Ramón Nocedal Romea facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

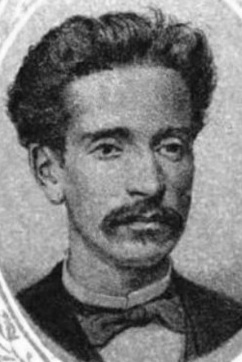

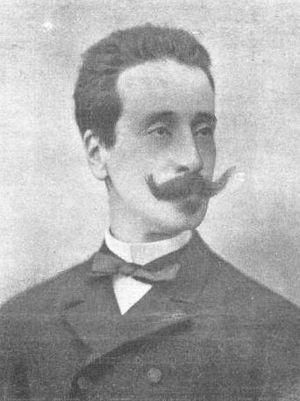

Ramón Nocedal Romea

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Ramón Nocedal Romea

1842 Madrid, Spain

|

| Died | 1907 Madrid, Spain

|

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | lawyer, politician |

| Known for | politician |

| Political party | Comunión Católico-Monarquica, Partido Católico Nacional |

Ramón Nocedal Romea (1842-1907) was a Spanish politician. He was a very strong Catholic who believed that religion should guide all parts of life, especially politics. He was a leader of a political movement called Integrism from 1888 to 1907.

Contents

Ramón's Family and Early Life

Ramón Ignacio Nocedal Romea was born into a well-known and wealthy family in Madrid, Spain. His grandfather, José Maria Nocedal Capetillo, was a successful businessman. He bought many properties and became one of the biggest landowners in Madrid. He was also a politician who served in the Spanish Senate and Cortes.

Ramón's father, Candido Manuel Patricio Nocedal Rodriguez de la Flor, was also a very important politician. He was a member of the Moderate Party and even served as the Minister of Interior for a short time. Over the years, his father became more and more conservative. In the 1860s, he joined a group called the "Neocatólicos."

Ramón's mother, Manuela del Pilar Zoila Romea Yanguas, came from a family with strong liberal views. Her uncle, Julian Romea Yanguas, was a famous Spanish actor. Another aunt was married to a prime minister.

Ramón and his two younger siblings grew up surrounded by important people in politics and art. Ramón studied law in Madrid in the early 1860s. He was an excellent student and won many awards.

In 1873, he married Amalia Mayo Albert. They did not have children, but their relationship was very loving. Amalia supported Ramón in his political choices. Ramón's nephews also became well-known figures, one as a journalist and another as a historian.

Joining the Neocatólicos

Ramón followed in his father's footsteps in politics. When Ramón started his public life in the 1860s, his father had already joined the "Neocatólicos." This group wanted to combine strong Catholic beliefs with the rules of the liberal monarchy. Ramón's father was one of their leaders.

In 1864, Ramón helped create "La Armonia," a Catholic cultural group. It was formed to challenge new ideas in education that they disagreed with. Ramón gave his first public speech there. In 1867, he started a weekly newspaper called La Cruzada. He wrote strong articles that supported Christian values and opposed new ways of thinking. He also became secretary of a law academy.

In late 1867, the Neocatólicos tried to save the monarchy of Queen Isabel II. They wanted to create a big conservative party and launched a new newspaper, La Constancia. Ramón joined the editorial team and wrote powerful articles. He was often made fun of by liberal newspapers because of his strong views. Ramón believed that ideas were more important than who was king.

The Neocatólicos' plans failed after the Glorious Revolution in 1868, which ended Isabel II's rule. La Constancia stopped publishing. In 1868, both Ramón and his father helped start the "Association of Catholics." This group was an alliance for elections. Ramón tried to become a member of the Cortes but did not win. In 1869, he joined "Catholic Youth" and became known as a great speaker and writer. He also wrote plays and short novels that were part of his Catholic political campaigns.

Becoming a Carlist: Revolution and War

After the 1868 Revolution, the Neocatólicos grew closer to the Carlists. The Carlists supported a different royal family for Spain. In 1870, many Neocatólicos decided that the Carlist model was better for protecting their conservative values. Ramón joined them.

In 1870, the Neocatólicos and Carlists formed a joint group for elections. Ramón ran for election but lost. In 1871, he ran again and won a seat in the Cortes for Valderrobres. Once in the Cortes, he became very active. He gave many speeches that were very conservative and sometimes openly against the new King, Amadeo I.

In early 1872, Ramón wrote a statement that seemed to call for a rebellion. However, historians believe that Ramón and his father preferred to achieve their goals through legal means. In the spring of 1872, Ramón ran for election again but lost his seat.

When the Third Carlist War started in 1872, Ramón and his father stayed in Madrid. They faced some minor legal issues. Their political activity was very limited. Ramón focused on his personal life: he got married in 1873 and his mother passed away in 1875. He also worked on preparing his plays for the stage.

In early 1875, Ramón and his father launched a new daily newspaper called El Siglo Futuro. It was a strongly Catholic paper and clearly very conservative. Later that year, the government ordered them to leave Spain. They traveled in Portugal and France until they were allowed to return in late 1876.

Carlist: After the War

After the Carlists lost the war in 1876, their movement was in trouble. Ramón and his father tried to revive it. They organized a large pilgrimage to Rome in 1876, which attracted about 3,000 people. This trip showed their loyalty to the Pope's teachings.

In the late 1870s, there were two main ideas within the Carlist movement. Ramón and his father believed the movement should focus on strong Catholic principles and avoid official politics. This was called "immovilismo." Others, like Marqués de Cerralbo, wanted to form a structured political party and participate in the new Spanish government. This was called "aperturismo."

Ramón Nocedal's ideas won out when the Carlist leader, Carlos VII, chose Ramón's father, Candido Nocedal, as his main political representative in 1879.

With Candido Nocedal as the leader and Ramón as his closest helper, the Carlist movement focused on religious goals. Ramón helped organize another pilgrimage to Rome in 1881, though it didn't happen. In El Siglo Futuro, he wrote about Catholic and Spanish values, putting less emphasis on regional or royal family issues.

The Nocedals were very strict. They were tough on anyone who wanted to work with the government or who disagreed with them within the Carlist movement. This caused a "newspaper war" between different Carlist groups. Many important Carlists complained about the Nocedals' strong control. Carlos VII was annoyed but didn't act until Candido Nocedal died in 1885.

There were rumors that Ramón would take over from his father. However, Carlos VII gave temporary leadership to someone else. Those who wanted to participate in elections tried to push for it. Ramón Nocedal fought back. Carlos VII decided on a compromise: the party would officially avoid elections, but individual candidates could run. This led to more arguments and confusion within the Carlist movement.

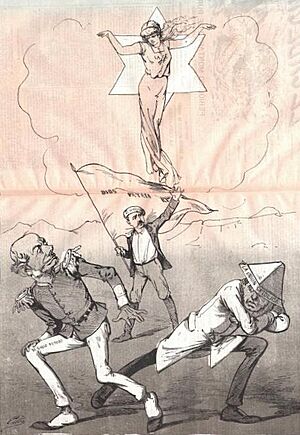

The 1888 Split

The disagreements within the Carlists grew much worse in early 1888. Ramón Nocedal refused to back down from his views, and in August, Carlos VII removed him from the Carlist movement. Both leaders then openly stated their differences.

Historians have discussed this split a lot. Some believe it was mainly a clash of personalities. Ramón Nocedal, having been raised to be a leader, felt he should succeed his father. His strong leadership style and being older than Carlos VII, who was a powerful figure himself, didn't help. Some Carlists saw Nocedal as having too much personal ambition.

Other scholars focus on the different ideas. They suggest that the role of religion was at the heart of the conflict. Nocedal wanted to make religious goals the most important, while Carlos VII wanted to keep a balance with other Carlist ideas like supporting the monarchy and regional rights. Carlists said Nocedal wanted to turn the party into a purely religious group. Integrists said Carlos VII was moving away from true Traditionalist principles.

Another idea is that this split was part of a bigger trend in Europe where very strict Catholicism was gaining power. Some historians see Integrism as a religious movement trying to take over.

Yet another view is that the two groups were always separate, even if they worked together for a while. This idea suggests that the religion-focused group was always different from the Carlists. More recently, historians combine all these factors to explain the 1888 split.

Integrist: Early Years

Many liberals thought the split would destroy the Carlist movement. Nocedal's supporters claimed they had thousands of followers. What they really had was a few important names and many newspapers. Nocedal led the group that left the Carlists. At first, they wanted to call themselves the Traditionalist Party, but in early 1889, they became the Partido Integrista Español. This name showed their belief in a complete connection between Christian and political goals. In August 1889, the party changed its name to Partido Católico Nacional, but they were usually called the Integrists.

The party's structure became stable in 1893. Each region of Spain had a local group, and Ramón Nocedal was the overall leader. This showed his strong control over the Integrist movement.

Their main goal was to create a truly Christian state and fight against liberalism. They were against party politics and parliaments. Instead, they supported the idea of "organic democracy," where society would be organized by different groups working together. The party stopped focusing on a specific king, even though Nocedal remained a strong supporter of monarchy in general. They believed in the "Social Reign of Jesus Christ," meaning that Christian principles should guide all of society.

During the 1890s, the Integrists were driven by a very strong dislike for the Carlists, even more than for the liberals. Sometimes, this dislike even led to violence. Nocedal wanted to use elections as a way to challenge and defeat Carlos VII. This rivalry was especially strong in areas where both groups had support, like the Basque Country and Navarre.

In the 1891 elections, the Integrists won 2 seats in the Cortes, while the Carlists won 5. Nocedal was very proud of his personal victory in the Azpeitia district of Gipuzkoa. He defeated the local Carlist leader there. Nocedal was a great speaker. In the 1893 elections, he won in Azpeitia again against the same opponent. Nationally, the Integrists won 2 seats, and the Carlists won 7. However, in the 1896 elections, the Integrists did not win any seats, and Nocedal also lost in Azpeitia.

Integrist: Final Years

| Integrist Mandates, 1891-1905 | |||||||||||

| year | mandates | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1891 | Azpeitia (Nocedal), Zumaya (Zuzuarregui) | ||||||||||

| 1893 | Azpeitia (Nocedal), Pamplona (Campion) | ||||||||||

| 1896 | - | ||||||||||

| 1898 | - | ||||||||||

| 1899 | Azpeitia (Olazabal) | ||||||||||

| 1901 | Azpeitia (Aldama), Salamanca (Sanchez Campo), Pamplona (Nocedal) | ||||||||||

| 1903 | Pamplona (Nocedal), Salamanca (Sanchez Campo) | ||||||||||

| 1905 | Azpeitia (Sanchez Marco), Pamplona (Nocedal) | ||||||||||

In the mid-1890s, Nocedal realized that his plan to create a large Catholic conservative party across Spain had not fully succeeded. But he remained firm in his beliefs and felt it was his duty to represent strong Christian values and fight against liberalism. Other party members were not as strict, and Nocedal had to deal with people leaving the party until his death. However, no one seriously threatened his leadership.

Some Integrist leaders suggested making the party a looser Catholic alliance, but Nocedal rejected this idea, and they left. Nocedal also removed a group that supported Arturo Campión, which led to the loss of a newspaper and some leaders in Navarre. In the late 1890s, the Integrist party faced problems in its stronghold, Gipuzkoa. Nocedal also expelled a Jesuit priest in 1899, accusing him of teaching wrong ideas.

In 1898, Nocedal was elected a senator but did not take his seat for unknown reasons. As the new century began, Integrists and Carlists started to work together more at a local level. They made agreements for elections in Gipuzkoa and Navarre. In 1901, Nocedal ran in Pamplona and lost, but he still entered the Cortes due to a legal appeal. In 1903, Nocedal was elected from a joint Integrist-Carlist-Conservative list in Pamplona. He was re-elected on the same ticket in his last campaign in 1905.

Even though Nocedal based all his political work on religious principles and wanted to be loyal to the Church, he mainly had strong support from local priests in the Basque and Navarrese regions and from the Jesuits. His relationship with the higher Church leaders was often difficult. The bishops wanted to stay on good terms with the government, and they did not like the Integrists' strict and anti-establishment approach. Nocedal often disagreed with the bishops on political issues.

When the Vatican changed its strategy in the early 20th century, Nocedal liked the new, more democratic way of making policies even less. He strongly opposed the idea of choosing the "lesser of two evils" in politics. This public debate led to a Church letter in 1906, and a Vatican representative blamed Nocedal for the failure of a large Catholic political group. Even the Jesuits turned away from Integrism at this point. As perhaps his last political act, Nocedal joined forces with another Carlist leader and created a very strict electoral platform, but he died before it could be tested.

See also

In Spanish: Ramón Nocedal para niños

In Spanish: Ramón Nocedal para niños

- Integrism (Spain)

- Cándido Nocedal

- Neocatólicos

- La Constancia

- Carlism

- Ultramontanism

- Partido Católico Nacional

- Electoral Carlism (Restoration)

- Navarrese electoral Carlism (Restoration)

- El Siglo Futuro

- Félix Sardà y Salvany

- Juan Olazábal Ramery

- Manuel Senante Martinez

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |