Igneous intrusion facts for kids

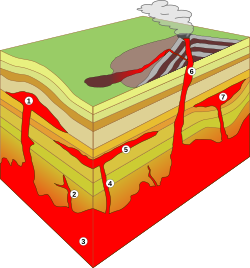

In geology, an igneous intrusion is a body of igneous rock that forms when magma (melted rock) cools and hardens slowly beneath the Earth's surface. Think of it like a giant blob of melted rock pushing its way into existing rocks underground and then solidifying. These intrusions come in many different shapes and sizes. Some famous examples include the Palisades Sill in New York and New Jersey, and Shiprock in New Mexico.

Because the surrounding country rock (the rock already there) acts like a good blanket, the magma cools very, very slowly. This slow cooling allows large mineral crystals to grow, making the intrusive igneous rock look coarse-grained (you can see the crystals easily). Scientists classify these rocks based on the types and amounts of minerals they contain.

One big question for geologists is how these huge bodies of magma make space for themselves in the solid rock. This is called the room problem, and scientists are still studying it!

The word pluton is often used to describe a large igneous intrusion that formed deep underground. Sometimes it's used for any igneous intrusion, or for a very big one, or even for a solidified magma chamber.

Types of Igneous Intrusions

Igneous intrusions are generally divided into two main types:

- Discordant intrusions cut across the layers or structures of the existing country rock.

- Concordant intrusions push their way in parallel to the existing layers of rock.

Scientists further classify them by their size, how they formed, or if they are flat and sheet-like. An intrusive suite is a group of intrusions that are related in time and space.

Discordant Intrusions

These intrusions cut across the older rock layers.

Dikes: Rock Walls

Dikes are flat, sheet-like intrusions that cut across existing rock layers. They often stand out like natural walls in the landscape because they are harder than the surrounding rock and resist erosion. Dikes can be very thin, like a millimeter, or super thick, more than 300 meters (980 feet) wide! They form when magma pushes into cracks in the rock, especially where the Earth's crust is pulling apart.

Ring Dikes and Cone Sheets

These are special types of dikes that form in circles or cones. They are often found around calderas, which are large volcanic craters that form when a volcano collapses.

Volcanic Necks: Old Volcano Pipes

A volcanic neck is what's left of the magma pipe that fed an ancient volcano. Over time, the softer outer parts of the volcano erode away, leaving behind the hard, solidified magma pipe. These often look like tall, cylindrical rock formations.

Stocks: Smaller Intrusions

A stock is a type of discordant intrusion that covers less than 100 square kilometers (39 square miles) at the surface. Even though it might be just the top of a larger body, stocks have unique features that help geologists understand how they formed.

Batholiths: Giant Magma Bodies

Batholiths are huge discordant intrusions, covering more than 100 square kilometers (39 square miles). Some are truly enormous, like the Coastal Batholith of Peru, which is 1,100 kilometers (680 miles) long and 50 kilometers (31 miles) wide! They usually form from magma rich in silica, a common mineral, and are rarely made of dark, heavy rocks like gabbro.

Concordant Intrusions

These intrusions push their way in parallel to the existing rock layers.

Sills: Flat Sheets

A sill is a flat, sheet-like intrusion that lies parallel to the layers of sedimentary rock. They are similar to dikes but don't cut across layers. Most sills are made of mafic magma, which is low in silica and flows easily, allowing it to spread out between rock beds.

Laccoliths: Domed Intrusions

A laccolith is a concordant intrusion with a flat bottom and a domed, mushroom-shaped top. They usually form closer to the surface, less than 3 kilometers (1.9 miles) deep, especially where the Earth's crust is being squeezed.

Lopoliths: Saucer Shapes

Lopoliths are concordant intrusions that have a saucer shape, like an upside-down laccolith. They can be much larger than laccoliths and form through different processes. Their huge size means they cool very slowly, which can lead to layers of different minerals forming within the rock.

How Intrusions Form

Making Room for Magma

Magma forms when rocks deep inside the Earth melt. This melted rock is lighter than the solid rock around it, so it naturally wants to rise. But how does a huge amount of magma push aside solid rock to make space for itself? This is the "room problem" that geologists study.

The type of magma and the pressure on the surrounding rock greatly affect how intrusions form. For example, if the Earth's crust is stretching, magma can easily fill cracks to form dikes. If the crust is being squeezed, magma closer to the surface might form laccoliths, pushing into weaker rock layers.

Multiple Magma Injections

Large igneous intrusions often don't form from just one big blob of magma. Instead, they usually grow from many smaller injections of magma over time. For example, the famous Palisades Sill was formed from several magma injections, not just one giant pour. If the magma injections are all similar, it's called a multiple intrusion. If they are different types of magma, it's called a composite intrusion.

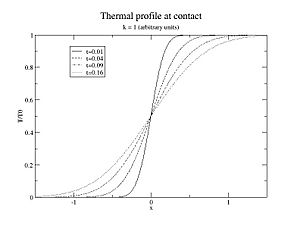

How Intrusions Cool

When hot magma pushes into cooler country rock, it loses heat to the surroundings. The magma closest to the country rock cools very quickly, forming a chilled margin that is finer-grained than the rest of the intrusion. The country rock closest to the magma also heats up, creating a contact aureole.

The further you go from the edge of the intrusion, the slower the magma cools. This means that thin dikes cool much faster than huge batholiths. This is why small intrusions near the surface often have very fine grains, almost like volcanic rock.

The way the intrusion meets the country rock can tell scientists about how deep it formed.

- Intrusions formed very deep often have a wide zone where the intrusion and country rock mix, showing a lot of chemical reaction.

- Intrusions formed at medium depths have clearer boundaries between the intrusion and the country rock.

- Intrusions formed close to the surface have very sharp boundaries, often with pieces of the country rock broken off and trapped inside the intrusion. These are common near volcanoes.

Cumulate Layers

As magma cools, different minerals crystallize at different temperatures. The first crystals to form are often heavier than the remaining magma, so they can sink to the bottom of a large intrusion. This creates special layers called cumulate layers, which have unique textures and compositions. These layers can sometimes contain valuable mineral deposits, like the chromite found in the huge Bushveld Igneous Complex in South Africa.

See also

In Spanish: Intrusión (geología) para niños

In Spanish: Intrusión (geología) para niños

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |