Turtle shell facts for kids

The turtle shell is like a strong shield that protects turtles. It covers their back and belly, keeping all their important body parts safe. In some turtles, the shell can even cover their head! This amazing shell is made from special bones, including their ribs and parts of their pelvis. It's built from both regular bones and special skin bones, which means the shell likely grew by adding armor from the skin to the rib cage.

A turtle's shell is super important for several reasons. Not only does it protect the turtle, but it also helps scientists identify different types of turtles, especially from fossils. Since shells are very strong, they often survive for millions of years. By understanding how shells are built in living turtles, scientists can learn more about ancient turtles too.

Did you know that the shell of some turtles, like the hawksbill turtle, has been used for making beautiful items for a very long time? People often call this material "tortoiseshell."

Contents

Parts of a Turtle Shell

A turtle's shell has many different parts, both bony and made of a tough material called keratin. Think of keratin like your fingernails! The top part of the shell, which covers the turtle's back, is called the carapace. The bottom part, which covers its belly, is called the plastron. These two parts are connected by an area called the bridge.

Inside the shell, there's a thin layer of skin called the epidermis. This layer makes the shell even stronger. Even though it's very thin, it helps the shell bend a little without breaking and gives it more support. This skin layer is thicker in important areas, allowing the shell to handle more pressure without getting damaged.

The shape of a turtle's shell has changed over millions of years through evolution. This shape helps turtles survive and move around. For example, some shell shapes help turtles escape from predators. The shell also has tiny structures, like the scutes (the plates on the outside) and ribs inside, that add extra strength. These ribs also allow the shell to flex a bit, which is helpful when a turtle needs to move quickly or escape danger. Some turtles even have a thin layer of mucus on their shell, which helps them move through water more easily by reducing friction.

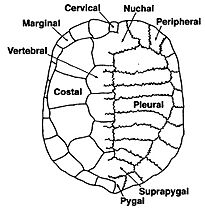

The bones of the shell are named after similar bones in other animals. The carapace has eight "pleural" bones on each side, which are a mix of ribs and skin bones. At the front is a single "nuchal" bone, and along the sides are twelve pairs of "peripheral" bones. At the back, there's a "pygal" bone and a "suprapygal" bone.

Between the pleural bones are "neural" bones, which protect the spinal cord. Some turtles also have extra bones called "mesoplastra" in the bridge area.

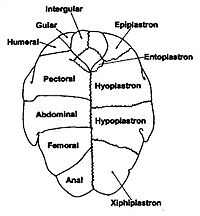

The plastron (bottom shell) also has many bones, mostly in pairs. At the front are two "epiplastra," followed by "hyoplastra." These bones surround a single "entoplastron." The back half of the plastron has two "hypoplastra" and two "xiphiplastra" at the very rear.

On top of these bones are the scutes, which are made of tough keratin. On the carapace, there are five "vertebral" scutes down the middle, four pairs of "costal" scutes on the sides, and twelve pairs of "marginal" scutes around the edge. These scutes are arranged so that their seams don't line up with the bone seams underneath, which makes the shell even stronger. Some turtles have a "cervical" scute at the front of the carapace, but not all do.

On the plastron, there are two "gular" scutes at the front, then "pectorals," "abdominals," "femorals," and "anals." Some turtles, called Pleurodires, have an extra "intergular" scute between the gulars, giving them 13 scutes on their plastron. Other turtles, called Cryptodires, usually have 12.

The Carapace: Top Shell

The carapace is the rounded, top part of a turtle's shell. It's formed when the turtle's ribs and spine grow and fuse together with special bones from its skin. On the outside, the carapace is covered by horny plates called scutes, which are made of keratin. These scutes protect the shell from scratches and bumps. Some turtles have a ridge, called a "keel," running down their back.

Most turtle shells look pretty similar in their basic structure, with differences mainly in shape and color. However, some turtles, like soft-shell turtles and leatherback sea turtles, have lost their scutes and have less bone in their shells. Their shells are covered only by skin. These turtles usually live mostly in water.

The way a turtle's carapace evolved is very special. Unlike other animals where shoulder blades are outside the ribcage, a turtle's shoulder blades are inside its ribcage! Also, in most animals, the ribs can move freely. But in turtles, the ribs are fused to the shell, which means they can't move much. Scientists learned from an ancient fossil called Eunotosaurus africanus that early turtle ancestors lost the muscles between their ribs, which allowed their ribs to become part of the shell.

The Plastron: Belly Shell

The plastron is the flatter, bottom part of a turtle's shell, covering its belly. It includes the bridge that connects it to the carapace. The plastron is made of nine bones. Scientists believe some of these bones are similar to the collarbones in other animals, while others are like special belly ribs.

How the plastron evolved has been a bit of a mystery. Some scientists thought it grew from the turtle's breastbone. While turtles don't have a typical breastbone, their body plan uses similar bone material to form the plastron. This suggests that the plastron might have evolved from floating belly ribs. Over time, the ribs became specialized for supporting the body, and the belly muscles became specialized for breathing. These changes happened millions of years before the shell was fully formed.

A fossil of an ancient turtle ancestor called Pappochelys rosinae gave scientists more clues. Pappochelys had paired belly ribs that showed signs of once being fused together. This suggests that over time, these separate belly ribs gradually fused to form the solid plastron we see in modern turtles.

In some turtle species, the plastron has a hinge! This allows the turtle to close its shell almost completely, protecting itself even more. Also, in some species, you can tell if a turtle is male or female by looking at its plastron. Males often have a slightly curved-in (concave) plastron, while females have a flatter or slightly curved-out (convex) one.

The scutes on the plastron meet along a central line. The length of these scute sections can help identify different turtle species. There are six pairs of scutes on the plastron, from head to tail: gular, humeral, pectoral, abdominal, femoral, and anal.

The gular scute is the very front part of the plastron. Some tortoises have two gular scutes, while others have just one. If they stick out like a small shovel, they might be called a "gular projection."

Plastron Scute Lengths

Scientists use a "plastral formula" to compare the lengths of the scutes on the plastron. They use abbreviations for each scute:

- intergular (intergul)

- gular (gul)

- humeral (hum)

- pectoral (pect)

- abdominal (abd)

- femoral (fem)

- anal (an)

For example, for the eastern box turtle, the formula is: an > abd > gul > pect > hum >< fem. This means the anal scute is longer than the abdominal, and so on.

Ancient Chinese people used turtle plastrons for a type of fortune-telling called plastromancy.

Scutes: The Outer Plates

The turtle's shell is covered by scutes, which are made of keratin, the same material as your fingernails and hair. Each scute has a specific name and is usually found in the same place on most turtle species.

Land tortoises do not shed their scutes. Instead, new layers of keratin are added to the bottom of each scute, making them grow. However, aquatic turtles often shed their individual scutes. The scutes act like the "skin" over the bones of the shell, with a very thin layer of tissue in between.

Scutes can be brightly colored in some species! Often, the top of the shell (carapace) is darker than the bottom (plastron). This helps turtles blend in with their surroundings. Scientists have found that the patterns on the plastron scutes develop separately from the patterns on the carapace scutes, suggesting that the top and bottom parts of the shell evolved at different times.

The appearance of scutes is linked to when animals moved from living in water to living on land, about 340 million years ago. As amphibians evolved into land animals, their skin changed a lot. Early ancestors of turtles likely developed a tough, horny skin covering as they adapted to life on land.

| Zangerl 1969 | Carr 1952 | Boulenger 1889 | Pritchard 1979 |

|---|---|---|---|

| cervical | precentral | nuchal | nuchal |

| vertebral | central | vertebral | central |

| pleural | lateral | costal | costal |

| marginal | marginal | marginal | marginal |

| 12th marginal | postcentral | supracaudal | supracaudal |

| intergular | - | intergular | intergular |

| gular | gular | (extra-) gular | gular |

| humeral | humeral | humeral | humeral |

| pectoral | pectoral | pectoral | pectoral |

| abdominal | abdominal | abdominal | abdominal |

| femoral | femoral | femoral | femoral |

| anal | anal | anal | anal |

How the Shell Develops

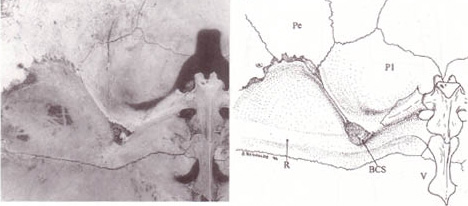

A special part called the "carapacial ridge" is key to how a turtle's shell forms. In a developing turtle embryo, this ridge helps the ribs grow sideways instead of downwards. These sideways-growing ribs then connect to the skin on the back, helping the carapace (top shell) to form. This process also causes the shoulder bones to move inside the rib cage, which is unique to turtles.

Scientists study genes like PAX1 and Sonic hedgehog gene (Shh) to understand how the shell develops. These genes control how the backbone forms and how the ribs grow to create the shell.

How the Shell Evolved

Scientists have different ideas about how the turtle's unique shell came to be.

The "Polka Dot Ancestor" Idea

One idea is that bony plates in the skin, called osteoderms, first fused together and then attached to the ribs underneath. This idea suggests a hypothetical ancestor that had a back covered in these bony plates, like a "Polka Dot Ancestor." This theory tried to explain how some ancient reptiles evolved, but it didn't fully explain how the ribs became attached to these skin plates.

The Broadened Ribs Idea

More recent fossil discoveries have given scientists a clearer picture of how the turtle shell evolved.

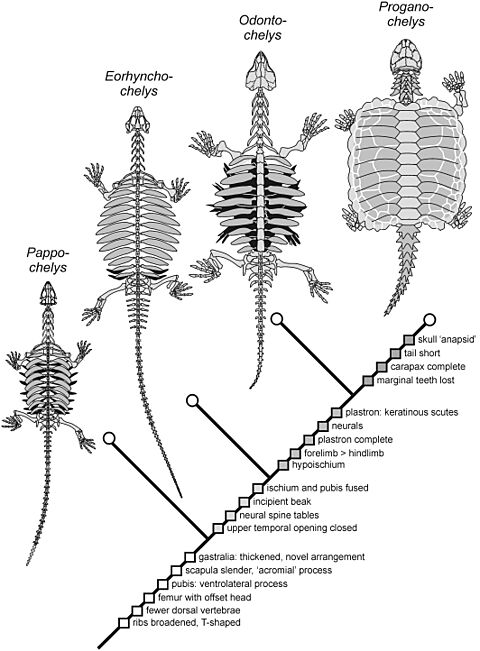

Early Turtle Ancestors

About 260 million years ago, during the Permian period, a fossil called Eunotosaurus was found in South Africa. This animal had a short, wide body with ribs that were broad and slightly overlapped. This suggests it was an early step in getting a shell. Some scientists think Eunotosaurus might have lived underground, like a gopher tortoise. Its strong shoulders and shovel-like hands would have been great for burrowing. Living underground might have helped Eunotosaurus survive a huge extinction event at the end of the Permian period, playing a big role in the early evolution of shelled turtles.

Full Shell Evolution

Later, about 240 million years ago in Germany, another fossil called Pappochelys was found. It had even more distinctly broadened ribs.

Then, about 220 million years ago in China, a fossil called Odontochelys semitestacea was discovered. This ancient turtle had a complete plastron (bottom shell) but only a partial carapace (top shell). This fossil showed that the plastron evolved before the carapace! Like modern turtles, it didn't have muscles between its ribs, so its ribs couldn't move much.

Finally, the shell became fully complete with the fossil of Proganochelys, found in Germany and Thailand. This turtle lived about 220 million years ago. It couldn't pull its head into its shell, and it had a long neck and a spiky tail with a club at the end, a bit like an ankylosaur dinosaur.

Shell Problems

Shell Rot

"Shell rot" is a disease that causes sores on a turtle's shell. It happens when bacteria or fungi get into a scratch or injury on the shell. It can also be caused by poor living conditions for the turtle. If not treated, the infection can spread to other organs.

Pyramiding

Pyramiding is a shell problem seen in pet tortoises. It makes the shell grow unevenly, creating pyramid shapes under each scute. This can happen if a tortoise doesn't get enough water, eats too much protein, or doesn't get enough calcium, UVB light, or vitamin D3.

Some studies show that dry conditions during a young tortoise's growth can cause pyramiding. For example, researchers found that young African spurred tortoises raised in dry conditions developed taller humps than those raised in humid conditions, even if their diet was the same.

-

The bottom shell (plastron) of a wild male Hermann's tortoise with shell rot (red circle) and old scars (black circles).

-

A gopher tortoise with severe pyramiding on its shell.

|