Ruby Payne-Scott facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ruby Payne-Scott

|

|

|---|---|

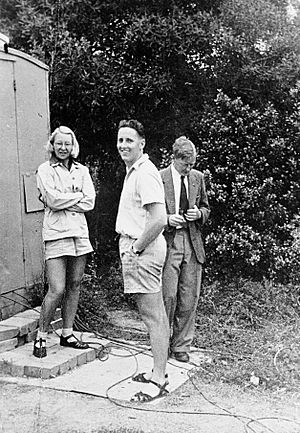

Payne-Scott as a student in the 1930s, possibly while she was studying at the University of Sydney (1929–1932)

|

|

| Born |

Ruby Violet Payne-Scott

28 May 1912 Grafton, New South Wales, Australia

|

| Died | 25 May 1981 (aged 68) Mortdale, New South Wales, Australia

|

| Nationality | Australian |

| Alma mater | University of Sydney |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Radio astronomy, radiophysics, Radio-frequency engineering |

| Institutions | CSIRO |

Ruby Violet Payne-Scott (born May 28, 1912 – died May 25, 1981) was an amazing Australian scientist. She was a pioneer in radiophysics and radio astronomy. She was also the first woman to become a radio astronomer.

Contents

Early Life and School Days

Ruby Payne-Scott was born on May 28, 1912, in Grafton, New South Wales, Australia. Her parents were Cyril and Amy Payne-Scott. Later, she moved to Sydney to live with her aunt.

Ruby went to Penrith Public Primary School and Cleveland-Street Girls' High School. She finished her high school studies at Sydney Girls High School. She was a very bright student, getting high marks in math and botany.

University Studies

Ruby won two scholarships to study at the University of Sydney. There, she learned about physics, chemistry, mathematics, and botany. In 1933, she earned her first degree, a Bachelor of Science (BSc). She was only the third woman to get a physics degree from that university.

She continued her studies and earned a Master of Science (MSc) in physics in 1936. In 1938, she also got a Diploma of Education, which meant she could teach.

Early Career and Research

In 1936, Ruby Payne-Scott worked at the Cancer Research Laboratory at the University of Sydney. She teamed up with William H. Love for an interesting study. They wanted to see if the Earth's magnetism affected living things.

They grew chicken embryos in very strong magnetic fields. These fields were up to 5,000 times stronger than the Earth's magnetic field. They found no differences in the embryos. This showed that the Earth's magnetism had little effect on living processes. Before this, many people believed the Earth's magnetic field greatly affected humans.

After her cancer research, Ruby taught at St Peter's Woodlands Grammar School from 1938 to 1939.

Working at AWA

Soon after teaching, Payne-Scott joined AWA. This was a big company that made electronics and ran radio communication systems in Australia. She was first hired as a librarian. However, her skills quickly led her to lead the measurements lab. She also did important electrical engineering research. She left AWA in August 1941 because she was not happy with the research environment there.

Contributions to Radar and Radio Astronomy

On August 18, 1941, Payne-Scott joined the Radiophysics Laboratory. This lab was part of the CSIRO, an Australian government science agency. During World War II, she worked on top-secret radar technology. She became Australia's expert on using radar to find aircraft.

After the war, in 1948, she wrote a detailed report. It explained what affected how well radar screens (called PPI displays) showed aircraft. She also helped improve early radar systems that used microwaves.

Shifting to Radio Astronomy

After the war, the Radiophysics Lab started using radar systems for science. Ruby was key in setting these new goals. She was special because she was both a physicist and an electrical engineer. Most of her colleagues did not have her strong physics background.

In October 1945, she worked with Joe Pawsey and Lindsay McCready. They wrote to the science journal Nature. They showed a link between sunspots and more radio signals from the Sun. This was published in February 1946.

In December 1945, she wrote a summary of all the knowledge and measurements from the Radiophysics Lab. She also suggested new research ideas that guided the group's future work.

Pioneering Radio Interferometry

In February 1946, Payne-Scott, McCready, and Pawsey used their observation sites by the sea-cliff. They performed the first radio interferometry for astronomy. This method uses two or more antennas to act like one giant antenna. Their observations proved that strong radio 'bursts' came from sunspots.

Their paper also suggested using Fourier synthesis in radio astronomy. This idea was a hint at how the field would develop later, using many antennas to create detailed images.

From 1946 to 1951, Ruby focused on these 'burst' radio emissions from the Sun. She is known for discovering Type I and Type III bursts. She also gathered data that helped describe Type II and Type IV bursts. For this work, she and Alec Little designed a new 'swept-lobe' interferometer. This device could map the Sun's radio emission strength and polarization every second. It would also automatically record to a movie camera when emissions were strong.

Leaving Science and Second Career

In 1951, Ruby Payne-Scott's science career ended suddenly. She decided to resign to start a family. At that time, there was no maternity leave for women in her job.

In August 1952, she briefly returned to radio astronomy. She took part in a big science meeting, the 10th International Union of Radio Science General Assembly, at the University of Sydney.

From 1963 to 1974, Payne-Scott returned to teaching. She taught at Danebank School in Sydney.

Personal Life and Family

Ruby Payne-Scott was a strong supporter of women's rights. She believed in equal opportunities for women. She loved bushwalking and cats. She also enjoyed knitting.

Marriage and Work Challenges

Ruby Payne-Scott secretly married William ("Bill") Holman Hall in 1944. At that time, the government had a rule called a marriage bar. This rule meant that married women could not hold a permanent job in public service. She kept working for CSIRO while secretly married.

In 1949, new CSIRO rules brought up the issue of her marriage. The next year, she had disagreements with the head of CSIRO, Sir Ian Clunies Ross, about married women in the workplace. As a result, Ruby lost her permanent job at CSIRO. However, her salary stayed the same as her male co-workers. In 1951, just before her son was born, she resigned because there was no maternity leave.

After leaving CSIRO and her marriage became known, Ruby took her husband's last name, Hall. She was then known as Ruby Hall. They had two children:

- Peter Gavin Hall – He became a famous mathematician who studied statistics.

- Fiona Margaret Hall – She became a well-known Australian artist.

Later Life and Legacy

Ruby Payne-Scott died in Mortdale, New South Wales, on May 25, 1981. She passed away three days before her 69th birthday. Towards the end of her life, she suffered from Alzheimer's disease.

In 2018, The New York Times wrote a special obituary for her. It explained how her work helped create the new science field of radio astronomy.

Ruby Payne-Scott's contributions are still remembered today:

- In 2008, CSIRO created the Payne-Scott Award. This award helps researchers who are returning to work after taking time off for family.

- Danebank School, where she taught, holds an annual Ruby Payne-Scott Lecture. Important women scientists give these talks.

- In 2017, the University of Sydney started the Payne-Scott Professorial Distinctions. These honor professors who have made great contributions to the university.

Professional Roles

- Research fellow, Cancer Research Committee, University of Sydney, 1932–35

- Teacher, Woodlands Church of England Grammar School, 1938–1939

- Engineer, AWA Ltd, 1939–41

- Scientist, Division of Radiophysics, CSIR (now CSIRO), 1941–51

- Homemaker, 1951–63

- Mathematics/science teacher, Danebank Church of England School, Sydney, 1963–74

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Ruby Payne-Scott para niños

In Spanish: Ruby Payne-Scott para niños

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |