Picture bride facts for kids

The term picture bride describes a special way people got married in the early 1900s. It was mostly used by Japanese, Okinawan, and Korean workers living in Hawaii, the West Coast of the United States, and Canada. These workers chose their wives from their home countries using only photographs and family recommendations. A special helper, called a matchmaker, would pair up the bride and groom. This was a quicker version of traditional arranged marriages and is similar to what we now call a mail-order bride.

Contents

Why Men Wanted Picture Brides

In the late 1800s, many Japanese, Okinawan, and Korean men came to Hawaii. They worked hard on sugarcane plantations for low pay. Some of these men later moved to the mainland United States. At first, they planned to work for a few years and then go back home. For example, between 1886 and 1924, nearly 200,000 Japanese people came to Hawaii, but over 113,000 went back to Japan.

However, many men didn't earn enough money to return home. Also, in 1907, an agreement called the Gentlemen's Agreement of 1907 stopped laborers from moving from Hawaii to the mainland U.S. This meant many men had to stay in Hawaii or the U.S. mainland and make it their new home. Part of settling down was getting married. Plantation owners in Hawaii also wanted their workers to marry. They believed that having wives would make the men more likely to stay and settle down.

Why Women Became Picture Brides

Many things led women to become picture brides. Some came from poor families and saw it as a way to improve their lives financially. They hoped to find a better life in Hawaii or the United States. They also wanted to send money back to their families in Japan and Korea. Some of these women were quite educated, even having gone to high school or college. This made them brave enough to look for new chances abroad.

Other women felt they had to become picture brides because of their families. Their parents often helped arrange these marriages, and the daughters felt they couldn't say no to their parents' wishes. One former picture bride said, "I had only distant ties with him, but because our close parents talked and my parents approved, I decided on our picture-bride marriage." There is no sign that families sold their daughters to their husbands.

Some women also became picture brides to escape family duties. They thought leaving Japan or Korea would free them from responsibilities that came with traditional marriages. They hoped to gain more freedom than they had in their home countries. A Korean picture bride named Mrs. K explained, "Hawaii's a free place, everybody living well. Hawaii had freedom, so if you like talk, you can talk, if you like work, you can work." As more women became picture brides, some just followed the trend. One Japanese picture bride, Motome Yoshimura, said, "I wanted to come to the United States because everyone else was coming. So I joined the crowd."

How the Marriages Worked

These Japanese, Okinawan, and Korean women were called "picture brides" because the men in Hawaii and the U.S. mainland sent photos back home to find a wife. Family members, often with a helper called a nakodo (in Japanese) or a jungmae jaeng-i (in Korean), used these photos to find wives. When looking for possible brides, these helpers considered the woman's family background, health, age, and wealth.

The picture bride marriage process was based on traditional arranged marriage customs. In Japan, this was called miai kekkon, and in Korea, jungmae gyeolhon. The main difference was that in picture bride marriages, the man had no role in meeting the bride before the wedding. Once the bride's name was added to her husband's family record, the marriage was official in Japan. This allowed her to get travel papers for the U.S. However, the American government did not see these marriages as legal. So, large wedding ceremonies were held at the docks or in hotels after the brides arrived.

Coming to America

The Gentlemen's Agreement of 1907 stopped the Japanese government from giving passports to laborers who wanted to go to the U.S. mainland or Hawaii. But there was a way around this rule: wives and children were allowed to immigrate to join their husbands and fathers. This loophole allowed many picture brides to come to the United States.

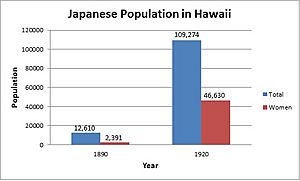

The impact of this agreement was clear in the number of men and women who came. Before the agreement, about 87% of Japanese people coming to the U.S. were men. After the agreement, only about 42% were men. By 1897, Japanese people were the largest ethnic group in Hawaii. By 1900, they made up 40% of the population. Between 1907 and 1923, over 14,000 Japanese picture brides and about 950 Korean picture brides arrived in Hawaii.

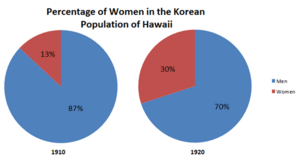

Similarly, Japan stopped Koreans from immigrating to Hawaii after Korea became a Japanese protectorate in 1905. But picture brides were an exception. Even though Korean laborers couldn't enter the U.S. from Hawaii after 1907, Korean picture brides started coming to the West Coast by 1910. In 1910, there were ten Korean men for every one woman in the United States. By 1924, the number of Korean women had grown, with about three men for every woman. This was because many Korean girls already in the U.S. reached marriage age, and between 950 and 1,066 brides arrived. From 1908 to 1920, over 10,000 picture brides came to the West Coast of the United States.

First Impressions in America

The journey for the picture brides was difficult. When they first arrived, they had to go through many checks at the immigration station. Since the U.S. government didn't see picture marriages as legal, the brides met their future husbands for the first time and then had a large wedding ceremony right at the docks.

Many women were surprised by what they found. Most of what they knew about their husbands came from the photos they had sent. However, these pictures didn't always show the men's real lives. Men would send photos that were old, touched up, or even pictures of different men entirely. They often wore borrowed suits and posed with fancy things like cars and houses that they didn't actually own.

One picture bride described how many brides felt after meeting their husbands: "I came to Hawaii and was so surprised and very disappointed, because my husband sent his twenty-five-year-old handsome-looking picture...He came to the pier, but I see he's really old, old-looking. He was forty-five years more old than I am. My heart stuck." On average, the husbands were 10 to 15 years older than their brides.

The age of their husbands wasn't the only shock. The women were also surprised by their living conditions. Many expected to live in nice houses like those in the photos. Instead, they found simple, isolated, and segregated plantation homes. One reason the grooms and matchmakers weren't completely honest was that they believed the women wouldn't come if they knew the truth about the men and their living situations.

Life in Hawaii

Even though they lived in Hawaii, Japanese picture brides wanted to keep their traditions and culture alive. They taught their children values like respecting elders, helping their community, working hard, saving money, and aiming for success. Many picture brides worked on the plantations. In 1920, 14% of plantation workers were women, and 80% of those women were Japanese. They usually watered fields, pulled weeds, or cut sugarcane. Men did similar jobs but were often paid more. For example, in 1915, Japanese women plantation workers earned 55 cents, while men earned 78 cents.

Besides working in the fields, the women also had to take care of their homes. This included cooking, cleaning, sewing, and raising children. If a woman couldn't afford childcare, she might work with her child on her back. Some picture brides with children left the fields to work for single men, doing laundry, cooking, or making clothes. Korean picture brides often left plantation life sooner than Japanese women. Many moved to Honolulu to start their own businesses. No matter where they lived, it was important for picture brides to build communities with each other through women's groups and churches.

Challenges of Picture Bride Marriages

Even if they were unhappy at first, most picture brides eventually settled into their marriages. They often accepted their situation to avoid shaming their families. Japanese couples often came from similar areas in Japan, so they had fewer marriage problems than Korean couples, who were often from different parts of Korea. However, not every marriage worked out. Some picture brides, after seeing their husbands for the first time, rejected them and went back to Japan or Korea.

Some wives who were unhappy with their husbands ran away with another man. This was very risky for picture brides because it could ruin their reputation and put their right to live in the United States in danger. Wives who ran away could be sent back to Japan. For these women, a group called the Women's Home Missionary Society in the U.S. provided temporary housing while they waited to go back to Japan. To find their missing wives, husbands would put ads in Japanese community newspapers, offering rewards for anyone who could find them.

Many people in the U.S. and Hawaii thought the Gentlemen's Agreement would stop Japanese immigration. So, when many picture brides started arriving, it restarted the Anti-Japanese Movement. People who were against Japanese immigration and picture brides were called "exclusionists." They called picture bride marriages uncivilized because they didn't involve love or morality. Exclusionists believed these marriages broke the Gentlemen's Agreement, thinking the women were more like workers than wives. They also worried that children from these marriages would be a problem because they could buy land for their parents in the future. Overall, there was a negative feeling toward picture brides in the United States.

The End of the Practice

To keep good relations with the United States, the Japanese government stopped giving passports to picture brides on March 1, 1920. This was because the brides were not well-received in the U.S. The end of the picture bride practice left about 24,000 single men with no way to return to Japan and bring back a wife. Despite this, picture brides and the Gentlemen's Agreement helped create a second generation of Japanese Americans, called Nisei. By 1920, there were 30,000 Nisei people.

Picture Brides in Books and Movies

- Yoshiko Uchida's novel, Picture Bride (1987), tells the story of a Japanese woman named Hana Omiya. She is a picture bride sent to live with her new husband in Oakland, California in 1917. The book also shows her experiences in a Japanese internment camp in 1943.

- The movie Picture Bride (1994) was made by Hawaii-born director Kayo Hatta. It stars Youki Kudoh and tells the story of Riyo, a Japanese woman whose photo exchange with a plantation worker brings her to Hawaii. This movie is not related to Uchida's novel.

- The Korean book Sajin Sinbu (2003), which means "Picture Bride," was put together by Park Nam Soo. It looks at the picture bride story from a Korean and Korean-American point of view. It includes history, poems, short stories, and essays by various Korean authors. The book was made for the Korean Centennial, marking 100 years since the first known Korean immigrants arrived in the U.S. in 1903.

- Alan Brennert's novel, Honolulu (2009), features a Korean picture bride who comes to Hawaii.

- Julie Otsuka's novel, The Buddha in the Attic (2011), describes the lives of picture brides who came from Japan to San Francisco about a century ago. It also explores what it means to be an American during uncertain times. The novel was a finalist for the National Book Award for fiction in 2011.

- The final episode of the AMC TV series, The Terror: Infamy (2019), shows that Yūko was a picture bride before she became a yūrei.

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |