Simla Convention facts for kids

| Convention Between Great Britain, China, and Tibet | |

|---|---|

Tibetan, British and Chinese participants and plenipotentiaries to the Simla Treaty in 1914

|

|

| Drafted | 27 April 1914 |

| Signed | 3 July 1914 |

| Location | Simla, Punjab Province, British Raj |

| Expiry | 23 May 1951 29 October 2008 (per United Kingdom) |

| Negotiators | |

| Signatories | |

| Ratifiers | |

| Languages | |

The Simla Convention was an important meeting held in Simla, India, between 1913 and 1914. It involved representatives from China, Tibet, and Great Britain. The main goal was to decide the future status of Tibet.

The agreement suggested dividing Tibet into two parts: "Outer Tibet" and "Inner Tibet". Outer Tibet would be managed by the Tibetan government in Lhasa. China would have a special influence called "suzerainty" over it, but would not control its daily running. Inner Tibet, however, would be directly under China's control.

This convention also drew new borders. One border was between Tibet and China. The other was between Tibet and British India, which became famous as the McMahon Line.

A first version of the agreement was approved by all three countries on April 27, 1914. But China quickly said it would not accept it. A slightly changed version was signed on July 3, 1914, but only by Britain and Tibet. China's representative, Ivan Chen, refused to sign. Britain and Tibet then declared that the agreement would apply to them. They also said China would not get any benefits from it until they signed.

Contents

Why the Simla Convention Happened

Tibet's Status and Foreign Influence

Tibet was like a special territory under China's indirect rule. As China's power weakened, Britain and Russia became more interested in Tibet. This period was known as the "Great Game". Britain worried about Russia gaining too much influence in Tibet. This was because a Russian-born monk, Agvan Dorzhiev, was close to the 13th Dalai Lama.

To protect its interests in India, Britain decided to act. In 1904, British forces, led by Sir Francis Younghusband, entered Tibet. They made a treaty with Tibet, called the 1904 Convention of Lhasa. This showed how weak China's control over Tibet had become.

China's Renewed Control and Revolution

After the British expedition, China tried to get back its strong influence in Tibet. This led to some local uprisings. In 1910, China sent its army to Tibet. They almost took full control of Tibet and nearby areas. However, China's Qing dynasty fell apart in 1911 during the Xinhai Revolution.

After the Qing dynasty collapsed, the Tibetan government in Lhasa kicked out all Chinese forces. Tibet then declared itself independent in 1913. But the new Republic of China did not accept this independence.

The Simla Conference

In 1913, Britain called for a meeting in Simla, India. The goal was to talk about Tibet's future. Representatives from Britain, China, and Tibet attended.

Britain's main representative was Sir Henry McMahon. China was represented by Ivan Chen. Tibet's representative was Paljor Dorje Shatra, also known as "Lonchen Shatra". He was a top minister in Tibet.

The British and Chinese representatives could talk to their home governments by telegraph. But the Tibetan representative only had slower land communications. McMahon had help from two officers, Charles Bell and Archibald Rose. They talked separately with the Tibetan and Chinese representatives.

Meeting Locations and Schedule

The Simla Conference was held in both Simla and Delhi. Simla was the summer headquarters for the Indian government. Delhi was the headquarters during other times of the year.

The conference had eight official meetings:

- The first two meetings were in Simla in late 1913.

- The next three meetings were in Delhi in early 1914.

- The last three meetings were back in Simla in April and July 1914.

Between these official meetings, Bell and Rose held many private talks with the participants. There were also some unofficial meetings with all three sides.

A first draft of the agreement, with a map, was approved by all three on April 27. But China's government immediately rejected it. A slightly changed agreement was signed on July 3 by Britain and Tibet, but not by China. The conference left the door open for China to join later.

Early Discussions and Border Claims

At the first meeting, Lonchen Shatra from Tibet spoke first. He said that Tibet and China had never been under each other's rule. He declared that Tibet was an independent country. He also listed Tibet's borders and demanded that China return money collected from Tibetan areas.

Ivan Chen from China then gave his side. He claimed that Tibet was a "part of China". He said that Britain or Tibet trying to change this would not be allowed. However, China promised not to turn Tibet into a Chinese province. China also wanted to have a representative in Lhasa. Chen also showed a map with China's idea of the border.

At the second meeting, McMahon said the most important thing was to define Tibet's borders. Lonchen Shatra agreed. But Ivan Chen said that deciding Tibet's political status should come first. Chen had "definite orders" from his government to focus on political questions. McMahon then said he would discuss borders only with Lonchen Shatra until Chen got permission to join. After five days, China allowed Chen to join the border talks.

Talking About Borders

Informal talks happened in December 1913. Ivan Chen admitted that the border issue was new to him. Chen claimed that China had control far into western Tibet. This included many areas like Pomed, Zayul, and Markam.

Lonchen Shatra replied that Tibet had always been independent. He mentioned old treaties and border markers. He also showed many records of taxes and administration for areas up to Tachienlu (Kangding). China did not have similar records.

McMahon then came up with the idea of "Inner Tibet" and "Outer Tibet". He saw that China had soldiers in border areas. But China had not really changed how Tibet managed its people there. So, he thought a shared presence in these areas would work. These areas would be "Inner Tibet". "Outer Tibet" would be Lhasa's main territory, with only China's special influence over it.

McMahon's Ideas and Challenges

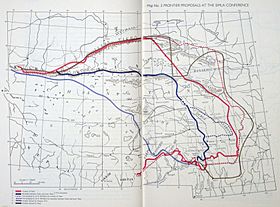

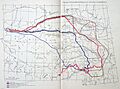

On February 17, 1914, McMahon presented his idea of "Inner Tibet" and "Outer Tibet". He showed a map with the proposed borders. He explained that old records showed Tibet's historical borders. He also said that in the 1700s, China gained some control over parts of Tibet. This created a clear line between areas where China sometimes stepped in and areas where Tibet was mostly independent. These two lines defined "Inner Tibet" and "Outer Tibet".

Both the Tibetan and Chinese representatives reacted strongly. Lonchen Shatra argued that Batang and Litang should be in "Outer Tibet". Ivan Chen claimed that China had taken back the "Inner Tibet" areas. He said his government could not change its claims.

McMahon warned China that its "uncompromising position" and fighting on the border were making it hard for him to get Tibet to agree to anything.

On March 11, McMahon presented a draft of the agreement. He asked both sides to compromise. But China was not ready. Chen said it was too early to discuss a draft. China's appointed representative for Lhasa, who was in Calcutta, advised his government to keep up military pressure. He believed Britain would not intervene with force.

The talks continued with little progress. On April 22, Chen presented five new demands. Lonchen also disagreed because Derge and Nyarong were placed in Inner Tibet. McMahon then pretended to withdraw the entire draft agreement. This made both sides rethink. Chen asked for more time to talk to his government.

After five days, the conference met again on April 27, 1914. The draft agreement, with the map, was finally approved by all three representatives. Ivan Chen approved it, but only after being told that it was not a final acceptance.

After April 1914

Between April and July, Britain talked with Russia about the draft agreement. They had to do this because of a 1907 agreement. In that agreement, Britain and Russia had agreed to keep Tibet a neutral zone.

China later said that Ivan Chen's approval of the draft agreement was not allowed. China also suggested that Chen was forced to approve it. Britain denied this. China also said that Henry McMahon was "unfriendly" to China. China asked to continue talks in London or Beijing. However, Britain supported McMahon. They said he had given China "every point" that did not harm Tibet. China kept trying to change the border through its envoys. But Britain refused. China's final message seemed to say it would not sign the convention.

The Convention Details

The border between Tibet and British India, known as the McMahon Line, was part of the map in the treaty. This border was agreed upon by the British and Tibetan representatives alone. The Chinese representative was not present for this specific negotiation.

The border they decided on was included in the Simla conference map. This map showed Tibet's boundary as a "red line" and the border between Outer and Inner Tibet as a "blue line". This map was attached to the proposed agreement. All three representatives approved it on April 27, 1914.

The agreement also had other notes. For example, it stated that "Tibet forms part of Chinese territory". It also said that after Tibet chose a new Dalai Lama, China would be told. The Chinese representative in Lhasa would then give the Dalai Lama his official titles. The Tibetan government would appoint all officers for "Outer Tibet". Also, "Outer Tibet" would not have representatives in the Chinese Parliament.

Negotiations failed because China and Tibet could not agree on the border between them. Ivan Chen, the Chinese representative, approved the treaty, waiting for his government's final word. But his government then told him to reject his approval. On July 3, 1914, the British and Tibetan representatives signed the Convention without China's signature. They also signed another agreement. This agreement said the convention would apply to them. It also said China would not get any benefits until it signed.

Ivan Chen briefly left the room when Britain and Tibet signed the documents. He did not know what was happening. He thought the main Convention was signed (but it was only approved). McMahon let him keep that idea.

Britain and Lonchen Shatra also signed new trade rules. These replaced the old ones from 1908. Evidence shows that Ivan Chen thought the Convention was a good deal. He believed it was the best they could get. He also tried hard to convince China's President Yuan Shikai to accept it.

What Happened Next

The official record of treaties, A Collection of Treaties by C.U. Aitchison, said that no final agreement was reached at Simla. However, legal experts say a treaty only becomes invalid if one party rejects it. Neither Tibet nor Britain did this.

Britain's Policy Change in 2008

Until 2008, the British government believed that China had "suzerainty" over Tibet. This meant China had a special influence but not full control. Britain was the only country still holding this view.

On October 29, 2008, Britain changed its policy. It now recognizes China's full control over Tibet. The Economist magazine reported that British officials said this means "Tibet is part of China. Full stop."

The British government sees this as an update to its position. But some people view it as a big change. Some believe this decision has wider effects. For example, India's claim to some of its northern territories is based on the same Simla Convention agreements. Some people think Britain changed its stance to get more help from China for the International Monetary Fund.

Images for kids

See also

- Treaty of Kyakhta (1915)

- Imperialism in Asia