Patricia Johanson facts for kids

Patricia Johanson (born September 8, 1940 – died October 16, 2024) was an American artist. She was famous for creating huge art projects. These projects were designed to be beautiful and useful. They made good homes for both people and wildlife.

Her art often helped solve problems with cities and the environment. It also helped people living in cities feel more connected to nature. She started designing these projects in 1969. This made her a leader in a field called ecological art, or eco-art. Her work is also known as Land Art, Environmental Art, and Garden Art. Her first paintings and sculptures were part of a style called Minimalism.

Contents

- Growing Up and Learning About Art

- Early Minimalist Artworks

- Designing Gardens and Landscapes

- Major Art Projects

- Fair Park Lagoon, Dallas (1981–1986)

- Endangered Garden, San Francisco (1987–1997)

- Park for the Amazon Rainforest, Obidos, Brazil (1992)

- The Rocky Marciano Trail, Brockton, Massachusetts (1997–1999)

- Millennium Park Landfill Site, Seoul, Korea (1999)

- Petaluma Wetlands Park and Ellis Creek Water Recycling Facility, Petaluma, California (2001–2009)

- The Draw at Sugar House, Salt Lake City, Utah (2003–2018)

- Mary’s Garden, Marywood University, Scranton, Pennsylvania (2008-present)

- McMarsh and West Campus, McMaster University (2018-present)

- What People Say About Patricia Johanson

- Art Collections with Patricia Johanson's Work

- Selected Exhibitions

- Awards and Honors

Growing Up and Learning About Art

Patricia Johanson loved nature and art from a young age. She grew up in New York City. There, she spent many hours in parks designed by Frederick Law Olmsted. Her mother, who used to be a model, introduced her to the arts.

In high school, she was very good at music. But at Bennington College (1958–1962), she chose to study painting. At Bennington, she met important people in the New York art world. Her teacher, Tony Smith (sculptor), became a close friend. Her art history professor, Eugene Goossen, was a mentor and later her husband. She also met other famous artists like Kenneth Noland and Helen Frankenthaler.

Johanson earned a Master's degree in art history from Hunter College in 1964. There, she continued to study with Tony Smith and Eugene Goossen. She also met future artists like Robert Morris. She worked as a researcher for a publisher. This job led her to help organize the work of artist Georgia O'Keeffe. O'Keeffe became a very important mentor to her.

Her husband, Eugene Goossen, passed away in 1997. Patricia Johanson died on October 17, 2024, at 84 years old.

Early Minimalist Artworks

In the 1960s, Johanson made paintings and sculptures in the Minimalism style. Her work was shown in some of the first Minimal Art exhibitions. These included "8 Young Artists" (1964) and "Cool Art" (1968). Her Minimalist paintings used simple lines. They explored how colors affect what we see.

Her paintings were shown at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery in New York. A long oil painting, "William Clark," was part of a 1968 show at the Museum of Modern Art. Another 28-foot-long painting, "Minor Keith," was shown in 2004. The Art Institute of Chicago bought it in 2023.

Johanson started making large Minimal sculptures in 1966. One piece, William Rush, used 200 feet of painted steel beams laid on the ground. In 1968, she made Stephen Long, which was 1600 feet long. It used painted plywood pieces along an old railroad track. These large outdoor sculptures showed that art could be too big to see all at once. This idea is still important in her work today.

Her sculpture Cyrus Field (1970–71) was a turning point. It was still a large Minimalist piece. But it used natural marble, cement, and redwood. She created a maze of lines that led visitors through a forest. This showed how the natural landscape changed. With this work, she started to use lines to include nature, not just replace it. She also found a way to connect human size with the vastness of nature.

Designing Gardens and Landscapes

In 1969, House & Garden magazine asked Johanson to design a garden. Even though it was never built, this request sparked many new ideas. She made 150 small sketches. These drawings were very different from traditional garden designs. They also went against the art ideas of the 1960s. Instead of "art for art's sake," her garden designs were meant to be useful and meaningful.

Johanson stopped making traditional paintings and sculptures. She started focusing on designs that were both art and landscape. To prepare for these big projects, she studied civil engineering and architecture. She earned her architecture degree in 1977.

Plant Drawings for Projects (1974–1978)

In the 1970s, Johanson started a family. She moved to a farmhouse in upstate New York. This meant she was always close to nature's seasons. But raising children left her with little time to work.

Her solution was to make tiny drawings of plants during the day. At night, she turned them into designs for huge projects. She also studied books about plants. This new way of working meant she drew nature exactly as it was, rather than just from imagination.

Water and Color Garden Designs (1980–1985)

In the 1980s, Johanson began her first built projects. She also created many drawings for gardens and fountains. These designs used water and color. They often looked like giant flowers, butterfly wings, or snakes.

For example, Tidal Color Gardens (1981–82) made ocean tides more visible. They used images of butterfly wings or flowers that changed as water flowed in and out. The O’Keeffe/Equivalents-Color Garden drawings were for earth sculptures. These sculptures looked like butterfly wings. Their color patterns were based on photos of Georgia O'Keeffe.

Major Art Projects

Fair Park Lagoon, Dallas (1981–1986)

Johanson's first big project was in 1981. She was asked to fix the Fair Park Leonhardt Lagoon in Dallas. The lagoon was in very bad shape. Its shoreline was falling apart, the water was dirty, and too much algae was growing.

Johanson designed large sculptures to solve these problems. They broke up waves and helped the water. She also chose local plants to create small homes for wildlife. The huge, terra cotta-colored sculptures were made of a material called gunite. They looked like a Delta Duck-Potato plant and a Spider Brake Fern. These sculptures also worked as paths for people and resting spots for birds and turtles.

Today, Leonhardt Lagoon is a healthy ecosystem in Dallas. It's also a place for learning and fun. This project is one of the first examples of art helping to clean up nature. For this and other large city projects, she worked with many experts. These included scientists, engineers, city planners, and local community groups.

Endangered Garden, San Francisco (1987–1997)

San Francisco needed a new pump station and water tank near the Bay. Johanson was asked to help design it. She wanted it to be beautiful and useful. So, she designed a series of habitats to help animals that were in danger.

The roof of the sewer building became a long walkway. Its colors and patterns came from the endangered San Francisco garter snake. The "head" of the snake was a 20-foot-high mound. This mound was a small home for butterflies. The Ribbon Worm Tidal Steps filled with water when the tide was high. This created homes for small sea creatures.

Park for the Amazon Rainforest, Obidos, Brazil (1992)

In 1992, the Brazilian government invited Johanson to the Earth Summit. They also asked her to create a park project in the Amazon Rainforest. Her design showed a 150-foot-high ramp. It was shaped like a Brazilian plant. This ramp would let visitors see different small habitats at various levels. The ramp itself was meant to be covered by tropical plants over time. This project has been put on hold many times due to changes in the government.

The Rocky Marciano Trail, Brockton, Massachusetts (1997–1999)

This project aimed to help the economy of Brockton. Johanson planned to connect different neighborhoods and restore nature. Since Rocky Marciano was a famous boxer from Brockton, she used his training routes. These routes would connect neighborhoods and nature.

The trail would start at Marciano's home. It would lead visitors to special places like Thomas McNulty Park. Johanson also planned to uncover buried streams. She wanted to bring back forest areas to create a continuous public landscape. However, the city of Brockton did not approve this project.

Millennium Park Landfill Site, Seoul, Korea (1999)

In 1999, Johanson was part of a team asked to find solutions for Seoul’s main garbage dump. The dump had closed in 1990. Her idea was to turn the site into a park. She wanted to bring back natural plant and animal communities.

She chose the haetae as a main image. This is a mythical animal that protects against evil. She used patterns from haetae sculptures to design terraces and small habitats. These designs also helped people and vehicles reach the park's highest points.

Petaluma Wetlands Park and Ellis Creek Water Recycling Facility, Petaluma, California (2001–2009)

Johanson worked with engineers to create a new water treatment facility. She combined art, public access, sewage treatment, and nature restoration. Her design made a major city system part of living nature. People have said her design "re-invented art and reformed civil engineering."

The project uses natural systems to treat sewage. This allows millions of gallons of water to be reused. Johanson used the shape of the endangered Salt Marsh Harvest Mouse for the polishing ponds. These ponds have islands that guide water flow. They also provide nesting places for birds. Other plants support local wildlife. An extra 230 acres of tidal wetlands were added for the park. This park offers over 3 miles of walking trails for learning and nature study.

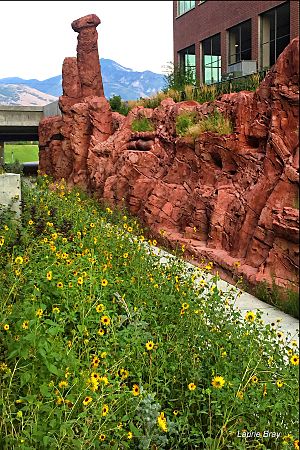

The Draw at Sugar House, Salt Lake City, Utah (2003–2018)

A local group asked Johanson to create a safe path under a busy highway. This path would connect two parts of a planned trail. Her design includes two giant sculptures. They are based on the native Sego Lily flower and a historic canyon. These are on either side of the highway and connected by an underpass.

The Sego Lily sculpture acts as a dam to redirect water. The canyon part works as a flood wall and provides homes for wildlife. At the same time, the sculptures are climbing walls, viewpoints, a trail, and a plaza. The underpass looks like a Utah canyon. It has fake coal layers and fossil shapes.

Like her other projects, The Draw at Sugar House has many layers. It is a huge sculpture, a home for local plants and animals, and a way to learn about Utah's history. It is also part of Salt Lake City's flood control system. The project is known for its complex design. It needed advanced engineering with strong beams and concrete.

The Draw started in 2003 as a design for a safe path for bikes and walkers. This path goes under a busy seven-lane highway. It connects two parts of Parley's Creek Trail. The original design changed over 15 years. Its flood control features were improved.

The final artwork has three connected parts. These are the Sego Lily plaza, the underpass, and the Echo Canyon "living wall." You can enter and explore it from either side.

The Sego Lily Plaza has many uses and meanings. The design is based on Utah's state flower, the sego lily. The flower's shapes create an amphitheater. Its stem forms a path leading to a bulb-shaped viewpoint. This viewpoint is above Parley's Creek. The three petals of the giant lily have sculpted rock-like forms. These create small terraces for native plants and places for visitors to sit. When there is flooding, the bowl-shaped amphitheater collects water. It then guides the water through the underpass and down the sculpted "canyon."

When you enter the underpass from Sego Lily Plaza, you see things that look like Utah's underground geology. There's a slice of rocky layers with a clear coal seam. You can also find small details like fossils and roots.

West of the tunnel is a sculpted floodwall. It helps guide overflowing water to Parley's Creek. The shapes of the wall look like natural landmarks from Utah's historic Echo Canyon. This canyon helped Mormon pioneers find their new land. This small Echo Canyon is part of the flood control system. It's also a historical reference. Plus, it's a vertical garden with nesting spots, water collection basins, and ledges. These provide homes for native animals and plants.

Mary’s Garden, Marywood University, Scranton, Pennsylvania (2008-present)

Mary’s Garden is designed to fix a former coal mining site. The garden cleans water and provides homes for wildlife. It also tells the story of the area's culture, geology, and nature. Two large sculptures, Madonna Lily and Mary’s Rose, shape the two main areas. They are based on traditional religious symbols. Parts of the mining activity and forms made of local rock show the land's past industrial uses. Seating and paths offer places to relax and observe plants and wildlife.

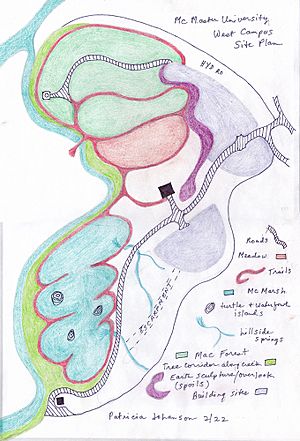

McMarsh and West Campus, McMaster University (2018-present)

This 45-acre project is still being built at McMaster University in Canada. It will be a work of Land Art, a restored wetland, and a living lab for students.

The overall design looks like a Monarch butterfly wing. This honors the endangered Monarch butterfly. These butterflies start their long journey to Mexico from this part of Ontario. The wing shape is made by landscaped terraces, plants, and Coldwater Creek. The upper and lower parts of the wing will have two main habitat areas. Inside these habitats, unpaved paths will let visitors see the different natural areas up close. These paths are inspired by the veins of a Monarch's wings.

Johanson’s design is a big part of the University’s plan for its West Campus. It will bring back three different wetland habitats: wet forest, ponds, and marshland. These will be in the upper and lower sections of the Monarch wing shape.

In the upper section, new woodlands will be added to the existing McMaster Forest. This will create a cooler, more sustainable environment. Within the forest, a separate food forest will grow plants used by local Indigenous groups. Next to the forest will be two meadows. These will include milkweed plants, which Monarch caterpillars eat.

In the southern part, called McMarsh, the current parking lot will be dug out. It will be replaced by four connected ponds. Native plants here will help clean water. They will also provide food and shelter for birds, waterfowl, amphibians, and turtles. Paths around and into the ponds will let visitors study wildlife up close. A deep channel will allow researchers to use canoes and kayaks.

The soil dug out for the ponds will be used to shape the land. Some of it will be sculpted to look like local geology, like the Niagara Escarpment. Some will be shaped to direct rainwater or air flow. Some will form flat areas for a research center. This center will study how the new habitats change over time.

What People Say About Patricia Johanson

Many people see Patricia Johanson as a leader in eco-art. Her early writings from the late 1960s were full of ideas for environmental art. These ideas are still being discovered today.

Her work focuses on ecosystems and survival. She creates art that brings natural environments back to life. She also helps city people connect with nature. This makes her an innovator in art, ecology, and city renewal.

People say that Johanson teaches us that artists can be important forces. They can create social and environmental change.

Art Collections with Patricia Johanson's Work

- Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Oberlin, Ohio

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- Museum of Modern Art, New York

- National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D. C.

- Storm King Art Center, Mountainville, New York

Selected Exhibitions

- 2023 “Groundswell: Women of Land Art,” Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas, Texas

- 2022 “Visual Natures: The Politics and Culture of Environmentalism in the 20th and 21st Centuries,” MAAT, Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology, Lisbon, Portugal

- 2020 “Patricia Johanson: House & Garden,” Usdan Gallery, Bennington College, Bennington, Vermont

- 2018 “Virginia Woolf: An Exhibition Inspired by Her Writings,” Tate St. Ives; Pallant House, Chichester; and Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge University, UK

- 2018 “Shifting Ground,” Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University

- 2017 “Hybris,” MUSAC, Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Castilla y León, Spain

- 2015 “Patricia Johanson’s Environmental Remedies: Connecting Soil to Water,” Millersville University, Millersville, Pennsylvania

- 2014 “Beyond Earth Art,” Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York

- 2013 “Patricia Johanson: The World as a Work of Art,” Museum Het Domein, Sittard, The Netherlands

- 2013 “My Brain Is in My Inkstand: Drawing as Thinking and Process,” Cranbrook Art Museum, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- 2012 “Ends of the Earth: Land Art to 1974,” Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles and Haus der Kunst, Munich

- 2012 “Green Acres: Artists Farming Fields, Greenhouses and Abandoned Lots,” Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati

- 2010 “Elemental: Earth, Air, Fire, Water,” Santa Fe Art Institute, New Mexico

- 2009 “Art and Infrastructure: Patricia Johanson and the Petaluma Wetlands Park,” Nevada Museum of Art, Reno

- 2007 “Weather Report: Art and Climate Change,” Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art, Colorado

- 2004 “A Minimal Future? Art as Object: 1958-1968,” Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

- 2002 “Ecovention: Current Art to Transform Ecologies,” Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati

- 2001 “Patricia Johanson: An Artist’s Vision for Community,” Salina Art Center, Kansas

- 2000 “Jardin 2000: La Ville/Le Jardin/La Memoire,” Accademia di Francia, Villa Medici, Rome

- 2000 “French Embassy Garden Competition,” Ambassade de France, Cultural Services Gallery, New York

- 2000 “Un Jardin à Manhattan,” l’Institut Français d’Architecture, Paris

- 1994 “Creative Solutions to Ecological Issues,” Laumeier Sculpture Park, St. Louis and Longwood Fine Art Center, Virginia

- 1994 “Cosmic-Maternal: Lia do Rio, Patricia Johanson, Mariyo Yagi,” Gallery Nikko, Tokyo

- 1993 “Tres Cantos da Terra,” National Museum of Fine Arts, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

- 1993 “Differentes Natures,” La Defense Art Galleries, Paris and La Virreina, Barcelona

- 1992 “Fragile Ecologies: Artists Interpretations and Solutions,” Queens Museum, Flushing, New York

- 1992 “Projeto Omame,” Movimento Artistas Pela Natureza, Athos Bulcão Art Gallery, National Theater, Brasilia, Brazil

- 1991 “Patricia Johanson: Public Landscapes,” Painted Bride Art Center, Philadelphia

- 1991 “Patricia Johanson, A Retrospective, 1960-1991,” Usdan Gallery, Bennington College, Vermont

- 1991 “Eco Art: Imaging a New Paradigm,” San Jose State University, California

- 1987 “Patricia Johanson: Interpretive Drawings for Architecture and Landscape,” Twining Gallery, New York

- 1987 “Patricia Johanson: Drawings and Models for Environmental Projects, 1969-1986,” Berkshire Museum, Pittsfield, Massachusetts

- 1986 “Sculpture for Public Spaces,” Marisa del Re Gallery, New York

- 1986 “Awards Exhibition,” American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, New York

- 1985 “The Maximal Implications of the Minimal Line,” Bard College, Annandale-on- Hudson, New York

- 1984 “Patricia Johanson: Designs for Parks and Gardens,” Philippe Bonnafont Gallery, San Francisco

- 1983 “Patricia Johanson: Fair Park Lagoon, Dallas and Color-Gardens,” Rosa Esman Gallery, New York

- 1983 “Beyond the Monument,” M.I.T. and Harvard Graduate School of Design, Cambridge, Massachusetts

- 1982 “Patricia Johanson: A Project for the Fair Park Lagoon,” Dallas Museum of Fine Arts

- 1982 “Landshapes: A Living Lagoon,” Dallas Museum of Natural History

- 1981 “Patricia Johanson: Landscapes, 1969-1980, Rosa Esman Gallery, New York

- 1981 “Artist’s Parks and Gardens,” Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago

- 1980 “American Drawings in Black and White,” Brooklyn Museum, New York

- 1979 “Patricia Johanson: Drawings for the Camouflage House and Orchid Projects,” Rosa Esman Gallery, New York

- 1979 “Mind, Child, Architecture”, Newark Museum, New Jersey

- 1978 “Patricia Johanson: Plant Drawings for Projects,” Rosa Esman Gallery, New York

- 1978 “Celebration of Water,” Cooper-Hewitt Museum, Smithsonian Institution, New York

- 1977 “Women in American Architecture,” Brooklyn Museum, New York

- 1977 “The City Project: Outdoor Environmental Art,” New Gallery of Contemporary Art, Cleveland and Cleveland State University

- 1974 “Interventions in Landscape,” M.I.T., Cambridge, Massachusetts

- 1974 “Patricia Johanson: Some Approaches to Landscape, Architecture, and the City,” Montclair State College, New Jersey

- 1973 “Art in Space,” Detroit Institute of Arts

- 1973 “Patricia Johanson: A Selected Retrospective, 1959-1973,” Bennington College, Vermont

- 1968 “The Art of the Real”, Museum of Modern Art, New York; Grand Palais, Paris; Kunsthaus, Zurich; and Tate Gallery, London

- 1967 “Patricia Johanson: Paintings,” Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York

- 1966 “Distillation,” Stable Gallery and Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York

- 1964 “8 Young Artists,” Hudson River Museum, Yonkers and Bennington College, Vermont

Awards and Honors

- Guggenheim Fellowship, 1970

- Artist's Fellowship, National Endowment for the Arts, 1975

- International Women's Year Award, 1976

- Townsend Harris Medal, City College of New York, 1994

- D.F.A. (honorary), Massachusetts College of Art, Boston, 1995