1934: Prague, View from the Villa Kramář

- 1936: Portrait Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer

- 1937: Olda Palkovská

- 1938: Prague – Nostalgia

- 1940: The Crab

- 1941: Anschluss – Alice in Wonderland

- 1941: The Red Egg

- 1948: Self-Portrait (Fiesole)

- 1950: The Myth of Prometheus

- 1962: Storm Tide in Hamburg

- 1966: The Rejected Lover

- 1966: Portrait of Konrad Adenauer

- 1971: Time, Gentlemen, Please

Writings and Plays

Oskar Kokoschka's writings are as unique as his art. His memoir, A Sea Ringed with Visions, talks about his ideas on vision and how it shapes art. His short play Murderer, the Hope of Women (1909) is often called the first Expressionist drama. His play Orpheus und Eurydike (1918) was later turned into an opera.

First Productions of Plays

- 1907: Sphinx und Strohmann. Komödie für Automaten. First shown in 1909 in Vienna.

- 1909: Mörder, Hoffnung der Frauen

- 1911: Der brennende Dornbusch

- 1913: Sphinx und Strohmann, Ein Curiosum. First shown in 1917 in Zürich.

- 1917: Hiob (a longer version of Sphinx und Strohmann)

- 1919: Orpheus und Eurydike

- 1923: New version as an opera story; music by Ernst Krenek. First shown in 1926.

- 1936–38/1972: Comenius

Articles and Essays

- 1960: "Lettre de Voyage", Oskar Kokoschka, X magazine, Vol. I, No. II (March 1960)

See Also

In Spanish: Oskar Kokoschka para niños

In Spanish: Oskar Kokoschka para niños

- Facing the Modern: The Portrait in Vienna 1900

Literature

- Alfred Weidinger: Oskar Kokoschka. Dreaming Boy and Enfant Terrible. Early Graphic Works, 1902–1909. Ed. Albertina, Vienna 1996.

- Alfred Weidinger: Kokoschka and Alma Mahler: Testimony to a Passionate Relationship. Prestel, New York 1996, ISBN: 3-7913-1722-9

- Tobias G. Natter, (Ed.), Oskar Kokoschka. The Early Portraits 1909–1914, exhibition catalog Neue Galerie New York and Hamburger Kunsthalle. DuMont, Cologne 2001, ISBN: 3-8321-7182-7.

- Paul Westheim, Oskar Kokoschka : das Werk Kokoschkas in 135 Abbildungen, exhibition catalogue, Paul Cassirer Verlag, Berlin, 1925.

Filmography

- Kokoschka Life's work, documentary directed by Michel Rodde, Switzerland, 2017, 91', distributed in Canada by K-Films Amérique (VOD).

Images for kids

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |