Siege of Tortosa (1148) facts for kids

The siege of Tortosa was a big military event that happened from July 1 to December 30, 1148. It was part of the Second Crusade (1147–49) in Spain. An army made up of soldiers from many different places, led by Count Raymond Berengar IV of Barcelona, surrounded the city of Tortosa. At that time, Tortosa was part of the Almoravid Emirate, a Muslim kingdom. After six months, the defenders of the city gave up.

This military action started with an agreement between Barcelona and the Italian city of Genoa in 1146. The Genoese had previously attacked Muslim lands. They also agreed to help the Castilians attack Almería. The Pope approved these plans, linking them to the larger Second Crusade aimed at the Holy Land. People who joined the siege of Tortosa were called "pilgrims," just like those traveling to the Holy Land.

The siege was a very tough fight. Both sides used large siege engines. Even after the outer walls were broken, the defenders fought hard in the streets. They tried to stop the crusaders from reaching the main fortress, called the citadel. Eventually, the citadel itself was attacked. The defenders then asked for a 40-day break in fighting, which they received before surrendering. Unlike other battles, there was no mass killing or stealing. The people living in Tortosa, who were both Muslims and Jews, were allowed to stay. Christians quickly moved into the city.

Taking Tortosa was a very important step in the Reconquista. This was the long effort to retake Spain from Muslim rule. After Tortosa, Raymond Berengar IV went on to conquer Lleida in 1149. He did this on his own, without help from Genoa or the Pope.

Contents

Why Tortosa Was Important

Past Attacks on Tortosa

Tortosa is about 12 miles (19 km) up the Ebro river from the Mediterranean Sea. It sits on the east side of the river, with hills to its north and east. It was a busy seaport with large docks and a strong inner fortress called the suda. A big part of the city outside the suda was protected by another outer wall. In 1148, Tortosa had about 12,000 people and was known as a center of culture in the Islamic world.

In 1081, Tortosa became the center of a small independent kingdom called the taifa of Ṭurṭūsha. From then on, Christian armies often targeted it. They either wanted money from its ruler or planned to conquer it completely. When Tarragona was captured in 1088, holding Tortosa became even more important. Without Tortosa, Tarragona could not be safe.

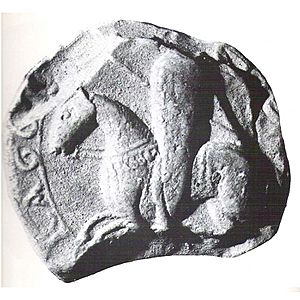

In 1092, Genoa and Pisa attacked Tortosa together. In 1095, Count Berengar Raymond II of Barcelona also attacked it. Two years later, in 1097, his nephew, Raymond Berengar III of Barcelona, surrounded it with help from a Genoese fleet. This attack failed, but it was seen as a holy war, similar to the First Crusade.

Tortosa was taken by the Almoravids around 1114. It might have been captured by Christians soon after, but it was back in Almoravid hands by 1118. In 1116, Raymond Berengar III tried to get help from Genoa and Pisa for an attack on Tortosa. The Pope even approved this plan, but the attack never happened. Another planned trip in 1121 also received papal approval like a crusade but did not start. In 1128, the Count of Barcelona tried to get naval help from Count Roger II of Sicily for an attack on Tortosa, but other events stopped these plans. In 1129, people started moving back to Tarragona in large numbers.

Barcelona was not the only power interested in taking Tortosa. In 1086, King Peter I of Aragon surrounded it. In 1134, his brother, Alfonso the Battler, died during a campaign aimed at Tortosa. In 1137, Aragon and Barcelona joined forces. This happened when Raymond Berengar IV was set to marry Alfonso's niece, Queen Petronilla of Aragon. This meant the Count of Barcelona could use resources from Aragon to help conquer Tortosa.

Gathering the Army

In 1146, a fleet from Genoa, led by Consul Caffaro di Rustico, attacked the Almoravid island of Menorca. Then they sailed to the mainland and surrounded Almería. Almería was forced to pay a tribute. During these actions, Genoa made a deal with King Alfonso VII of León. The Genoese fleet would help Alfonso conquer Almería the next May. In return, Genoa would get one-third of the city and would not have to pay any taxes in Alfonso's lands. This agreement then led to a similar deal with Raymond Berengar IV. The Genoese would help him take Tortosa after Almería was captured. In return, Genoa would get one-third of Tortosa and would not have to pay taxes in Raymond Berengar's lands. These lands included Provence, where he was acting as ruler for his nephew.

Besides soldiers from Provence, other armies from southern France, known as Occitans, joined the fight. William VI of Montpellier, the lord of Montpellier, who also helped at Almería, was there. So were Bernard IV of Anduze, Roger I Trencavel, and Peter II, Viscount of Béarn. William VI brought his son, William VII of Montpellier, with him. He had already promised his son a share of Tortosa after it was conquered.

On October 5, 1146, Pope Eugenius III issued a special letter called a bull, Divina dispensatione I. It encouraged Italians to join the Second Crusade. A second bull, Divina dispensatione II, was issued on April 13, 1147. This letter specifically approved the military trips in Spain as crusades, possibly because Genoa asked for it. There were three such trips planned at the time. Besides the attacks on Tortosa and Almería, King Afonso I of Portugal had just conquered Santarém and was getting ready to besiege Lisbon. On June 22, 1147, Eugenius issued another bull. It asked Christians to help the Count of Barcelona "in driving out the non-believers and enemies of the cross of Christ." He might have also sent Nicholas Breakspear (who later became Pope Adrian IV) to Spain. As an Englishman, Nicholas might have helped convince Balluini de Carona, the leader of the English and Norman groups, that this was a worthy cause.

The army that attacked Tortosa included soldiers from Aragon, Catalonia, and Occitania, who were under Raymond Berengar's rule. It also had the Genoese army, which he had recruited in 1146. On top of that, crusaders from northern Europe joined, including Englishmen, Flemings (from Flanders), and Normans. It is likely that some of these English, Flemish, and Norman crusaders had fought in the Lisbon campaign. Another part of that army had gone to the Holy Land and was fighting in the siege of Damascus at that time. The Royal Chronicle of Cologne is the only source that says the English at Tortosa were also at Lisbon. It also states that they continued to the Holy Land afterward.

Among Raymond Berengar's Catalan forces were some knights from military orders. These included Templars from Montblanc, some Hospitallers, and some Knights of the Holy Sepulchre. These three orders were supposed to receive money and land from Alfonso the Battler's will. However, his will was ignored after his death. Instead, Ramiro II of Aragon, the father of Raymond Berengar's wife Petronilla, became king.

By an agreement on May 25, 1148, Count Ermengol VI of Urgell served in Raymond Berengar's army. In return, he would get a large share of the land around Lleida when that city was conquered.

According to the Deeds of the Counts of Barcelona, Raymond Berengar's army was 200,000 strong. However, a more realistic guess is about 2,000 soldiers.

The Siege of Tortosa

Surrounding the City

The Genoese fleet that helped conquer Almería left a small group of soldiers there. Then, it sailed to Barcelona. From Barcelona, two ships carrying two of the consuls went back to Genoa. They brought money from the treasures found in Almería to help pay off some of Genoa's debts. The rest of the fleet stayed in Barcelona for the winter. In the spring, more soldiers arrived. During the spring, wood was cut from the forests near Barcelona. This wood was used to build machines for the siege.

The campaign might have been delayed because of a disagreement between Raymond Berengar and King García Ramírez of Navarre. The King of Navarre seemed to have taken the chance to capture the Aragonese town of Tauste in March. This led to several meetings. Raymond Berengar met with Alfonso VII at Soria and with García Ramírez at Gallur. These meetings resulted in an agreement, though we don't know the exact details. This agreement made sure the border between Navarre and Aragon would stay peaceful during the rest of the Tortosa campaign.

The Genoese and Catalan fleets sailed from Barcelona on June 29. They entered the Ebro river on July 1, 1148. The Genoese fleet was led by several consuls. It stopped two miles before the city. The Genoese commanders and Raymond Berengar then checked Tortosa's defenses. They decided to divide the army into three parts. Half of the Genoese army, with some Catalan knights, camped on the riverbank just outside the outer city walls to the south. The rest of the Genoese, the Catalans, and the Occitans, led by Raymond Berengar and his seneschal, Guillem Ramon II de Montcada, camped above the city on a hill called Banyera to the northeast. The military orders and the crusader groups from England, Normandy, and Flanders camped next to a mill on the river, just north of the town.

Attacking the City

Some Genoese soldiers were eager to fight. They led the first attack, which resulted in many soldiers being hurt on both sides. The Genoese then built two large siege towers. They managed to break through the outer wall from the southeast. They continued to use the tower inside the city to destroy houses and clear a path to the mosque. They reached the mosque only after very heavy fighting. The defenders had prepared many layers of defense.

The Catalan–Occitan force on Banyera first had to fill a deep ditch. This ditch was about 42 meters (138 feet) wide and 32 meters (105 feet) deep. They filled it with wood and stones before they could attack the walls. This work was likely done mostly by the Genoese soldiers. Then, they built a third tower that could hold 300 men and a stone-throwing machine. Raymond Berengar probably paid for this tower. After the outer wall was broken, they moved this tower up to the walls of the main fortress (the suda) from the east side. The defenders fought back with their own stone-throwing machines. These could throw stones weighing 200 pounds (91 kg). One corner of the tower was badly damaged by one of these stones, but the Genoese engineers managed to fix it. The tower was then strengthened with ropes woven together to protect it from more attacks.

At this point, Raymond Berengar's soldiers had not been paid, and most of them eventually left the siege. Only about twenty knights and the Genoese soldiers stayed with him. With the help of some mangonels (another type of siege engine), they broke through the suda's walls. The defenders then asked for a 40-day break in fighting on November 20. This was granted in exchange for 100 hostages. During these 40 days, they sent messengers to other Muslim kingdoms, especially the taifa of Balansīya (Valencia), asking for help. However, the recent arrival of the Almohads in Spain meant these kingdoms could not afford to weaken themselves to help Tortosa. Unfortunately for the defenders of Tortosa, the Muslim ruler to the immediate south, Ibn Mardanīš, had an agreement with Raymond Berengar.

When the 40-day break ended, after six months of siege, the people of Tortosa surrendered on December 30. As a later document stated: "Tortosa, the key of the Christians, the glory of the people, an ornament of the whole world, was captured."

During the siege, the English soldiers who died in battle were buried in a special cemetery. After the surrender, this cemetery was given to the Canons of the Holy Sepulchre. This way, even in death, the pilgrims could feel like they had fulfilled their promise to go to Jerusalem.

What Happened After

Tortosa was captured with very little bloodshed. This was probably because past experiences, like with Tarragona, showed how hard it was to get Catalans to move into a city. Unlike his description of Almería's fall, Caffaro does not mention any stealing or taking of slaves when Tortosa fell. The Muslim and Jewish people stayed in the city. Raymond Berengar gave the Jews special rights and freedoms. However, the Muslims were limited to a special area called the aljama, which was outside the main city walls. They were given one year to give up their houses inside the city. The aljama had some self-governance, with its own leaders and religious courts. In return for being able to practice their religion freely, the people of the aljama paid a tax to the count. When they surrendered, they also had to pay a special payment.

The walled city was divided into three parts. The suda and the city's government were given to the seneschal Guillem Ramon. The port and docks went to Genoa. The rest went to Raymond Berengar. He gave one-fifth of the income from the countryside and the outer castles to the Templars. They were in charge of keeping the area safe. In 1150, Genoa's share was controlled by Balduino di Castro and Guglielmo Tornello. But in 1153, Genoa sold its part of Tortosa to Raymond Berengar for 16,000 maravedíes (a type of coin). The English and Norman soldiers in Tortosa were given land and houses both inside and outside the city walls. Many of them stayed in this new frontier town. This is shown by the many old documents that still exist in monastery and cathedral records.

After taking Tortosa, Raymond Berengar led a stronger army about 90 km (56 miles) inland to besiege Lleida in the spring of 1149. On October 24, Lleida surrendered. This campaign was started by the count himself. It did not have help from Genoa or the English-Flemish forces. People at the time did not seem to see it as a crusade, even though Lleida was arguably more important strategically than Tortosa.

See also

In Spanish: Conquista de Tortosa para niños

In Spanish: Conquista de Tortosa para niños

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |