Skeleton Army facts for kids

The Skeleton Army was a group, mostly in Southern England, that disagreed with and tried to stop The Salvation Army's marches against alcohol in the late 1800s. There were many clashes between the two groups, and some people were injured.

Contents

How the Skeleton Army Started

The first time anyone mentioned an organized group against The Salvation Army was in August 1880. This group, called The Unconverted Salvation Army, started in Whitechapel. They had their own flag and motto: "Be just and fear not."

By 1881, groups called Skeleton Armies began in places like Whitechapel, Exeter, and Weston-super-Mare. The name quickly spread to other parts of southern England. There are no records of these groups being active north of London. Most members were from the working class.

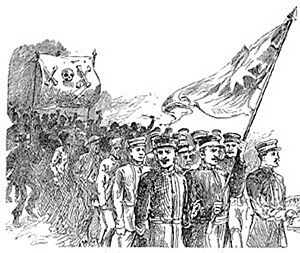

The "Skeletons" had special signs to show who they were. They used flags with skulls and crossbones. Sometimes their flags had two coffins and phrases like "Blood and Thunder." This phrase made fun of the Salvation Army's own saying, "Blood and Fire." They also used "Beef," "Beer," and "Bacca" to mock the Salvation Army's "Soup," "Soap," and "Salvation." Their flags also showed pictures of monkeys, rats, and the devil.

The Skeletons also printed their own newspapers, which were often rude and disrespectful. They used different ways to interrupt Salvation Army meetings and marches. These included throwing rocks and dead rats. They would also march while playing loud music or shouting. Sometimes, they would even physically attack Salvation Army members during their events.

Major Clashes

Although some thought the Skeleton Army started in Weston-super-Mare in 1881, news reports show it first appeared in Exeter in October 1881. In Weston-super-Mare, in March 1882, three Salvation Army members were sent to prison. This happened because they broke a local rule against public marches.

This led to an important court case called Beatty v Gillbanks (1882). The court decided that the Salvation Army was acting within the law when they marched. Even if their marches caused trouble, their main goal was peaceful. The court found that the Skeleton Army and other groups were the ones causing the riots. The prison sentences for the Salvation Army members were later canceled.

A newspaper called The Times reported on this court case. During the appeal, it was wrongly stated that the Skeleton Army began in Weston-super-Mare.

In November 1882, there was an attack in Bethnal Green. The Bethnal Green Eastern Post newspaper described it: "A real crowd of rough people has been bothering the area for weeks. These wanderers call themselves the 'Skeleton Army'.... The 'skeletons' have people who collect money for them. I found that owners of pubs, beer sellers, and butchers were giving money to this group... The collector told me that the Skeleton Army wanted to stop the Salvationists. They would follow them everywhere, beat a drum, and make fun of their songs. This made it impossible for the Salvation Army to hold their marches and services... Many of the Skeleton crowd are the laziest and worst people London has... They are like the disrespectful pub owners who dislike education and temperance. They see their business ending and are ready for anything."

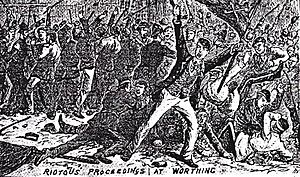

Both news reports agreed that Salvationists were hit with things. In Bethnal Green, people threw flour, rotten eggs, stones, and bricks. Many Salvationists were pushed around and beaten. When news of the trouble in London spread, Skeleton riots happened in other parts of Britain.

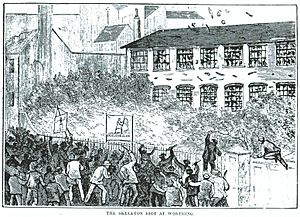

For example, in April 1884, a shop owner in Worthing who sold alcohol was upset by the Salvation Army. About 4,000 "Skeletons" joined together in Worthing to oppose the Salvationists. They painted black, sticky tar on a wall near the Salvation Army building. This ruined Salvation Army uniforms as they marched. They also threw eggs filled with blue paint at the "Sally Army." Many people in Worthing approved of these actions. However, the Salvation Army continued their work without stopping.

Captain Ada Smith led the Salvationists who faced the "Skeletons" in Worthing. General Booth, the leader of the Salvation Army, asked the police for protection in Worthing. He told Captain Smith and her group to stay in their building until they got help. But the government official, Sir William Harcourt, said he could not offer such protection. Finally, General Booth told Captain Smith and her group to march on Sundays without police protection.

On Sunday, August 17, 1884, the police, the Salvation Army, and the Skeletons met in Worthing. For an hour, the police kept things peaceful. Then the Skeletons started a riot. The area was full of screaming people, brick dust, and broken glass. The Salvationists went back to their building, and the Skeletons tried to burn it down. The building's owner, George Head, who supported the Salvation Army, defended his property and the people inside with a gun. He injured several Skeletons. Head was later brought to court for hurting a young man named Olliver.

At first, the police in London were not very helpful. The police chief, Sir Edmund Henderson, denied what was happening. But the public eventually demanded action, and the Skeleton riots in London were finally stopped.

The End of the Skeleton Army

Skeleton riots continued in other places until 1893, when they slowly disappeared. In 1889, at least 669 Salvation Army members were attacked, including 251 women. In one incident, while defending themselves, 86 Salvation Army members were arrested and put in prison for causing trouble.

When a new Salvation Army group started in Potton in Bedfordshire on June 1, 1890, many members of the Skeleton Army made fun of the local Salvationists. The War Cry newspaper reported: "...the skeletons did all the shouting and we had only the chance to bless them by showing calm love in response to the disturbance... The skeleton flag was out with its coffin, skull, and cross-bones. The whole Skeleton group was there, in uniform, beating a drum, playing flutes, spinning rattles, and screaming through trumpets. One of their chosen leaders was carried on shoulders, ringing a bell and wearing a strange hat. I noticed that the pub owners looked happy to see this group and several waved their hats. But we were good friends with the skeletons; twelve of them even sat at our tea table... Their leaders were very polite and truly wanted to keep their somewhat wild followers in line. They were almost completely obeyed. Their skeleton War Cry newspaper was sold freely, but it wasn't as good as the original."

Major Nigel Bovey, in his book 'Blood on the Flag', says there is no clear proof that a Salvationist was killed directly by a Skeleton Army member. He notes that Captain Sarah Jane Broadhurst was hit during an attack by the Skeletons in Shoreham in 1884. She died eight years later in 1892.

The mayor of Eastbourne once said he would "stop this Salvation Army business" with help from the Skeleton Army if needed. Skeletons attacked many Salvationists. Salvationists believed it was against their Christian beliefs to defend themselves. They thought the police should protect them instead.

From Skeleton to Salvationist

Charles Jeffries was a leader in the Skeleton Army in Whitechapel in 1881. He was known for stopping Salvation Army public meetings and sometimes attacking Salvation Army Soldiers and Officers.

Later, Jeffries changed his mind and started going to a Salvation Army corps. He soon became an active Soldier. After training, he became an Officer. He worked in many countries, including China and Australia. He eventually rose to a high rank, becoming a Commissioner. In the 1930s, he was in charge of all Salvation Army groups in Britain.

In 2019, a musical was written about Charles Jeffries' amazing change.

|

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |