Princess Pauline of Anhalt-Bernburg facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Princess Pauline |

|

|---|---|

Portrait by Johann Christoph Rincklake, 1801

|

|

| Princess consort of Lippe | |

| Tenure | 2 January 1796 – 5 November 1802 |

| Regent of Lippe | |

| Tenure | 5 November 1802 – 3 July 1820 |

| Born | 23 February 1769 Ballenstedt |

| Died | 29 December 1820 (aged 51) Detmold |

| Burial | Detmold Mausoleum |

| Spouse |

Leopold I, Prince of Lippe

(m. 1796; died 1802) |

| Issue | Leopold II Prince Frederick Princess Louise |

| House | Ascania |

| Father | Frederick Albert, Prince of Anhalt-Bernburg |

| Mother | Louise Albertine of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Plön |

| Religion | Calvinism |

Pauline Christine Wilhelmine of Anhalt-Bernburg (born February 23, 1769 – died December 29, 1820) was an important ruler in a small German state called Lippe. She was also known as Princess Pauline of Lippe.

Pauline became a princess consort (the wife of a ruling prince) when she married Leopold I, Prince of Lippe in 1796. After her husband passed away in 1802, she became the regent (a temporary ruler) for her young son, Leopold II. She ruled Lippe for nearly two decades, until 1820.

Princess Pauline is remembered for many important changes. On January 1, 1809, she ended serfdom in Lippe. This meant that people who were tied to the land and had to work for a landlord were now free. She also worked hard to keep Lippe independent during the Napoleonic Wars, a time when many small states were taken over by larger powers.

Pauline was also very interested in helping people. She was inspired by new ideas from France and started some of the first social programs in Germany. These included the first day care center, a school for children who needed help, a work camp for adults who received charity, and a health center.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Pauline was born in Ballenstedt, a town in Germany. Her father was Prince Frederick Albert, Prince of Anhalt-Bernburg, and her mother was Louise Albertine of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Plön. Sadly, Pauline's mother died from measles just a few days after she was born.

Pauline had an older brother named Alexius Frederick Christian. Even when she was very young, people noticed that Pauline was very smart. Her father personally taught her and her brother. She was an excellent student and learned French, Latin, history, and political science. By the age of 13, she was already helping her father with government work. She handled letters in French and later managed all the communication between their home and the government offices. Her education was shaped by strong moral values and the ideas of the Age of Enlightenment, which focused on reason and individual rights.

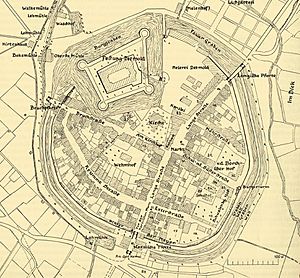

On January 2, 1796, Princess Pauline married Prince Leopold I, Prince of Lippe. The wedding was in Ballenstedt, and when they arrived in Detmold (the capital of Lippe), people cheered loudly. Leopold had wanted to marry Pauline for years, but she had said no many times. She only agreed after his health improved. Pauline later wrote that she was happy in her marriage and that her husband was "good, noble, and righteous."

Pauline and Leopold had two sons: Leopold (born in 1796) and Frederick (born in 1797). They also had a daughter named Louise, who sadly died very soon after she was born in 1800.

Becoming a Regent

Prince Leopold I died on April 4, 1802. On May 18, Pauline officially became the regent for her young son, Leopold II. According to their marriage agreement, Pauline was supposed to be the guardian and regent if her son became prince while still a child.

However, the Estates of Lippe (representatives of the nobility and cities) strongly disagreed with this rule. But there was no other suitable male guardian available, and Pauline had already shown she was capable of ruling. So, she became regent. Her time as ruler lasted for almost 20 years and is seen as a very good period in Lippe's history.

Pauline also served as the Mayor of Lemgo from 1818 until her death in 1820, even while she was still ruling Lippe. Lemgo was in debt after the Napoleonic Wars. The city asked Pauline to take charge of their police and money matters for six years, and she surprisingly accepted. She worked to improve the city's money and social situation, even though some of her decisions were unpopular. She started a workhouse for the poor and a service club there, just like she had done in Detmold.

Pauline had planned to move to the Lippehof, a palace in Lemgo, after she handed over the government to her son Leopold II on July 3, 1820. But she died on December 29, 1820, just a few months later, in Detmold. She was buried in the Church of the Redeemer in Detmold.

Pauline's Leadership Style

Pauline was known for being very strong-willed and direct. She wasn't afraid to speak her mind, even if it caused arguments. People who knew her described her as very intelligent and a powerful leader. One historian called her "one of the cleverest women of her time."

Pauline was very strict with her two sons, especially Leopold, who would become the next prince. She chose their teachers carefully. However, she admitted that she was sometimes too impatient with them, which led to difficult moments.

Before Pauline's rule, the ruler and the Estates (representatives of the nobles and cities) usually worked together to make decisions. But Pauline was used to a style of rule where the Prince made the final decisions, like in her home state. She didn't want the Estates to stop her from carrying out her good ideas for social help. She truly believed she knew what was best for Lippe and its people. For example, in 1805, the Estates said no to her plan for a tax on alcohol to pay for a hospital for people with mental illness. After that, she rarely called the Estates together and mostly made decisions on her own.

Pauline often attended government meetings and made her decisions there. She was especially focused on foreign policy because she spoke and wrote French better than any of her officials. It was very unusual for a woman to be so active in government back then, but her royal status allowed it. She took charge of the foreign ministry in 1810. In 1817, she also took over the management of the "madhouse" (as it was called then), a house for correcting behavior, and the distribution of aid to the poor.

Helping Her People: Social Policies

Pauline was very interested in helping the poor. She believed that poverty was often caused by a lack of education and a tendency for people to be "lazy." She thought that real improvement would come from people working, not just from receiving money.

She continued the work started by her late stepmother-in-law, Casimire of Anhalt-Dessau. Pauline founded several important institutions:

- A vocational school (1799) to teach practical skills.

- A day care center (1802) for young children.

- A hospital (1801–1802).

- A voluntary workhouse (1802) for the poor.

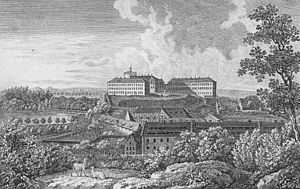

An orphanage already existed since 1720, and a teacher training college since 1781. Pauline brought these six institutions together, calling them "nursing homes," and housed them in a former convent. This was the beginning of what is now the Princess Pauline Foundation in Detmold. These "nursing homes" aimed to help people "from the cradle to the grave." They were considered very special and were visited by many people from other countries, especially the day care center. However, these services were only for people living in Detmold.

People liked Pauline mainly because of her social programs. These charitable institutions were seen as a model both in Lippe and abroad. She also helped during a time of famine from 1802 to 1804 by creating places to store grain. She personally worked to lessen the impact of military activities, like when soldiers needed places to stay.

Pauline also improved the country's infrastructure. She built new roads and introduced street lighting in Detmold, using 26 oil lamps. She also started the process of combining several book collections into a public library in 1819. Today's Lippe State Library at Detmold grew directly from this library.

Vocational School for Children

In 1798, Pauline began focusing on social issues. There was a lot of poverty in Lippe, and Pauline believed it was partly because people weren't educated enough. Many parents couldn't send their children to school because they needed them to work or beg to earn money.

Pauline's advisor, Simon Ernst Moritz Krücke, suggested starting a vocational school. Children would learn both school subjects and practical skills. The school opened in the orphanage in Detmold. Krücke taught poor children alongside the orphans. The school was officially opened on June 28, 1799. Children learned skills like knitting. Pauline visited the classes and gave small rewards. The knitted items were sold, and the children received some of the money. This helped convince parents to send their children to school instead of begging.

Germany's First Day Care Center

Pauline was concerned about young children whose parents had to leave them alone to work. She read in a Paris newspaper about a similar idea started by Joséphine de Beauharnais, the wife of Napoleon Bonaparte. In Paris, only single mothers could use the center, but Pauline wanted to help married couples too, if both parents worked.

Pauline wrote a letter to the ladies of Detmold, asking them to help supervise the center for free one day a week. The royal family would pay for the center. Older girls from the vocational school and orphanage would also help care for the children and learn how to look after them. In 1801, Pauline bought a building for the institution, and the first day care center opened on July 1, 1802. It cared for up to 20 children in its early years. Children had to be old enough to no longer need breastfeeding and no older than four years. The center was open from June to October, during the harvest and garden work season.

Pauline mostly paid for the center herself, with some money from the hospital fund. She also found twelve wealthy women to act as supervisors. They kept journals so Pauline could always know what was happening. The day care center was soon copied in other parts of Germany.

Pauline and Napoleon

Pauline admired Napoleon Bonaparte and was thankful that he allowed Lippe to remain independent. She believed Napoleon would win the wars he was fighting, even after his defeat in Russia. She did not want Lippe to leave the Confederation of the Rhine, an alliance of German states under Napoleon's influence. She even punished soldiers from Lippe who left Napoleon's army.

Once, a Prussian officer behaved badly towards her, and she had him locked up in the "madhouse." He was only released when Prussian troops occupied Lippe after Napoleon's defeat at the Battle of Leipzig. A Prussian commander described Pauline as a "rascal" who had "always served Napoleon faithfully."

Keeping Lippe Independent

One of Pauline's biggest successes was keeping Lippe independent. As regent, she felt it was her duty to protect her son's rights and the country's freedom. Lippe was a small state caught between powerful countries like France, Prussia, and Hesse.

In 1806, Napoleon created the Confederation of the Rhine. Pauline saw that Lippe's independence was at risk and decided to join this Confederation. Napoleon confirmed Lippe's membership in 1807. Pauline even traveled to Paris to negotiate special arrangements for Lippe. She believed it was better to be under the distant rule of France than to be taken over by closer neighbors like Hesse or Prussia.

Joining the Confederation meant Lippe had to provide soldiers for Napoleon's army. The people of Lippe resisted, and there were riots. Many young men avoided joining the army or ran away during the French wars. After Napoleon's defeat in October 1813 at the Battle of Leipzig, the people of Lippe attacked French officials, which upset Pauline because she still believed Napoleon would win.

Lippe was then occupied by Prussian troops, who saw it as an enemy country because of Pauline's support for Napoleon. As a result, Lippe left the Confederation of the Rhine. Lippe then formed alliances with Austria and Russia. Pauline encouraged her citizens to donate money to equip a volunteer army.

Lippe survived this political crisis because larger powers wanted to restore things to how they were before the wars. Many small states disappeared from the map, but Lippe's independence was confirmed at the Congress of Vienna in 1814–15, where Europe was reorganized.

Ending Serfdom

On December 27, 1808, Princess Pauline issued a decree to end serfdom in Lippe. She did this against the wishes of the Estates, who had lost much of their power since 1805. The decree became law on January 1, 1809. Pauline followed the example of other states in the Confederation of the Rhine. After the French Revolution, serfdom was widely seen as an old-fashioned and unfair system.

In her decree, Pauline explained her reasons, which were both about human rights and improving the economy. Her words were read in churches and posted publicly. She believed serfdom negatively affected people's morals, hard work, and ability to pay debts. She wanted to help the peasants and improve the country's wealth.

The decree ended two specific rules:

- The Weinkauf rule: When a serf sold their right to use a piece of land, they had to pay a fee to the landlord.

- The Sterbfall rule: When a serf died, their heirs had to give their best clothes or most valuable animal to the landlord.

This change first applied to Pauline's own serfs, but it soon extended to others. This greatly improved the social status of farmers and their families in Lippe. However, the serfdom in Lippe was not as harsh as in some other countries. The farmers were still burdened by other payments and duties, which were only removed later in the 1830s.

Constitutional Changes

The Estates (representatives of the nobility and cities) used to meet every year to discuss and decide on Lippe's affairs. When Lippe joined the Confederation of the Rhine, these rights were suspended, and Pauline gained more power. She felt she no longer needed the Estates' approval for her decisions. She wrote that she couldn't stand their "pretensions and stabbings" and their "disrespectful tone."

Pauline did not get rid of the Estates, but she largely ruled without them, much like an absolute monarch. Her relationship with them was already strained because they had refused her proposed tax on alcohol in 1805, which she wanted to use to fund a hospital.

After the Confederation of the Rhine was dissolved, the Estates demanded their old rights back, leading to a big argument with the royal family.

At the Congress of Vienna, it was decided that all German states should have a constitution that included the Estates. Pauline wrote a new constitution for Lippe herself, based on those in southern German states. This constitution was approved by the government on June 8, 1819, and was celebrated by the people. However, the Estates protested because it limited their traditional rights. They asked the Emperor to stop the Princess, calling her actions "subversive and democratic."

The German Confederation then asked Pauline to cancel the constitution. After Pauline's death, her son Leopold II and the government tried to keep her legacy alive. But after long talks with the Estates, they had to compromise, giving back some old privileges to the nobility. A new constitution finally came into effect in 1836.

Final Years

Pauline was often disappointed with her son Leopold and felt she couldn't hand over the government to him easily. She delayed the transfer several times until people started to complain loudly. Finally, she surprised her son by announcing her resignation on July 3, 1820. At first, Leopold still needed her help with government matters, but he tried to keep this private.

Pauline planned to move from Detmold to her widow's home, the Lippehof in Lemgo. However, before she could move, she died in Detmold on December 29, 1820, from a painful lung illness. She was buried in the Reformed Church in Detmold.

In 1822, an obituary (a notice of death) for Pauline was published. It criticized her policy against Prussia but excused her by saying, "Who is going to require a woman, even if she were an Empress, an independent, correct political view and steady action in matters of war?"

Children

- Leopold II, Prince of Lippe (born November 6, 1796 – died January 1, 1851)

- Prince Frederick (born December 8, 1797 – died October 20, 1854)

- Princess Louise (born July 17, 1800 – died July 18, 1800)

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |