Phaedrus (dialogue) facts for kids

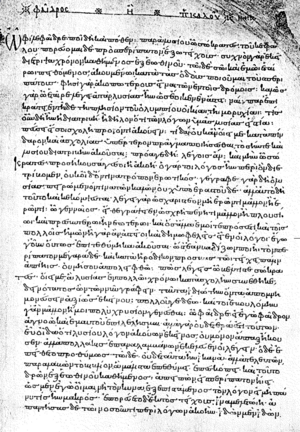

The Phaedrus is an ancient Greek book written by Plato. It's a conversation between two main characters: Socrates, a famous philosopher, and Phaedrus, a young man who likes speeches. This book was likely written around 370 BC, which is about the same time Plato wrote his other famous books, the Republic and the Symposium.

Even though the Phaedrus seems to be mostly about love, the characters also talk a lot about the art of rhetoric (which is the skill of speaking or writing to persuade people). They also discuss interesting ideas like metempsychosis (the Greek idea of reincarnation, where a soul is reborn into a new body) and what the human soul is like. A famous part of the book is the Chariot Allegory, which helps explain the nature of the soul.

Contents

Where the Story Happens

Socrates meets Phaedrus just outside the ancient city of Athens. Phaedrus has just left the home of a friend, where a famous speaker named Lysias gave a speech about love. Socrates, who loves listening to speeches, walks into the countryside with Phaedrus. He hopes Phaedrus will tell him all about the speech.

They find a nice spot by a stream under a plane tree and a chaste tree. They sit down, and the rest of the book is filled with their speeches and discussions. Unlike some of Plato's other works, this dialogue is told directly by Socrates and Phaedrus, without anyone else introducing the story.

Who Are the Characters?

- Socrates: A very famous Greek philosopher, known for asking many questions.

- Phaedrus: A young Athenian man who is interested in speeches and philosophy.

- Lysias: (He's not actually there, but his speech is discussed) Lysias was a well-known logographos, which means a "speech writer" in Athens during Plato's time. He wrote speeches for others to deliver in court or public gatherings.

Lysias was one of the sons of Cephalus, whose home is the setting for Plato's Republic. Lysias was a skilled speaker and writer.

Main Ideas of the Dialogue

The Phaedrus has three main speeches about love. These speeches then lead to a deeper discussion about how to use rhetoric properly. The dialogue also explores big ideas like the soul, different kinds of madness, divine inspiration, and how to become truly skilled at an art.

As they walk, Socrates tries to get Phaedrus to repeat Lysias' speech. Phaedrus makes excuses, but Socrates suspects Phaedrus has a copy. Socrates asks Phaedrus to show what he's hiding under his cloak. Phaedrus finally agrees to read Lysias' speech.

Lysias' Speech

Phaedrus and Socrates find a shady spot by the stream. Socrates jokes that he's not used to being in the countryside because he loves learning from "men in the town" more than from "trees and open country." He gives Phaedrus credit for leading him out of the city.

Phaedrus then reads Lysias' speech. The speech argues that it's better to be friends with someone who is not in love with you, rather than someone who is. Lysias says that friendship with a non-lover is more sensible and doesn't cause gossip. It also avoids jealousy and gives you more choices for friends. He explains that a non-lover is thinking clearly, unlike someone "overcome by love." Lysias concludes by saying his speech is long enough and invites questions.

Socrates pretends to be very impressed, but he's being a little sarcastic. He says the speech made Phaedrus "radiant" and that he must follow Phaedrus' lead. Phaedrus realizes Socrates is joking and asks him to stop. Socrates then claims he can give an even better speech than Lysias on the same topic.

Socrates' First Speech

Phaedrus begs Socrates to give his speech, but Socrates refuses at first. Phaedrus playfully warns him that he's younger and stronger and should "stop playing hard to get." Finally, after Phaedrus promises he'll never read another speech for Socrates if Socrates doesn't speak, Socrates agrees. He covers his head and begins.

Instead of just listing reasons like Lysias, Socrates starts by explaining that everyone desires beauty, but some people are in love and some are not. He says we are all guided by two main things: our natural desire for pleasure and our learned judgment that seeks what is best. Following your judgment means "being in your right mind." Following desire for pleasure without reason is "outrage" (hubris), which means extreme pride or disrespect.

Different desires lead to different behaviors. For example, someone who always follows their desire for food becomes a glutton. The strong desire for beauty, especially when it reminds us of beauty in human bodies, is called Eros (love).

Socrates then says he fears that the nymphs (nature spirits) will take over him if he continues, and he wants to leave before Phaedrus makes him "do something even worse."

However, just as Socrates is about to leave, he feels his "familiar divine sign," his daemon. This inner voice always stops Socrates just before he's about to do something wrong. A voice tells him not to leave until he makes up for offending the gods. Socrates admits that both speeches so far were bad. He says Lysias' speech repeated itself and seemed more interested in showing off than in the topic. Socrates realizes his mistake: if love is a god or something divine, as they both agree, then it cannot be bad, which is how the previous speeches described it. Socrates uncovers his head and promises to give a speech praising the lover.

Socrates' Second Speech

Understanding Madness

Socrates begins by talking about madness. He says that if madness were always bad, then the earlier speeches would be right. But actually, madness, when it's a gift from the gods, can bring us some of the best things. There are different kinds of divine madness (theia mania). For example, Apollo gives people prophetic madness (the ability to see the future), and Dionysus is linked to ritual madness.

To prove that the madness of love is a divine gift that helps both the lover and the beloved, Socrates decides to show its divine origin. He says this proof will convince "the wise if not the clever."

The Nature of the Soul

He starts by briefly explaining why the soul is immortal. A soul is always moving, and because it moves itself, it has no beginning. Something that moves itself is the source of all other movement. So, it cannot be destroyed. Things that are moved from the outside have no soul, but things that move from within have a soul. Since all souls move from within, they must be immortal.

Then comes the famous chariot allegory. Socrates says a soul is like a "team of winged horses and their charioteer." For the gods, both horses are good. But for everyone else, it's a mix: one horse is beautiful and good, while the other is not.

Because souls are immortal, those without bodies fly around heaven as long as their wings are perfect. When a soul loses its wings, it comes to Earth and takes on an earthly body that then seems to move itself. These wings lift heavy things up to where the gods live. They grow strong when they are near the wisdom, goodness, and beauty of the divine. But ugliness and badness make the wings shrink and disappear.

In heaven, Socrates explains, there's a procession led by Zeus, who takes care of everything. All the gods, except for Hestia, follow Zeus. The gods' chariots are balanced and easy to control. But other charioteers have to struggle with their bad horse, which will drag them down to Earth if it hasn't been trained well. As the procession moves upward, it eventually reaches the high edge of heaven. There, the gods stand and are carried in a circle to gaze at everything that is beyond heaven.

What is outside of heaven, Socrates says, is hard to describe. It has no color, shape, or solid form. It is the source of all true knowledge, and only intelligence can see it. The gods love these things and are nourished by them. Feeling wonderful, they go around in a full circle. On the way, they see Justice, Self-control, Knowledge, and other unchanging things as they truly are. After seeing and enjoying all these things, they return down into heaven.

The immortal souls that follow the gods most closely can just barely lift their chariots to the edge and glimpse this true reality. They see some things and miss others because they have to control their horses. They rise and fall at different times. Other souls try hard to keep up but can't rise. They leave in a noisy, sweaty mess, not having seen reality. Where they go next depends on their own ideas, not the truth. Any soul that sees even a little bit of true reality gets another chance to see more. Eventually, all souls fall back to Earth. Those who have seen more are born into different human lives. Philosophers have seen the most, followed by kings, statesmen, doctors, prophets, poets, workers, sophists (clever debaters), and tyrants.

Souls then begin cycles of reincarnation. It usually takes 10,000 years for a soul to grow its wings back and return to where it came from. But philosophers, after choosing such a life three times in a row, grow their wings and return after only 3,000 years. This is because they have seen the most and always remember it. Philosophers ignore everyday human worries and are drawn to the divine. Ordinary people might criticize them for this, but they don't realize that a lover of wisdom is inspired by a god. This is the fourth kind of madness: the madness of love.

The Madness of Love

This kind of love appears when someone sees beauty on Earth and is reminded of the true beauty they saw beyond heaven. When they remember, their wings start to grow back. But since they can't yet fly, they look up and ignore what's happening around them. This makes people think they are mad. Socrates says this is the best form of being possessed by a god, and it benefits everyone involved.

Talking About Rhetoric and Writing

After Phaedrus agrees that Socrates' speech was much better than Lysias', they start discussing the nature and uses of rhetoric itself. They agree that speaking or writing badly is shameful, but speaking or writing well is not. Socrates then asks what makes writing good or bad.

Phaedrus claims that to be a good speaker, you don't need to know the truth of what you're talking about, only how to persuade people. Socrates disagrees. He says a speaker who doesn't know good from bad will produce "a crop of really poor quality." Socrates believes that even if you know the truth, you might not convince anyone without knowing the art of persuasion. But he also says, "there is no genuine art of speaking without a grasp of the truth, and there never will be."

To learn the art of rhetoric, you need to be able to sort things into two groups: things that mean the same to everyone (like "iron" or "silver") and things that mean different things to different people (like "good" or "justice"). Lysias failed to do this, and he didn't even define "love" at the beginning of his speech. Because of this, the rest of his speech seemed randomly put together and poorly built. Socrates then says: "Every speech must be put together like a living creature, with a body of its own; it must be neither without head nor without legs; and it must have a middle and extremities that are fitting both to one another and to the whole work."

Socrates' speech, on the other hand, started with a main idea and then divided it into parts, finding divine love and showing it as the greatest good. They agree that the skill of making these divisions is called dialectic (the art of logical discussion), not rhetoric.

Socrates and Phaedrus then talk about the different parts of speeches that ancient speakers used. Socrates says that simply knowing these parts isn't enough. He compares it to a doctor who knows how to change a body's temperature but doesn't know when it's good or bad to do so. Someone who has just read a book about speaking knows nothing of the true art. He says that those who try to teach rhetoric only through "preambles" (introductions) and "recapitulations" (summaries) don't understand dialectic. They only teach the basic steps, not the true skill.

They then discuss what is good or bad in writing. Socrates tells a short story about the Egyptian god Theuth, who invented writing and gave it to King Thamus. Theuth thought writing would help people remember things. But Thamus replied that it would actually do the opposite: it would make people rely on writing to remind them, instead of truly remembering. He said future generations would hear a lot without being properly taught, and they would seem wise but not truly be so, making them difficult to get along with.

Socrates states that written instructions for an art can't give clear or certain results. They can only remind those who already understand what the writing is about. Also, writings are silent. They can't speak, answer questions, or defend themselves.

Therefore, the true "sister" of writing is dialectic. This is the living, breathing conversation of someone who truly knows, and written words are just an image of it. The person who truly knows uses the art of dialectic instead of just writing: "The dialectician chooses a proper soul and plants and sows within it discourse accompanied by knowledge—discourse capable of helping itself as well as the man who planted it, which is not barren but produces a seed from which more discourse grows in the character of others. Such discourse makes the seed forever immortal and renders the man who has it happy as any human being can be."

See also

In Spanish: Fedro para niños

In Spanish: Fedro para niños

- The Symposium

- The Republic

- The Gorgias

- Allegory of the cave

- Platonism

- Reincarnation

- Theory of Forms

- Divine Madness in Ancient Greece and Rome

Images for kids

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |