Pigouvian tax facts for kids

A Pigouvian tax (pronounced Pig-OO-vee-an tax) is a special kind of tax that a government puts on activities that cause harm to others. This harm is called a "negative externality". It means that the cost of something isn't fully paid by the person or company doing it.

For example, if a factory pollutes the air, the cost of that pollution (like health problems for people nearby) isn't included in the price of what the factory makes. A Pigouvian tax tries to fix this. It makes the factory pay for the harm it causes. This encourages the factory to pollute less.

These taxes are named after Arthur Cecil Pigou, a British economist (1877–1959). He came up with the idea of externalities. Sometimes, the opposite happens: an activity creates good things for others that aren't paid for. In these cases, a "Pigouvian subsidy" might be given. This helps people pay for good things, like flu vaccines, to encourage more people to get them.

Contents

Why We Need Pigouvian Taxes

In 1920, Arthur Cecil Pigou wrote a book called The Economics of Welfare. He explained that businesses usually only care about their own costs and profits. But sometimes, their actions affect society in ways they don't pay for.

For instance, if a company builds a factory in a busy neighborhood, it can cause problems. These problems might include more traffic, less sunlight for homes, and even health issues for neighbors. Pigou called these "incidental uncharged disservices."

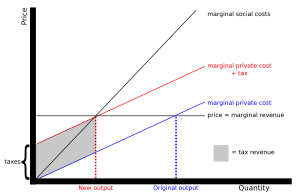

When a company doesn't pay for the harm it causes, it might produce too much of something. This is because the true cost to society is higher than the cost to the company. A Pigouvian tax aims to make the company pay for these hidden costs. This helps reduce the amount of harmful activity, bringing things back to a better balance.

How a Pigouvian Tax Works

Imagine a factory that pollutes. A Pigouvian tax adds a cost to each unit of pollution the factory creates. This makes it more expensive for the factory to pollute.

When the tax is added, the factory has a reason to produce less pollution. It might reduce how much it makes. Or, it might invest in cleaner ways to produce its goods. The goal is to make the factory's costs include the harm it causes to others. This helps the economy reach a point where the amount of pollution is at a healthy level for everyone.

Other Ways to Deal with Pollution

Pigouvian taxes are one way governments try to fix problems caused by negative externalities. They are often used because they are fairly simple to put into action. However, there are other ideas too.

Talking It Out Directly

Economist Ronald Coase suggested that sometimes people can solve problems themselves. If the costs of talking and agreeing are low, neighbors might work out issues like noise or smoke without the government. For example, two neighbors could agree on how to share a fence. This might be easier than asking a third party to decide.

Setting Limits for Companies

Instead of taxing pollution, the government could set limits. For example, it could say how much pollution each factory is allowed to produce. This is called "command and control regulation." If all factories have to reduce their pollution, it can make the products they sell more expensive. This might encourage companies to find cleaner ways to produce.

Cap and Trade Systems

Another idea is called "cap and trade." Here, the government sets a total limit (a "cap") on how much pollution can be created. Then, it gives out or sells "permits" to companies. Each permit allows a company to pollute a certain amount.

Companies can then buy and sell these permits among themselves. If a company pollutes less, it can sell its extra permits to another company that needs to pollute more. This creates a market for pollution rights. It gives companies a reason to pollute less, because they can earn money by selling their permits.

Examples of Pigouvian Taxes

You might see Pigouvian taxes in action in many places:

- Environmental taxes: These include carbon taxes on fuels that cause climate change.

- Fuel taxes: Taxes on gasoline can help pay for road damage and reduce traffic.

- Taxes on congestion: These are taxes for driving in busy city areas to reduce traffic jams.

- Plastic taxes: Taxes on plastic bags or other plastic items to reduce waste.

- Fat taxes and sugar taxes: These are taxes on unhealthy foods and drinks. They aim to reduce health problems like obesity.

- Tobacco taxes: Taxes on cigarettes help cover public healthcare costs and discourage smoking.

- Sin taxes: A general term for taxes on things considered harmful, like tobacco or alcohol.

- Chewing gum tax: Some places tax chewing gum to help pay for cleaning up gum litter.

Challenges with Pigouvian Taxes

Even though Pigouvian taxes sound good, they have some challenges.

How to Measure the Harm?

One big problem is figuring out the exact cost of the harm. How do you put a money value on air pollution or noise? It's very hard to measure the "social cost" of an externality. This is because many costs, like how pollution affects someone's mood, are personal and hard to count.

Because it's tough to know the exact harm, it's also hard to set the perfect tax level. Some economists suggest that instead of finding the perfect tax, we should just set a minimum acceptable standard for pollution. Then, we can create taxes to meet those standards.

Fairness and Reciprocity

Ronald Coase also pointed out that harm is often "reciprocal." This means both sides play a part. For example, a factory makes smoke, but people also choose to live near the factory. If people weren't there, the smoke wouldn't harm anyone. Because of this, Coase argued that neither side is fully responsible. So, neither side should pay the full cost alone.

He also said that if a tax makes a factory clean up its act, more people might move nearby. This could then make the "social cost" of any remaining pollution seem higher, leading to calls for an even higher tax. This could unfairly punish the factory for making things better.

Political Issues

Politics can also make Pigouvian taxes tricky. Companies that pollute might try to influence the government to set lower taxes. On the other hand, groups worried about pollution might push for taxes that are too high.

Sometimes, politicians might choose taxes based on what brings in the most money for the government, not just what's best for the environment. For example, a tax might be put on the makers of a chemical, even if the real problem comes from how people use that chemical. This happens if it's easier to tax a few manufacturers than many individual users.

Also, politicians sometimes prefer rules that have clear benefits but hidden costs. For example, giving out free pollution permits to companies might seem good because it doesn't look like a tax. But it can still make products more expensive for consumers. A direct tax might be more efficient, but it's often less popular with businesses.

See also

In Spanish: Impuesto pigouviano para niños

In Spanish: Impuesto pigouviano para niños

- Carbon trading

- Coase theorem

- Environmental tax

- Polluter pays principle

- Sin tax

- Soda tax

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |