Rio Nuñez incident facts for kids

The Rio Nuñez incident was an important event that happened in 1849. It took place near a river called the Nunez River, in a town called Boké, which is now part of the country Guinea. This event involved ships from Belgium and France firing on a local village. This caused problems for two British traders who lost their goods. The whole incident started because of a power struggle between local leaders in the area.

Contents

Why Did It Happen?

European Countries Competing in West Africa

In the 1840s and 1850s, European countries like France and Britain were starting to compete for control in West Africa. They wanted to set up colonies and trading posts. The Nuñez region was located between French areas like Senegal and British areas like Gambia and Sierra Leone. French traders were finding it harder to do business because more traders from Britain, Belgium, and America were arriving.

Belgium's Early Plans for Colonies

King Leopold I of Belgium was very interested in colonies. He believed Belgium needed its own colonies to become a stronger country. Since 1845, Belgium had been looking at the Rio Nuñez area. They saw it as a good place for a trading outpost. A merchant named Abraham Cohen convinced the King that it was a great chance.

So, on December 17, 1847, a Belgian navy ship called the Louise Marie was sent to explore the area. It arrived in January 1848 and stayed in the Rio Nuñez in February and March. The crew learned that the river could be used for trade, but not during the rainy season.

Local Power Struggles in Rio Nuñez

The local people in the area were divided. After their king died in 1846, two brothers, Tongo and Mayoré, both wanted to be the new leader. Tongo was supported by the British at first, while Mayoré was supported by the French. Mayoré also had help from another group called the Nalous, who promised to fight for him.

Tongo was angry and set fire to a village, but he was defeated and had to retreat. Because of this local conflict, France and Britain made a treaty. This treaty said that neither country should get involved in the fighting along the river.

Belgium Steps In

A Belgian officer named Van Haverbeke saw an opportunity. He signed an agreement with Lamina, who was the King of the Nalous. In this agreement, Lamina gave control of both sides of the Rio Nuñez to the King of Belgium. In return, the Belgians would pay Lamina regularly and protect him.

The Louise-Marie ship then sailed back to Belgium and returned with the treaty to be made official. Meanwhile, Abraham Cohen was put in charge of trade in the region.

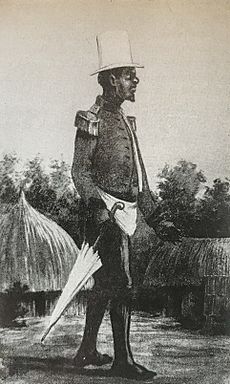

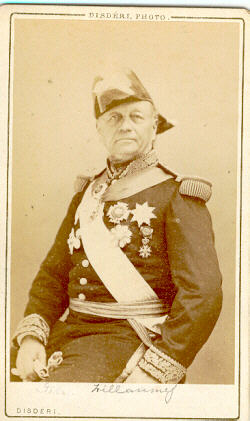

The French commander in the area, Édouard Bouët-Willaumez, was not happy about the Belgians' return. He thought the river was very important for France. On February 11, 1849, Lamina visited the Belgian ship and was very pleased to receive a new uniform from the Belgians.

After signing the treaty with Lamina, the Belgians wanted to make a deal with Mayoré. But Mayoré was becoming less friendly towards Europeans. He had even kicked out a Frenchman named Ismaël Tay, who was his brother-in-law, and kidnapped Ismaël's wife and child. Mayoré worried that Ismaël's family might try to claim his throne.

The Belgians, along with a local merchant named Bicaise, went to see Mayoré. They found Mayoré's people building a house for two English merchants, Braithwaith and Marin. This was happening on land that belonged to Bicaise, without his permission. These British traders had arrived at the same time as the Louise-Marie and had given many gifts to Mayoré to gain his favor.

Belgian officers landed near Bicaise's house. Soon, about 400 local people, armed with rifles, surrounded them. Van Haverbeke then went to Mayoré and demanded an answer by 11 PM, or he would attack. Around 10 PM, they received a positive answer. They left the village with Ismael's wife and child, who had been rescued without Mayoré knowing.

Escalation of the Conflict

On the 27th, Van Haverbeke learned that Mayoré planned to take back Ismael's wife and child. He ordered his troops to check every ship going up the river. The same day, a British ship commander protested the Belgians' actions, saying it went against Britain's treaty with France. However, he admitted that his superiors had misunderstood the treaty, and it did not involve Belgium or other countries.

Ismael then found out his family had been taken prisoner again by Mayoré. The French and Belgians met and decided to remove Mayoré from power and make Lamina the new leader. They sent a group to try one last time to get the prisoners back. Meanwhile, locals told the expedition that the two British traders had given about 30 guns to Mayoré's forces the day before, even though they were flying a white flag (a sign of peace).

Later that day, a group of Foulhas arrived and spoke against Mayoré. Even some of Mayoré's own chiefs came to say that Mayoré was being influenced by the British traders. They wanted to return Ismael's family, unlike their king.

Five days later, on the 16th, after many talks between French and Belgian commanders, the Louise-Marie started blocking the river. On the 17th, a letter was sent to the British merchants. It told them to leave the area or their belongings would be destroyed during the attack. Two days later, they came to Bicaise's home with a peace offer from Mayoré. But the French and Belgians did not trust Mayoré.

On the 20th, a letter from the British traders arrived. It stated they would hold the French and Belgian governments responsible for any damage they suffered, as they refused to leave Boké. On the 23rd, Tongo and 150 of his men arrived with red flags. The French then gave them weapons. On the same day, the French stopped the two British traders who were trying to escape and kept them on board until the attack was over. An official declaration of war was then sent to Mayoré.

The Attack on Boké

On the morning of March 24, 1849, Mayoré's men, armed with rifles, were on the high ground. On the merchants' hut, both the Union Jack (British flag) and a white flag could be seen. The French officer de la Tocnaye decided to open fire on the village to set it on fire. The other ship soon followed.

After about 15 minutes, the order was given to land troops. They quickly reached the riverside. The warships provided strong support with mortar fire. Boké was captured within 40 minutes. The village was burned, along with the British merchants' stores.

What Happened Next?

Admiral Bouët-Willaumez hoped that the Nunez region would officially become a French protectorate (a territory controlled by France). However, the attack did not secure the region for France as he had hoped. Both France and Belgium tried to keep the details of the incident quiet.

The British Prime Minister, Viscount Palmerston, tried to make France pay for the damage caused during the incident. But he was not successful, and the issue lasted for four years.

This incident was an early sign of the "Scramble for Africa", a time when European powers rapidly took control of African lands. As Bouët-Willaumez had hoped, it did lead to France gaining more control over the Nunez region. In 1866, French forces occupied Boké. This event was one of the first signs that France would become a major power in West Africa, leading to the creation of French West Africa.

See Also

- Belgian colonial empire

- Guillaume Delcourt

Sources

- Anrys, H., de Decker de Brandeken, J-M., Eyngenraam, P., Liénart, J-C., Poskin, E., Poullet, E., Vandensteen, P., Van Schoonbeek, P., Verleyen, J. (1992). La Force Navale - De l'Amirauté de Flandre à la Force Navale Belge. Comité pour l'Étude de l'Histoire de la Marine Militaire en Belgique, Tielt, Impremerie Lannoo. pp. 111–115: "L'affaire du Rio Nunez".

- Du Colombier Thémistocle (1920). Une expédition Franco-Belge en Guinée. La Campagne de le goëlette belge Marie-Louise dans la Colonie Belge du Rio Nunez (1849), Bulletin de la Société Belge d'Études coloniales.

- Leconte, Louis (1952). Les Ancêtres de Notre Force Navale. Brussels, Pauwels Fils. pp. 161–199: "L'affaire du Rio Nunez".

- Maroy, Ch. (1930). "La colonie belge du Rio Nunez et l'expédition franco-belge de Bokié en 1849". Bulletin d'Études et d'Informations de l'École supérieure du Commerce, Antwerp, September–October edition, P.47.

- Leconte, Louis (1945), La marine de guerre belge (1830-1940), Brussels, La Renaissance du Livre, coll. « "Notre Passé" », 1945, chap. 5 (« Le service Ostende-Douvres. L'affaire du Rio-Nunez. »), pp. 51–64.

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |