Sleeping Sickness Commission facts for kids

The Sleeping Sickness Commission was a special group of doctors and scientists. The British Royal Society created it to study a serious disease called African sleeping sickness. This disease, also known as African trypanosomiasis, was spreading fast in Africa around the year 1900.

The outbreak started in 1900 in Uganda, which was then a country protected by the British Empire. The first team in 1902 included Aldo Castellani and George Carmichael Low from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. It also had Cuthbert Christy, a doctor working in India. From 1903, David Bruce from the Royal Army Medical Corps and David Nunes Nabarro from the University College Hospital took over. The commission found out that a tiny germ in the blood, called Trypanosoma brucei, caused sleeping sickness. This germ was named after David Bruce.

Contents

How It Started

Signs of sleeping sickness in animals were written about in ancient Egyptian times. Old records from Arabian traders also mentioned that many people and dogs in Africa had sleeping sickness. It was even said that Sultan Mari Jata, an emperor of Mali, died from it.

In the 1800s, it was still a major disease in southern and eastern Africa. It was a constant threat to cows and horses in places like the Zulu Kingdom. The Zulu people called this animal disease nagana, which means "to be sad or low in spirit." This name became very common in Africa. Some Europeans called it the "fly disease."

The first time human sleeping sickness was described by a doctor was in 1734. An English navy surgeon named John Aktins wrote about the brain and nerve problems that happened in the late stages of the infection. He called the cause of death "sleepy distemper." In 1803, another English doctor, Thomas Winterbottom, described more symptoms. He noted that swollen lymph nodes in the neck were a key sign, even early on. Slaves with these swellings were not allowed to be traded. This symptom is now called "Winterbottom's sign."

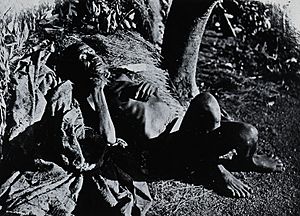

From 1900, a big outbreak of human sleeping sickness happened in Uganda for about 20 years. It began in the Busoga kingdom in eastern Uganda. The first human case was recorded in 1898. It was very bad in 1901, with about 20,000 deaths. More than 250,000 people died in this widespread sickness. At that time, the disease was known as the "negro lethargy."

Early Discoveries

How the Disease Spreads

Scottish missionary and explorer David Livingstone was the first to guess that sleeping sickness in animals was spread by the bite of the tsetse fly. In his report from 1852, he wrote that his cattle got sleeping sickness after being bitten by tsetse flies. This happened in valleys near the Limpopo River and Zambezi River, and by Lake Malawi and Lake Tanganyika.

He did an experiment with cattle bitten by tsetse flies. In his 1857 report, he said:

The animal keeps eating, but gets very thin. Its muscles become weak and floppy. This continues until, maybe months later, it gets diarrhea. The animal can no longer eat and dies from being extremely tired. Animals that are in good shape often die soon after the bite, staggering and becoming blind, as if their brain is affected... These signs seem to point to a poison in the blood. A tiny germ enters when the fly's mouth part goes in to get blood. This poison-germ, found in a small sac at the base of the fly's mouth, seems to be able to make more of itself. After death from a tsetse bite, there is very little blood, and it hardly stains the hands when examining the body.

Livingstone also tried to cure infected horses using arsenic. He wrote about this in The British Medical Journal in 1858.

Animal Sleeping Sickness Germ

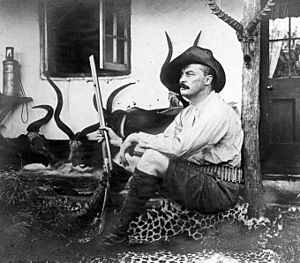

Scottish doctor David Bruce was working for the Royal Army Medical Corps in South Africa. He was asked to study "nagana," which was making many cattle and horses sick in Zululand. On October 27, 1894, he and his wife Mary Elizabeth Bruce, who was also a scientist, moved to Ubombo Hill. This was where the disease was most common.

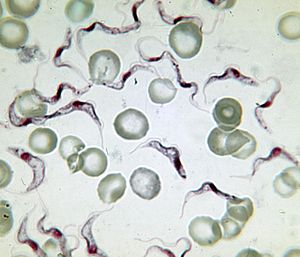

He found tiny living things, called protozoan parasites, in the blood of sick animals. This was the discovery of Trypanosoma brucei. This name was given by Henry George Plimmer and John Rose Bradford in 1899 to honor Bruce. The group of germs called Trypanosoma was first named by Hungarian doctor David Gruby in 1843. He found T. sanguinis in the blood of frogs. At this time, no one knew how the infection spread in animals or if it was related to human sleeping sickness.

The First Human Germ

On May 10, 1901, an English steamboat captain went to a hospital in Gambia with a high fever. British Colonial Surgeon Robert Michael Forde looked at his blood. He saw some tiny moving things that he thought were parasitic worms. He wrote about what he saw in 1902.

The same person came back to the hospital in December 1901 after getting better. Forde asked Joseph Everett Dutton, a scientist who studied parasites and was visiting the hospital. Forde told Dutton that he had seen "many very active worm-like bodies whose nature he could not figure out." Dutton made slides of the blood. He decided that the tiny things were protozoans from the Trypanosoma group. But they looked different from other known species and caused a different disease. In his 1902 report, he suggested:

Right now, it's impossible to say exactly what species it is. But if further study shows it's different from other disease-causing trypanosomes, I suggest it be called Trypanosoma gambiense.

The Commission

The serious problem of the Uganda outbreak was discussed by the Royal Society in 1902. At that time, people around the world were debating what caused sleeping sickness. Many thought it spread easily from person to person because it was moving so fast. The Royal Society's Malaria Committee was put in charge of planning the investigation.

Patrick Manson suggested that the best people for the job were Aldo Castellani and George Carmichael Low. Both were from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and had been Manson's students. He also suggested Cuthbert Christy, a doctor working in India. The Royal Society formed the three-person Sleeping Sickness Commission on May 10, 1902.

The First Commission

Low was chosen to lead the first Commission. His job was to look for Filaria perstans, a small roundworm carried by flies, as a possible cause of sleeping sickness. Low had found in 1901 that another roundworm, Filaria bancrofti, caused elephantiasis in humans. Since Manson's discovery in 1878 that F. bancrofti was carried by mosquitoes, people thought roundworms and mosquitoes might be linked to sleeping sickness. This was why the Royal Society put the problem under its Malaria Committee.

Castellani was told to look for a bacterium, Streptococcus, as another possible cause. Christy was to study how the disease was spreading.

The team arrived in Entebbe, Uganda, and set up a lab there in July 1902. The lab was first planned for Jinja, which was closer to where the outbreak started. But Entebbe was chosen for easier management and because roundworms had been reported there. There were disagreements among the team members. Christy, who felt he had a small role, spent his time hiking and hunting. The team was described as a "badly matched group" and a "strange bunch," and their trip was called "a failure." Low, who was described as "stubborn and easily offended," soon became sad when he found that roundworms were not common in people with sleeping sickness. He left Africa in October 1902 and never came back.

The Second Commission

In 1901, the Portuguese government sent their own Sleeping Sickness Commission to Angola. By 1902, they said they had found bacteria (Streptococcus) in many cases of sleeping sickness. This made Castellani feel good about his own research. Soon, he also claimed to have found the bacterial infection. He sent a first report called "The cause of sleeping sickness (Preliminary note)" to the Royal Society on October 14, 1902. It was published in The Lancet in March 1903. He wrote that he had "good reason to believe [the bacterium] was the cause of sleeping sickness."

The Royal Society was not sure about Castellani's report. So, they formed a second Commission in early 1903 to find the truth. David Nunes Nabarro from the University College Hospital was named "Head of the Commission" on January 5. But Nabarro worried he wasn't senior enough. He asked the Royal Society to choose someone else as head. At the Royal Society's request, the British War Office appointed David Bruce from the Royal Army Medical Corps as the team leader in February. Bruce and Nabarro joined Castellani and Christy on March 16. The Commission finished its work in August when Bruce left Africa after a successful investigation.

The Third Commission

The third Commission worked between 1908 and 1912. It was led by Bruce and included Albert Ernest Hamerton, H.R. Bateman, and Frederick Percival Mackie. By this time, the German government had a similar commission led by Robert Koch to study the outbreak in East Africa. Koch's helper, Friedrich Karl Kleine, found that tsetse flies carried the tiny protozoan germ. Bruce's Commission confirmed that the infection was spread by the tsetse fly, Glossina palpalis. They also figured out how the germ developed inside the tsetse fly.

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |