Report of 1800 facts for kids

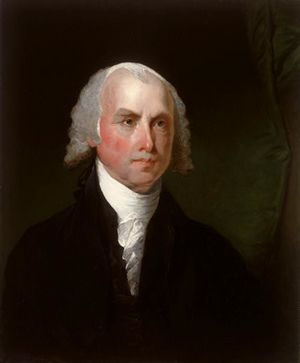

The Report of 1800 was an important document written by James Madison. It argued that individual states should have more power under the U.S. Constitution. It also spoke out against the Alien and Sedition Acts. The state of Virginia officially approved this Report in January 1800.

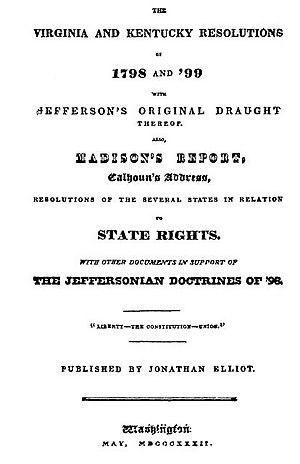

This Report mostly added to ideas from the 1798 Virginia Resolutions. Its main goal was to answer people who had criticized those earlier Resolutions. The Report of 1800 was a key paper about the Constitution before 1817.

Later, the ideas in the Resolutions and the Report were used during the nullification crisis in 1832. In that crisis, South Carolina said that federal tariffs (taxes on goods) were against the Constitution. They tried to make these laws invalid in their state. However, James Madison himself did not agree with nullification. He said his arguments did not support such actions. Today, people still discuss if Madison's ideas truly supported nullification. They also wonder if his views from 1798-1800 fit with his other work.

Why the Report Was Needed

James Madison was a member of the Republican Party. He was chosen to be part of Virginia's government in 1799. A big part of his job was to defend the Virginia Resolutions from 1798. Madison had also written these Resolutions.

The Virginia Resolutions are often talked about with the Kentucky Resolutions. Thomas Jefferson wrote the Kentucky Resolutions around the same time. Both were a response to laws passed by the national government. This government was mostly controlled by the Federalists.

The most important of these laws were the Alien and Sedition Acts. These four laws gave the President power to send away foreigners. They also made it harder for foreigners to become citizens. Plus, they made it a crime to print bad things about the government. Republicans were very upset by these laws. So, Madison and Jefferson wrote the Resolutions. The states of Virginia and Kentucky then approved them.

Over the next year, other state governments strongly criticized the Virginia Resolutions. They said that the Supreme Court of the United States should decide if federal laws were constitutional. They also believed the Alien and Sedition Acts were constitutional and necessary. The Federalists even accused the Republicans of wanting to break up the country.

Thomas Jefferson, a leader of the Republican Party, wrote to Madison in 1799. He suggested a plan to get more public support for the ideas in the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions. Jefferson wanted the states to answer the criticisms. He also wanted them to protest the laws and save their rights. He hoped people would agree with them. But he also said that if things got too bad, they might have to leave the Union.

Madison visited Jefferson in September 1799. Their talk was important. Madison convinced Jefferson to change his mind about leaving the Union. Jefferson later wrote that he would "retreat readily" from that idea. This showed that Madison helped soften Jefferson's more extreme views.

Jefferson wanted to help write the Report. He planned to visit Madison on his way to Philadelphia, the nation's capital. But James Monroe advised Jefferson not to meet Madison. Monroe said another meeting between the two top Republican leaders would cause too much talk. So, Madison was left to write the Virginia Report by himself. Jefferson still stressed how important this work was.

Creating the Report

The Virginia Assembly meeting started in early December. Madison began writing the Report in Richmond. He was sick for a week, which delayed him. On December 23, Madison asked for a special committee to be formed. This committee would respond to the criticisms from other states. Madison became the chairman of this seven-member committee.

The committee quickly finished a first version of the Report. It was brought before the House of Delegates on January 2. Even though the Republicans had a strong majority, the Report was debated for five days.

The main argument was about the meaning of the third Virginia Resolution. This resolution said that the federal government's powers came from an agreement between the states. It also said that if the government used powers it wasn't given, the states had the right to step in. This part had been the main target of the Federalist attacks.

The Report was changed to make it clearer. It stressed that the people themselves, acting through their states, were the ones who agreed to the Constitution. The amended Report passed the House of Delegates on January 7. It then passed the Senate within the next two weeks.

Virginia Republicans liked the Report. The Assembly printed 5,000 copies to share in the state. But the public did not react much to it. It seemed to have little effect on the presidential election of 1800. However, that election was a big win for the Republicans.

Other states did not seem interested in re-discussing the 1798 Resolutions. There was little public talk about it outside Virginia. Jefferson wanted copies to give to Republican members of Congress. He even asked Monroe for a copy when they didn't arrive. Even with Jefferson's approval, the national reaction was not strong.

Still, Madison's Report was important. It made the legal arguments against the Alien and Sedition Acts clearer. It also strengthened the idea of states' rights. It especially highlighted the Tenth Amendment as a way to protect states from federal power.

Main Ideas of the Report

The main goal of the Report was to support and expand the ideas in the Virginia Resolutions. One big aim was to get the Alien and Sedition Acts canceled. Madison wanted to do this by showing clearly that these Acts broke the Constitution.

In his Report, Madison pointed out many ways the Acts went against the Constitution. The Alien Act gave the President power to deport friendly foreigners, which was not listed in the Constitution. The Sedition Act was also wrong. Madison argued that the government could not protect its officials from criticism or libel. He said that special laws against the press were "expressly forbidden by a declaratory amendment to the constitution."

To fix these problems, Madison said citizens should have a full right to free speech. He wrote that allowing the government to punish speech would protect officials "if they should at any time deserve the contempt or hatred of the people." Freedom of the press was necessary because, even with its problems, "the world is indebted to the press for all the triumphs which have been gained by reason and humanity over error and oppression."

The Report supported a strict reading of the First Amendment. Federalists thought this amendment only limited Congress's power over the press, but that some power still existed. Madison argued that the First Amendment completely stopped Congress from interfering with the press.

More generally, the Report strongly argued for the power of individual states. This is what it is best known for. The main idea was that the states were the original parties to the federal agreement. Therefore, individual states were the final judges of whether that agreement had been broken. This idea is called the compact theory.

This argument in the Resolutions had made Federalists say Republicans wanted to break away. In the changed Report, this idea was softened. It emphasized that states, as political groups of people, had this power. This helped the Republican cause. It challenged the idea that only Congress or federal courts could interpret the Constitution.

Madison also defended Virginia Republicans. He said that even if people disagreed with the compact theory, the Virginia Resolutions and the Report of 1800 were just protests. States certainly had the right to protest. He said they were "expressions of opinion, unaccompanied with any other effect than what they may produce on opinion by exciting reflection." By choosing to influence public opinion instead of taking direct action, Madison showed that Republicans were not trying to break up the country.

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |